Ronald Lewis, a retired streetcar-track repairman with a homemade culture museum in the backyard of his restored Lower Ninth Ward house, doesn't think much about anniversaries. "But if it helps people understand my life and the lives of other people here in New Orleans," he said on Sunday, "if it makes them think about why we're here and we won't leave, let 'em have an anniversary."

There are fewer media folk in New Orleans gearing up for Wednesday's second anniversary of Hurricane Katrina than were here for last year's commemoration. Maybe that's a good thing -- the first time around most locals seemed genuinely annoyed by the drop-in presence of so many cameras and commentators, many of whom knew little of the city and craved simply a good setup shot and a ticket out of town. ("Get me some blight," they might as well have said at last year's media center, and very nearly did, "and a black man with a trumpet.") I remember one Ninth Ward family who stood by and watched as an anchorwoman held her microphone in front of their devastated home: "The producer said he doesn't want us in the picture," the father told me, holding his baby in his arms. This year, those disaster images now seemingly played out, maybe the coverage will get further beneath the surface, down to nuances of the issues that linger: housing, education, crime, federal and state aid, and culture.

But those who live in New Orleans -- by even optimistic estimates, around 60 percent of pre-Katrina population level, or nearly 300,000 -- hardly need to mark calendars. Every day is an anniversary, a stark reminder of nature's wrath and more so of the very unnatural disasters of levee failures, insurance shortfalls, and a tide of bureaucratic red tape that rivals even the water for its ability to stall lives. Two years after the storm, only about one-third of those residents approved for their "Road Home" awards from the Louisiana Recovery Authority have received payments.

The number of press people may be down, but the politicians have been out in force this year. And there has already been much talk, a good deal of it in conferences with impressive, even hopeful, titles. At a Hope and Recovery Summit hosted by Louisiana Sen. Mary Landrieu Monday, presidential candidates took turns at public interviews with news commentator Soledad O'Brien. Democratic Sens. John Edwards and Hillary Clinton both pointed fingers of blame at the Bush administration for slow and inadequate response; each supported the idea of investing some $40 billion to $50 billion to rebuild the levees to Category 5 standards.

Edwards described the federal response to Katrina, then and now, as "a national embarrassment" and spoke of the need for "a high-level person reporting to the president every morning about what was done in New Orleans the previous day." Clinton, addressing the Kafkaesque scenarios resulting from recovery bureaucracy, said simply, "You can't make this stuff up. It's beyond satire." She presented a 10-point recovery plan that, again, began with one Cabinet-level figure in charge. Both candidates praised the efforts of private citizens as the real backbone of recovery.

Republican Rep. Lindsay Hunter took that citizen-action theme one rather disturbing step further. "Government is inept," he said. "Bureaucracies are inept. I see a great future for New Orleans based not on what government does for people but what free people do for themselves." At one point, O'Brien asked, straight-faced, "We appreciate that you appreciate that firemen and old ladies in church groups have come down here to help, but you don't think they can rebuild the levees, do you?" Moments later, discussing the problems with police protection, Hunter said frankly, "To the people of New Orleans, I have to say that's a local issue. I can't help you with that."

A day earlier, Sen. Barack Obama spoke at an early morning Sunday service at First Emanuel Baptist Church in Central City. Picking up on the fire and urgency of the Rev. Charles Joseph Southall III and his stirring choir and six-piece band, Obama matched their cadences, invoking the Sermon on the Mount, with its admonition to Christians to build on a rock of faith in order to withstand life's storms. "I know I'm not the only person that's going to be in town this week," he said in allusion to his fellow candidates, and spoke of an "empathy deficit," the need to "rebuild a trust that's been broken," and most notably and specifically, about a plan to create a funding pool from private insurers to be drawn on for catastrophic losses.

The most interesting discussions of the past week were those at Saturday morning's executive session of the World Cultural Economic Forum, hosted by Lt. Gov. Mitch Landrieu at the French Quarter's Le Petit Theater, the oldest community theater in the country. "I don't know that we did not take for granted the cultural riches we have here," Landrieu said, "until after the international community gasped when they thought about what might be lost." In fact, a focus on culture in New Orleans -- on what might be lost as well as on how culture holds important keys to many aspects of recovery, be they economic, civic or spiritual -- may prove to be the essential ingredient for productive conversations about New Orleans right now.

Erosion of our coastal wetlands may have paved the way for the natural disaster that hammered this city. But the least-mentioned aspect of the resulting devastation -- the erosion of what ethnographer Michael P. Smith once called "America's cultural wetlands" -- should be of primary concern. The resilient African-American cultural traditions of New Orleans, famously seminal to everything from jazz to rock to funk to Southern rap, also contain seeds of protest and solidarity that guard against storm surges of a man-made variety. Erasure of these wetlands exposes many to the types of ill winds that shatter souls.

