In the corner of a hotel conference room, the Republican youth circled their chairs, crumpling neatly pressed suits and skirts to hear the influential Utah Sen. Bob Bennett explain the magical key to winning the 2008 Republican presidential nomination. "Up and down, there is only one message that cuts it," the gray-haired senator told the crowd of College Republicans during their convention in late July. "That message is, 'I can beat Hillary Clinton. '"

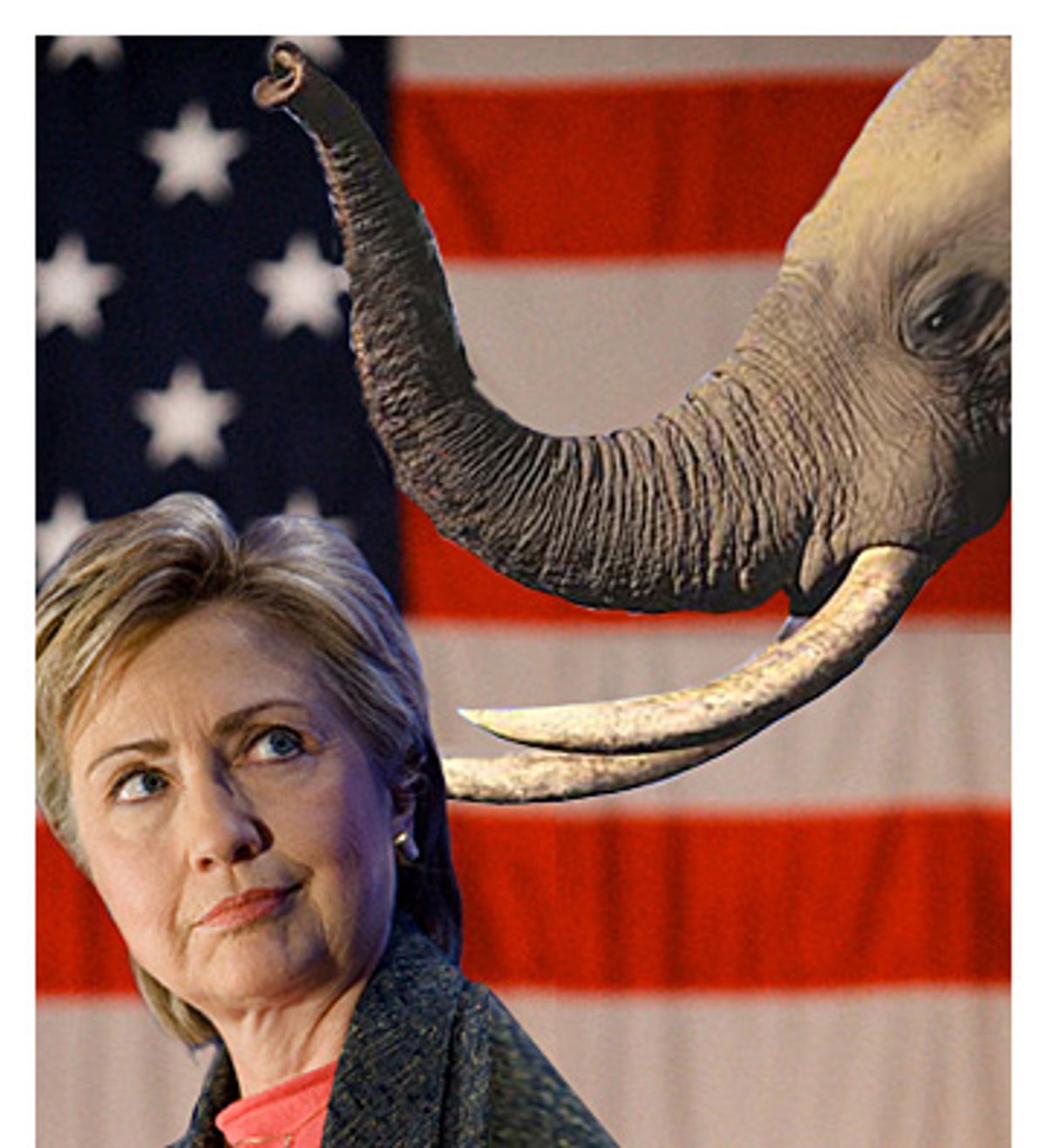

He was speaking without a microphone, but no one mistook his words. Over the last year, as Republicans have sought out their next standard bearer, no candidate has excited their passions and united their focus more than the Democratic senator from New York. Clinton is regularly evoked in stump speeches, presidential debates and fundraising events as a symbol for all that the Republican voters stand to lose in the coming election. She is, in many ways, the glue now keeping the Grand Old Party from further splintering into disarray after the 2006 elections.

"It unifies the party. It motivates a part of the base," explains Grover Norquist, a longtime party activist who runs the group Americans for Tax Reform. "Hillary can be scary."

As the campaign rolls into its next phase, the Republican Party is once again exploiting that fear by turning Hillary into its anti-mascot and punching bag. Last week, the Republican National Committee sent out a fundraising appeal that compared the Democratic primaries to an attempted "coronation" that would plunge the nation back into its liberal past. "The return of Hillary-Care," wrote Mike Duncan, the operational chairman of the Republican Party. "Higher taxes for all Americans to pay for her big government plans." It was a message he hoped would get Republicans, who overwhelmingly disapprove of the Clintons, writing contribution checks. "If we are to stop Bill and Hillary from returning to the White House, we must act now," the appeal urged, a full five months before the first primary ballots will be cast.

