Jamie Dean had been holed up in his childhood home for six hours when the tear gas canisters came crashing through the windows. It was a little after 4 a.m., the day after Christmas 2006, and Sgt. James Emerick Dean, 29, formerly of the 25th Infantry Division, knew he was surrounded. The white farmhouse was tucked beside a grove of trees in Leonardtown, a rural hamlet in southern Maryland, where Dean's family once raised tobacco. Now, from behind the blinds, Dean could see cops with flashlights creeping around his backyard. He could see police cars on the dirt road outside the house. He could hear the sirens and the shouting and the buzz of the police radios.

It had been a month since Dean had gotten word he'd have to go back to war. He had already served a year in Afghanistan. He'd done and seen things over there he couldn't talk about, and now they were sending him to Iraq. Like tens of thousands of soldiers fighting the post-9/11 wars, Dean was being treated by the Department of Veterans Affairs for post-traumatic stress disorder -- but the Army didn't know that because the Army and the V.A. don't typically share medical records.

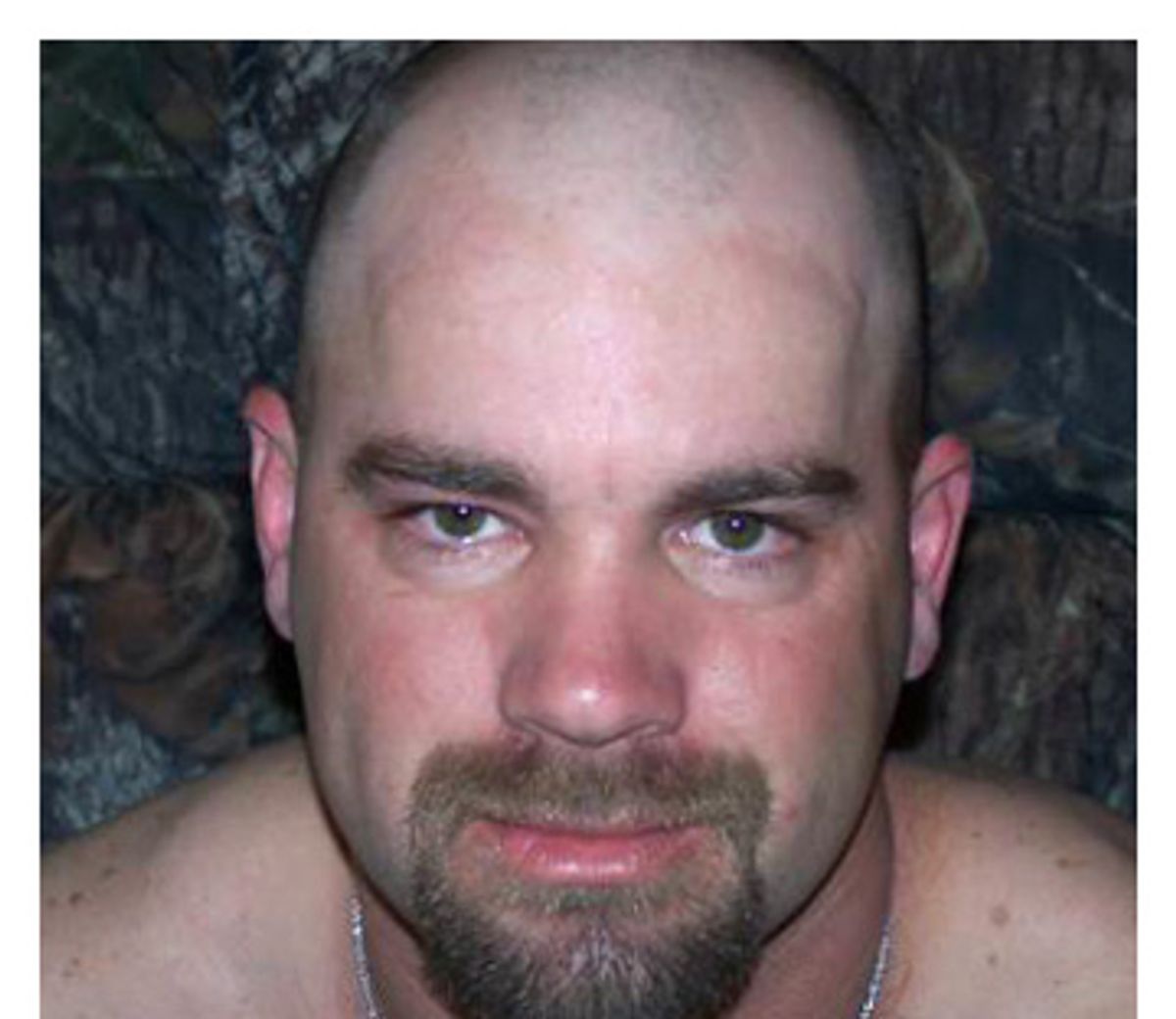

Before joining the Army, Dean was a merry prankster with a contagious smile. But the terror he felt clearing caves in Afghanistan followed him home to Maryland, and despite having a loving family, a new wife and a good job, when Dean got called back up, he began to crack. On Christmas night, he snapped. The outcome would be tragic. The Maryland State Police would be cited for flawed and overly aggressive military tactics. And the whole sorry state of America's need for fighters in Iraq would be exposed.

