By late last week, the fight between the Bush White House and Congress over the firings of nine U.S. attorneys seemed to be leading toward possible contempt charges for some former administration officials. The Bush administration had previously asserted executive privilege over certain documents and witnesses sought by Congress in its investigation of the firings, even directing former White House counsel Harriet Miers to disobey a subpoena ordering her to appear before Congress. Democratic legislators were left with the option of certifying a citation of contempt of Congress to the U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia in hopes of compelling Miers and former White House political director Sara Taylor to testify fully.

On July 19, however, the Washington Post revealed that the Bush administration was unafraid of contempt citations. Should Congress certify a contempt citation to U.S. attorney Jeffrey Taylor's office, it would be Taylor's duty under federal law to bring the matter before a grand jury -- but the White House will direct him not to.

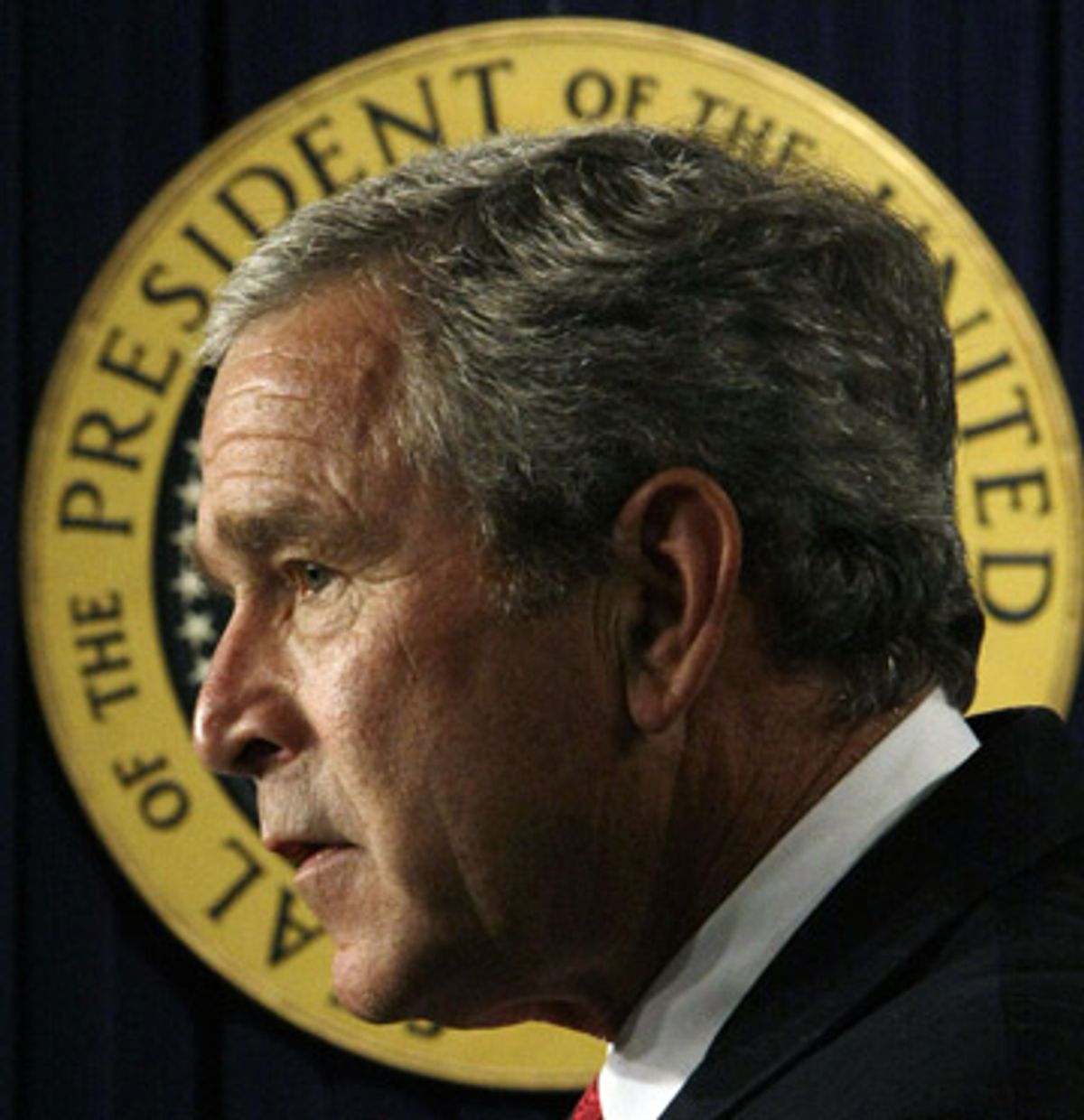

Reaction from some corners was swift, severe and horrified. President Bush seemed to many to be enlarging an already expansive definition of executive privilege. Karen Tumulty, Time magazine's national political correspondent, said that with the Post article "the phrase [contempt of Congress] takes on new meaning ... There's no way to challenge the President's assertion of executive privilege, because, well, the President has asserted executive privilege." And in a statement given to Salon, Senate Judiciary Committee chairman Pat Leahy, D-Vt., called the decision "deeply disturbing" and said that "this President and Vice President seek to override the independence of law enforcement and manipulate our valued system of checks and balances. This is another demonstration of the lawless and unchecked path the President, the Vice President and their loyal aides have taken us down."

All that may well be true. And it may be especially disturbing to some that the Bush administration's position seems to flow from the radical "unitary executive" theory, which exalts the power of the presidency over the other branches of government and has played a role in many controversial administration decisions. But if the White House's justification for its refusal to honor any congressional contempt citations is examined strictly on legal grounds, then in this case it is not appropriating to itself any novel idea of presidential power. The move itself was predictable, based on positions held for more than two decades during