Meanwhile, Republican candidates have been furiously competing to meet Bennett's beat-Hillary standard, even though Clinton is far from a sure bet as the Democratic nominee. Last month, former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney, who now leads in many Iowa and New Hampshire polls, took a swipe at his rival Fred Thompson by suggesting that the former Tennessee senator may not have what it takes. "To beat Hillary Clinton, you're going to have to raise a lot of money. You're going to have to work like crazy," Romney told a reporter.

More recently, Romney has tried to establish himself as the front-runner by lashing out at Clinton on the stump. "I don't think Hillary Clinton could get elected president of France with her platform," he scoffed last week at a senior citizen's center in New Hampshire. Former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee, who is running far behind in the presidential field, has harped on his home-state knowledge of the Clinton family: "No one on this stage probably knows Hillary Clinton better than I do," he boasted at one of the recent Republican debates, "and I will tell you that it's probably not a good idea to put either of them back in the White House."

Sen. John McCain of Arizona has also attempted to make Clinton central to his run for president. Last year, as he sowed the early seeds of his campaign, McCain's team traveled the country for private meetings with Republican donors, touting polls showing that he was the best general election candidate to face Clinton. "He got a lot of former Bush guys who didn't like him," said a senior Republican operative, who has since signed on to a rival campaign. "They went with him not because they liked him, but because they thought he could beat Hillary."

At the College Republican convention, Bennett, who is a Romney supporter, explained the recent collapse of McCain's campaign as a result of the GOP's Clinton obsession. "John McCain's people came into Utah and they said, You may not like John McCain, indeed you may hate John McCain -- doesn't make any difference," Bennett said. "Here is a poll that shows that John McCain can beat Hillary Clinton." But Bennett said that strategy only worked until former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani arrived on the scene. "Giuliani got in, and what's the first thing that the Giuliani campaign put out? A poll that shows Giuliani beating Hillary Clinton by a bigger margin."

Indeed, Brent Seaborn, the strategy director for Giuliani, released a memo in May saying that Giuliani "may be the only Republican candidate that can compete in 2008 against the Democratic nominee." The memo noted that, at the time, Giuliani led Clinton in "every major national poll conducted by an average of 4 points." More recent national polls, though far from reliable more than 15 months before the election, show that Clinton and Giuliani are essentially tied in head-to-head matchups.

The Clinton campaign has accepted all the Republican attention as a badge of honor. "They clearly recognize that she is the strongest general election candidate on the Democratic side," gushed Phil Singer, Clinton's campaign spokesman, in an interview. "Clearly Republicans are aware of her strengths and are nervous."

The Republican focus on Clinton may say more about the Republican Party than it does about her inevitability as the Democratic nominee. Though she polls better nationally than her Democratic rivals, she currently trails slightly in most Iowa caucus polls to John Edwards, and she has been surprisingly outstripped in fundraising by Barack Obama. But this has not stopped Republicans from referring regularly to the Democratic Party as a shell organization at the beck and command of the Clinton family, even if that's a flimsy caricature at best.

Norquist, for one, insists he is confident that Clinton will come out on top. "The Clintons run the Democratic Party the way the Bhutto family runs the PPP," he said, in a reference to the corrupt and dynastic Pakistan People's Party. Republican leaders, such as former House Majority Leader Tom DeLay, long ago elevated the Clinton family to nearly mythic stature, claiming that the Clintons are backed by a vast "George Soros-funded, Harold Ickes-led shadow party." But Republicans have a history of glaring disconnection between their strategic prognostications about the Democrats and the way things actually turn out. As recently as the fall of 2003, presidential advisor Karl Rove was betting hamburgers in the White House that Howard Dean would be the Democratic nominee. A few months later, Dean's campaign deflated after the first caucus returns in Iowa.

One likely explanation for the Republican fixation on Clinton can be found in poll numbers. At several points this year, the Gallup Poll has found that more people have an unfavorable view of Clinton than a favorable view, a marked contrast to the relatively positive ratings of Obama and Edwards. These ratings, which put her unfavorables at around 48 percent, are by no means a barrier to victory next year, say pollsters. "By the time you get to the November of an election year, favorability ratings are normally in the low to mid-50s," explained Jeff Jones, the managing editor of the Gallup Poll. "I don't think she would have to make a real dramatic turnaround to win the general election."

But the numbers do demonstrate Clinton's clear appeal as a Republican boogeywoman, in much the same way that President Bush is often evoked by Democrats to rile liberal crowds. In April, only 15 percent of Republicans had a favorable view of Clinton, compared to 78 percent of Democrats and 43 percent of independents.

So the race for the ultimate Clinton-beater for the general election is destined to continue, even as her place as the Democratic nominee remains in doubt. At the College Republican convention, Bennett tried to make the case that Romney is the only man remaining who can beat Clinton. "Forget the polls. Analyze, in reality, who can really beat Hillary," he told the fresh-faced youngsters. "We want a new face. We want someone with experience. And we want someone who looks good on television. Mitt Romney is No. 1 in all three categories."

It all seemed very cut and dried. But about an hour later, Sen. Trent Lott of Mississippi came before the crowd to speak on behalf of John McCain, who recently lost most of his senior campaign staff in a major shakeup. "He is getting hammered right now," Lott acknowledged. "You know why? It's because the media thinks he is the most serious challenge to Hillary Clinton becoming president. They think if we take him out now, we won't have to deal with him next year."

Lott's message squarely addressed the twin obsessions of the Republican base. Not only did Hillary Clinton control everything, including the media, but Lott had announced the apparent discovery of yet another Republican candidate who could finally take her down.

Shares