Landrieu's forum gathered wisdom from many local and national experts on cultural programming, funding and studies, and it attracted officials from some 20 foreign nations. At one point, Denis G. Antoine, ambassador to the U.S. from Grenada, said, "If we're taking about rebuilding New Orleans, we have to ask: Which New Orleans are we talking about? We have to talk about social values and an ancestral past. There is an anthropological aspect to the nurturing of a new New Orleans and this will help direct what is appropriate and what is not."

One more modest example of cultural education and economy could be found Saturday afternoon at the peach-colored house of Cherice Harrison-Nelson, one in the row of new homes within the Ninth Ward Musicians' Village complex. Harrison-Nelson is the daughter of Donald Harrison Sr., a celebrated Mardi Gras Indian chief; this was a weekly session of the Guardians Institute, conceived and run by Herreast Harrison, Donald's widow, and temporarily held at Cherice's home until Herreast's is rebuilt. Herreast envisions her institute as "a safe haven for children, and a place where cultural traditions are supported and authentically transmitted." Cherice, who has worked as a teacher and a school administrator, explained, "Something deep within your soul calls you to do this. It just calls you and you've got to do it for your mental and physical survival, and for the welfare of those around you."

At her house, women sat sewing beaded patterns of eagle heads onto canvasses, practicing for the creation of Mardi Gras Day costumes. Kevin Cooley Jr., the 5-year-old chief of the Young Guardians of the Flame group, sat with a half-dozen other children and learned the bamboula and other African rhythms that had been played in Congo Square, just off Rampart Street, more than a century ago. There were discussions of tradition, book reports and finally, $25 paychecks for a performance the previous week. "If Katrina did anything good," Herreast said at one point, "it gave new meaning to all of this. And it changed our expectations: We don't want the same old thing. We want something better."

For all the talk and all the music of the past few days in New Orleans, the most emphatic statement about post-Katrina life, and particularly about cultural economy, was silence.

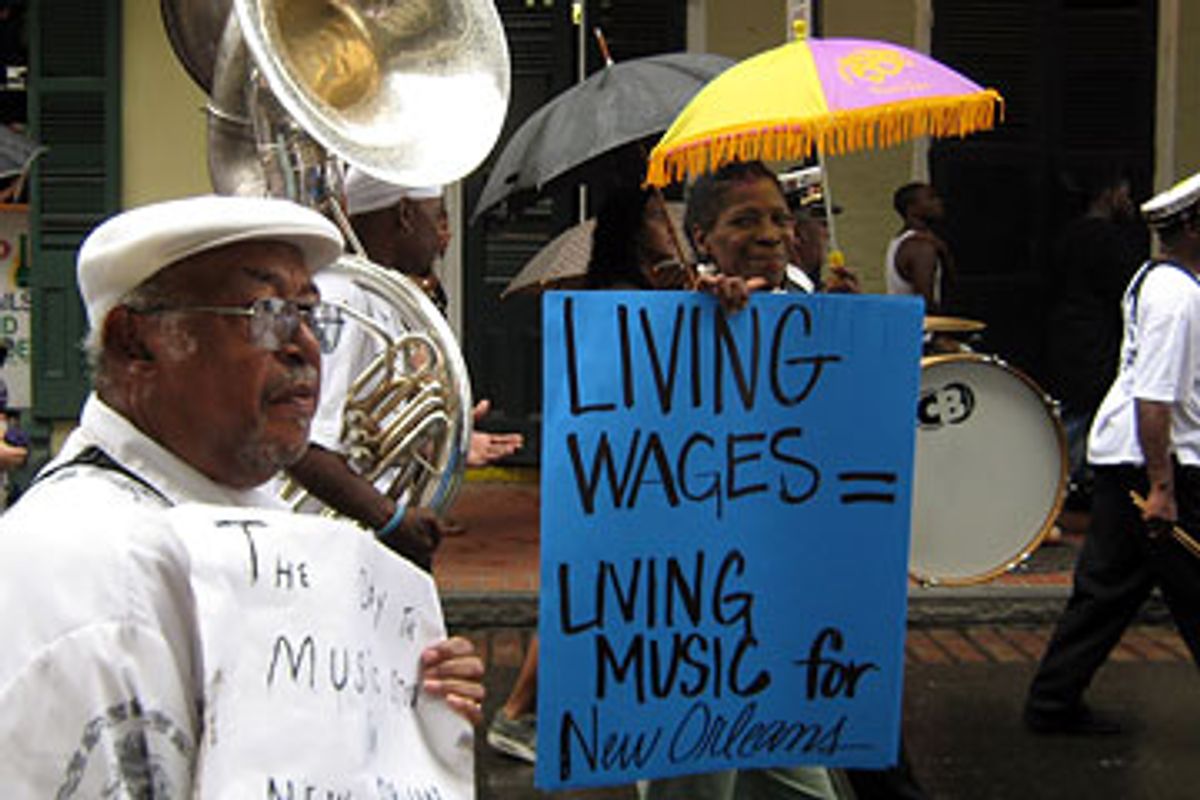

Sunday's Musicians Solidarity Second Line found members of the Treme Brass Band and some two dozen other musicians, instruments in hand, assembled for a traditional second-line parade. At a typical second-line, a brass band plays, and supporters follow along, dancing and clapping out rhythms. The events, held nearly every weekend from September through June, are powerful expressions of community and culture. Since Katrina, they have taken on deeper meaning as assertions of determination and domain. But on Sunday, not a note was played, not a step danced. And the message was clear: New Orleans' musicians need better support, lest the music that lends this city its identity one day fall silent.