four different presidential administrations by the Department of Justice's Office of Legal Counsel. In fact, though the Clinton administration never faced a similar showdown in its own executive privilege fights with Congress, it would almost certainly have taken a similar position in such a case. When contacted by Salon, even those legal scholars who served under Democratic administrations said that whatever their opinions about President Bush's prior assertions of privilege or of his order to Miers not to appear before Congress, they think the White House is correct -- or at least on legally defensible ground -- in this latest assertion of power. Congress may simply have to think of new ways to push back.

"I'm struggling here," Cass Sunstein, a professor at the University of Chicago's Law School (he wrote "Radicals in Robes: Why Extreme Right-Wing Courts Are Wrong for America" and spent some time in the OLC under both the Carter and the Reagan administrations), said in an interview, "because I don't have the reaction that the president's assertion of power to stop the U.S. attorney from prosecuting is independently outrageous ... This is the attorney general saying to the U.S. attorney, 'We don't want you bringing a prosecution which is violative of the president's constitutional prerogatives. You work for the guy, so don't do that.' That's, in the abstract, OK. In the particular case it's not OK, where it's being invoked to say that Ms. Miers can refuse to even appear before a congressional committee. That's the most outrageous part of this."

Dawn Johnsen, a professor at the Indiana University School of Law who served in the OLC for five years during the Clinton administration, heading it as acting assistant attorney general from 1997 to 1998 (and who has previously written for Salon), took a similar stance.

"I think that the position that the administration is taking here is very strong, actually. I'm someone who thinks that the Bush administration's assertion of executive privilege is overbroad and that they should be turning over more information, but I think that it's right that if the president does legitimately assert executive privilege the president may direct the U.S. attorney not to prosecute someone who acts consistently with that assertion."

It may be surprising to hear Democrats expressing such views, even with caveats, but opinions on this narrow subject are often based as much on loyalty to a branch of government as on allegiance to a political party. The argument may not be about a "rogue presidency," but about the relative powers of the executive and legislative branches of government.