Christmas Day began with a fight between Dean and his wife, Muriel Dean. It was about his drinking again. Ever since he had received the notice he was being shipped to Iraq, it had gotten heavier and heavier. Late in the afternoon, Jamie fled for Toots, the bar in Hollywood, Md., where he and Muriel had met a year before. The outgoing Muriel, who worked in the personnel department of a computer company, adored her husband. But she was frustrated and angry. She called Jamie at the bar and he came storming home.

"If you wanna be at the bar, be at the bar," she told him. "But if you're gonna get drunk tonight, don't come home." Jamie threw a box of wine onto the kitchen floor and started beating the cupboards with his fists. Glasses shattered and shards fell to the floor. Muriel was scared; she'd never seen him like this before. She went into the bedroom and started putting clothes into a bag to leave for the night. If you leave, Jamie told her, "I'm going to burn the fucking house down." He went out back and got a gas can and lighter. When he came back, Muriel managed to get the gas away from him. "Why would you wanna burn something down we've worked so hard for?" she asked. "You don't know how much I love you," Jamie said, standing in the doorway. "The next time you see me I'll be in a body bag."

Dean fled the house and drove his Chevy Silverado eight miles to his family farm. His father, Joey, lived there alone -- he and Jamie's mother, Elaine, had separated while Dean was in Afghanistan -- but his father wasn't home. Dean started drinking again. He took a shotgun from one of the gun cabinets in the back of the house, and called his mom's house. His sister Kelly, an Air Force medic who has served in Germany and Iraq, answered the phone. To her, Dean didn't sound like himself. He was agitated and then his voice got scarily calm. "I just want to go home," Dean told her over the phone. "Everything will be easier then."

He shot off the gun and then there was silence. Kelly screamed but he didn't answer. Later she would say she thought Dean was dead. "I freaked," she says. "I couldn't get him back on the phone. I couldn't hear any movement on the other end. So I did what any person would do and I called 911."

Police dispatched a car to the house to check on Dean's welfare. When he refused to come out, more police cars rolled up, and officers with guns and flashlights surrounded the property.

At 10 p.m., an officer from the St. Mary's sheriff's department got on the phone with Dean, who was drunk and clearly depressed. He was slurring his words. The officer prattled on, filling the long silences between Dean's mostly monosyllabic answers by trying to assure Dean they didn't want to arrest him, they just needed him to come outside and tell them everything was all right. Dean alternated between despondency and bravado. One minute he whispered that no one understood or respected what he did in the war, and the next, he said that if the police didn't back off it was "gonna get ugly."

Over police radios, information began trickling in: He has guns in the house. (Like most area families, the Deans were hunters.) He has had a fight with his wife. He's a veteran and he's headed back to war.

Around 11 p.m., Dean's family came rushing to the house, but police wouldn't let them up the driveway. "We'll call you if we need you," one officer told Dean's uncle Rob Purdy curtly.

By midnight, two different sheriff's departments had deployed emergency response teams to the scene, surrounding the farmhouse with police vehicles and more armed men. At just after 4 a.m., those SWAT-like teams began firing tear gas into the house. The canisters smashed through the windows and penetrated the walls. Police fired between 40 and 60 rounds into the house, 10 times the amount needed to incapacitate a person. Dean came out the back door, raised his shotgun and fired. For 15 minutes, he paced around, walking in and out of the house, until he finally retreated inside.

Late the next morning, the Maryland State Police rolled up with an armored vehicle. Five minutes later, one of the Charles County snipers accidentally discharged his weapon. Two minutes after he heard the sniper fire, Dean fired his gun from the back of the house, though the shot did not seem to be aimed at anyone. For the next 30 minutes, negotiators attempted to get Dean back on the phone. When they finally did, he told them, once again, to get out of his family's yard or he'd shoot. Officers stepped back toward one of the two "Peace Keeper" armored vehicles that was parked just outside the house. Dean fired again, this time at the ground.