The only other time I'd experienced a noiseless second-line parade was seven months ago. Hundreds gathered at the gate to Louis Armstrong Park. The silence -- unthinkable throughout the hundred-plus-year history of this raucous tradition -- was a carefully thought-through statement. It addressed the violence afflicting the city, the desperately slow process of post-Katrina recovery, and the enabling power of jazz culture for disenfranchised (in many cases, still displaced) communities. Two miles into that procession, not far from where M.L. King Boulevard meets South Liberty Street -- the statement having been made -- the men of the Nine Times Club (in lime-green suits and royal-blue fedoras) and the Prince of Wales Club (in red suits and mustard-colored hats and gloves) started jumping and sliding to the irrepressible sounds of the Hot 8 and Rebirth Brass Bands.

On Sunday a slow, steady rain lent dramatic drips to homemade signs that read: "Living Wages = Living Music," "Imagine a Silent NOLA," "Keep Our Story Alive." But this day, the procession didn't explode into music. When it reached the French Quarter's Jackson Square, Musicians Union president "Deacon" John Moore, a guitarist who played on several seminal R&B hits during his career, addressed the small crowd. "It ain't easy in the Big Easy," he said. "Our musicians are suffering. We hate to come out here like this but we have no alternative."

Benny Jones Sr., the drummer and founder of the Treme Brass Band, has been making music in New Orleans for some 50 years. "It's always been a bit of a struggle," he said, "but now it's become a losing proposition." At issue were the pressures of a hard-hit tourism industry, the increased cost of living in New Orleans, and the need for musicians to demand better pay and some element of nurturing during tough post-Katrina times. Several nonprofit organizations -- the Musicians Clinic, the Renew Our Music Fund, and Sweet Home New Orleans -- have risen to the latter task in the past two years. But while the need they serve remains daunting, the flow of contributions has begun to ebb. Sweet Home director Jordan Hirsch estimates that of the approximately 4,500 working musicians and others in the New Orleans cultural community, "about a third are back and doing OK, a third have yet to return, and a third are here but in unstable situations."

"Historically, musicians have been taken for granted here because it's so common and pervasive," said Scott Aiges, a director at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Foundation and a former city government official, who walked along the parade route. "It's such an intrinsic part of our culture that, when we hear a brass band it's just another day." Aiges thinks there are public-policy solutions to some of the musicians' problems, ranging from promotional strategies to zoning ordinances, and especially tax and other incentives to those who employ musicians. "See, New Orleans culture developed out of a hustle and will always be a hustle," said Ellis Marsalis, the pianist and patriarch to the New Orleans jazz scene, the other night in between sets at the Snug Harbor club. That hustle won't suffice, it seems, during the slow crawl of recovery: Some public policy may be in order.

I went back to Ronald Lewis' house the other day, and he showed me his House of Dance and Feathers, the small museum of artifacts he's collected through his years of involvement with Mardi Gras Indian tribes, Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs, and jazz musicians: There are books and photos, fans and feathers, masks and drums, most of which were assembled anew after Katrina wiped out his original collection.

"They say we're dumb, illiterate, poor people. They chose to put those labels on us. But this is a blue-collar community. We bought houses, raised families, came back," Lewis told me. "I'll draw you in with my culture, but really I want to have a conversation about my community, who we really are."

Tomorrow marks two years since the city was devastated. There's still a great deal of work to do to right wrongs, rebuild homes, and ensure a safer future. President Bush is scheduled to speak at some point, though ever since his infamous Jackson Square address, with its yet-to-be-fulfilled promises, his words are largely unwelcome in this city. A Day of Presence march -- among the many events, some somber, some angry, some celebratory, that dot the day -- will convene at the Ernest Morial Convention Center, the site of last month's Essence Festival. "We're going to demand a regional Marshall Plan," said Edrea Davis of the National Coalition on Black Civic Participation, "to restore New Orleans and the Gulf Coast."

But beyond the rhetoric, immense challenges remain for the city's artists. As Grenada's Ambassador Antoine said at the cultural economy forum: "New Orleans is a perception. When we talk about safety: How safe do you feel? It's not just about crime, it's about how safe do you feel to be you?"

Shares