The current position taken by those who side with the executive stems in part from a 1984 opinion written by Theodore Olson, who headed the OLC between 1981 and 1984 under Ronald Reagan. Later, he would successfully argue Bush v. Gore, the Supreme Court case that decided the 2000 presidential election for George W. Bush, and then serve the Bush administration as solicitor general from 2001 to 2004. The relevant statute says that when Congress prepares a citation for contempt of Congress, it should pass that citation to the U.S. attorney, "whose duty it shall be to bring the matter before the grand jury for its action." But in the 1984 opinion, Olson, who was traveling and unavailable for comment on this story, disagreed with the plain language of the statute.

A "United States Attorney is not required to refer a congressional contempt citation to a grand jury or otherwise to prosecute an Executive Branch official who carries out the President's instruction to invoke the President's claim of executive privilege before a committee of Congress," Olson wrote. "Neither the Judicial nor Legislative Branches may [direct] the Executive Branch to prosecute particular individuals."

OLC opinions do not have the force of law, but they are generally treated as precedent within the Justice Department, and Olson's opinion is no different. The Clinton administration may never have had to rely on its ultimate conclusion, but neither did the administration repudiate Olson's opinion -- indeed, the Clinton administration cited it at least twice.

"I cannot recall that we ever had to take the position on this exact issue, involving an actual potential contempt citation, when I was [in the OLC]," Johnsen says, but "we did look at the '84 opinion and generally cited it favorably."

Marty Lederman, a professor at the Georgetown University Law Center who also served in the Clinton-era OLC and whose posts on the blog Balkinization generally express positions critical of the Bush administration, is critical of Olson's opinion. He has previously written that "there are many things about the 1984 OLC Opinion that strike me as wrong or overstated," and has called its conclusion "contestable ... a tricky question."

Told by e-mail of what Johnsen and Sunstein had said, though, even Lederman said there may be some truth to the Bush administration's argument. "As the statute now stands, Dawn and Cass are probably correct -- but [Morrison v. Olson, a 1988 Supreme Court decision] makes it much more complicated," Lederman said.

Reflecting where the divide over this question really lies, Democratic veterans of the legislative branch took an unequivocal stance against the president's assertion of power.

One former Democratic congressional staffer who asked not to be named noted that the law the president is flouting contains very specific and unusual language about a federal prosecutor's obligation to proceed with congressional contempt citations. According to the staffer, federal laws dictate that a prosecutor "shall" bring a case in very few instances; in an instance like this one, where Congress went out of its way to include such language in the statute, it should be interpreted with that in mind.

"If you kill somebody, there's nothing that says a prosecutor 'shall' present the case to a grand jury," the staffer said. "It's very unusual to tell a prosecutor they have to do something."

Charles Tiefer, a professor at the University of Baltimore School of Law who served as solicitor and deputy general counsel of the House of Representatives from 1984 to 1995 (and who has previously written for Salon), agreed.

"People know what 'shall' means," Tiefer argued. "The attorney general can no more tell the U.S. attorney to disregard the certification than he can tell the U.S. attorney to go up to Capitol Hill with a machine gun and start shooting."

Tiefer described Olson's 1984 opinion as "sour grapes" by an administration that had just conceded to Congress a fight that involved these issues the year before. Democrats who served in the OLC agree with Olson, according to Tiefer, because executive branch officials stick together in fights with the legislative branch.

"I don't know anyone in history -- until Ted Olson came along -- who for a second bought this nonsense, and I take that quite seriously," Tiefer said. "I'm sure the people who were in OLC love it; I know they love it ... OLC people always sing harmony and melody with OLC, regardless of whether they're in a Democratic or Republican administration. They think, 'Oh, God, we don't want [former Attorney General] Janet Reno to have to appear before [Indiana Republican Congressman] Dan Burton, so rah-rah-rah, sis-boom-bah, we stand with Ted Olson.'"

The tug-of-war between the executive and the legislative branches over this issue is ongoing because there has been no definitive legal decision to resolve it. Both sides are traditionally loath to bring executive privilege fights to the courts for fear that they will lose, thereby setting a precedent that cuts against them. The courts, meanwhile, are reluctant to take executive privilege cases; the judicial branch's general policy is to encourage the legislative and executive branches to negotiate and renegotiate. Only when there's no room for accommodation will the judiciary intervene. Just one standoff similar to the current situation has ever made it to court, in fact.

In November 1982, a subcommittee of the House of Representatives delivered a subpoena to Anne Gorsuch (sometimes known by her second married name, Burford), then the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, asking her to produce certain documents. The Reagan administration asserted executive privilege over the documents and directed Gorsuch not to produce them, so on Dec. 16, 1982, the House cited Gorsuch for contempt. Even before the House could certify the citation to then U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia Stanley Harris, the Justice Department sued the House, seeking an injunction against the citation. As U.S. attorney, by law, Harris became a party to the lawsuit. And so -- different from the current administration's policy -- Harris decided on his own not to proceed with the contempt charges until the civil suit had concluded. In a 1996 interview for an oral history project conducted by the Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit, Harris, by then a U.S. district judge, explained:

"It occurred to me that what was important for me as the person charged with the responsibility for prosecuting her was that at the end of the line nobody could say that I had been told what to do or what not to do. And I came in the first morning after receiving the contempt citation and called Main Justice and said, 'I want to make it clear that I am not going to talk to anybody at Main Justice about this case.'"

The Reagan administration's lawsuit was dismissed before any of the claims made by the current administration could be put to a real test. In his opinion dismissing the case, Judge John Lewis Smith Jr. said, "The two branches [should] settle their differences without further judicial involvement," which is eventually what happened -- the Reagan administration turned over the documents sought by the House.

A quarter century later, another administration has decided to do battle. But if Congress backs down on its contempt threat without fighting, or fights the Bush administration and loses, it still has two options left to compel full testimony from Harriet Miers and Sara Taylor. It can pursue civil contempt proceedings in court, or it can attempt to use its own "inherent contempt" power to arrest and detain Miers or anyone else who has failed to comply with a subpoena, and then hold its own trial. Congress could hold any persons thus detained until they complied or until the end of the session of Congress, whichever came first. It has not used that power since 1934.

But some proponents of congressional power argue that all these remedies come with their own problems, leaving Congress at a disadvantage in fights with the executive. In an article for Roll Call that ran just a day before the Post's July 19 story, Paul M. Thompson, who was an assistant U.S. attorney from 2002 to 2005 and then served as counsel to former Sen. Mike DeWine, R-Ohio, on the Senate Judiciary Committee, argued that Congress needs to give itself new powers for its fights with the executive branch.

"The process we have right now when Congress gets into a dispute with the executive is like the New York Yankees playing a Little League baseball team," Thompson said in an interview. "The executive is the Yankees, Congress is the Little League team, and there is absolutely nobody to be the umpire."

Thompson said he tends to believe that the executive branch has the power it asserted last week, but thinks that's beside the point. What Thompson wants to see is a change in the law, so that Congress has powers like, for example, the federal courts or the secretary of agriculture, both of whom can pursue contempt charges essentially on their own.

"The way the system is set up institutionally, [Congress] can never get a resolution on these matters," Thompson said. "It's almost a beat-the-clock situation for the president ... We need -- and I don't have any clear answers yet -- we need to figure out a process that works better than the one that's in place."

Sen. Leahy might agree. (He was traveling and unavailable for comment beyond the statement referenced earlier in this article.) In 2000 he used the apparent weakness of Congress' position to argue against Congress' citing a White House official for contempt. But at that time, Republicans controlled Congress and the official was a Democrat -- Attorney General Janet Reno. Dismissing the efficacy of both the criminal and the civil contempt procedures, Leahy said Congress' only option was to use its inherent contempt power -- and he dismissed that as well, calling it "an embarrassing spectacle."

"The only way to enforce a contempt citation is by a trial on the Senate floor ... The civil contempt mechanism normally available to Congress ... specifically exempts subpoenas to the executive branch," Leahy said. "Obviously, there is also a criminal contempt citation ... but this procedure requires a referral to the Justice Department. Is [Sen. Arlen Specter, R-Pa., then the chairman of the Judiciary Committee] suggesting that we make a criminal referral of contempt about the Justice Department to the Justice Department? I assume not."

Shares