At 12:45 p.m., officers cut power to the house. Dean was surrounded. There was an armored vehicle in the back of the house and one just a few feet from the front door. Both were firing tear gas at him. Finally, Dean stepped out of the front door. As he raised his gun and pointed it at the armored vehicle, a sniper located 70 yards away shot him. The bullet entered his side and pierced his ribcage, heart, liver and stomach. Blood spread over his white T-shirt. One expert shot and Dean was dead.

The Maryland state's attorney's office launched an investigation into Dean's death and ruled it a justifiable homicide. But it harshly criticized the actions leading up to it: "The tactics used by the Maryland State Police were overwhelmingly aggressive, and not warranted under the circumstances," stated its report. "As certainly as [Dean's] death is in part a consequence of his own actions, it is also in large part due to the unfortunate choice of tactics employed by the commanders of the State Police [emergency response team] unit."

One criminal justice expert who reviewed Dean's case, Eastern Kentucky University professor Peter Kraska, said Dean's death epitomized the increasing militarization of law enforcement. He said the aggressive tactics used by the Maryland State Police to "pacify" Dean could only end one way: his being "neutralized" by a sniper's bullet.

The state's attorney's ruling is cold comfort to the Deans. Dean's parents and Muriel have hired a lawyer and plan to sue the agencies involved in the standoff. But the case is moving slowly and has thus far served mostly to erect a wall of silence between the law enforcement officers and the family. St. Mary's County Sheriff Tim Cameron said he thought the Deans deserved some explanations, and that he looked forward to sitting down with them, but now that lawyers are involved, he has to hold his tongue. The Maryland State Police declined requests to comment on the case.

Today, Muriel Dean, 38, hardly sleeps at night. She is distraught by the legal case and the fact that Jamie was recalled by the military. How could the Army have not known that he suffered from severe psychological stress after returning from Afghanistan? Sitting in her neat little house in Hollywood, Md., Muriel rubs her fingers over her forehead constantly, as if she has a terrible headache and is trying to massage it away. The carpet in her living room is well vacuumed and there is a pretty wallpaper border in her dining room, but the house has a ghost. Whole walls are adorned with photographs of Jamie. The unity candle they lighted at their wedding sits between two champagne glasses on a shelf above the couch, and there are two La-Z-Boy chairs upholstered in "real tree" camouflage facing the big-screen TV Jamie loved to watch.

Muriel, who was eight years older than Jamie when he died, has a daughter, 17, and a son, 13, from a previous marriage. Although she had known Jamie only a year before he was killed, she and Jamie had a lot in common, having both grown up in the rural St. Mary's County.

Until the mid-1990s, many residents of St. Mary's made their living working either the land or the water. Dean worked both. Mostly, he helped out on the farm, where every year until 1993, the family harvested 30 acres' worth of tobacco, plus truckloads of corn and other vegetables. The work was hard but Dean enjoyed it. "He loved to get on that tractor and just plow," says his mother, Elaine. "He said he loved the smell of the fresh dirt turning over. He was just in his own little world, nobody bothering him."

Elaine's father, Jamie's grandfather, began crabbing in the late 1970s. He pulled several hundred crab pots a season from the Chesapeake Bay and called his one-man outfit Captain Bob's Seafood. On the weekends, Dean went crawling with him. Dean, his mother says, would rather fish or hunt than just about anything else. And though he was an average student, he was popular, especially with the girls. He had a wide smile and older women giggled to his mother about his "bedroom eyes" and his "cute butt." He played on the high school football team and by senior year was working part time on a construction crew.

In early 2001, Dean's younger sister, Kelly, joined the Air Force. "Jamie said, 'You can have the military,'" says Elaine. "He didn't want anything to do with it." But a broken engagement that spring left Dean unmoored. He started partying every night, coming home near sunrise, hanging out with people who did drugs. His mom worried, but before she even got a chance to sit him down, he sat her down.

"Mom, I joined the Army," she remembers him saying in July 2001. "I leave in two weeks." Elaine was floored. She didn't want him to go, but Jamie had made up his mind. "I've been partying too much," he said. "You worked too hard to raise me right. Now I need to get away from here."

In April 2004, Dean's unit shipped out for a 12-month tour in Afghanistan. Dean, who'd risen to the level of sergeant, led a team of scouts, clearing caves and houses in remote villages. But service overseas wasn't what Dean had expected. He told his Uncle Rob that sometimes the Army wouldn't provide shelter for his team, and they'd have to force villagers to let them sleep in their homes. He also said he routinely got in trouble with his commanders because instead of sending the younger guys into dangerous situations, he'd choose to just go in himself. "It was typical of Jamie to want to take responsibility," says Rob Purdy, a veteran of the Gulf War.

When Dean returned, he moved into the family farmhouse with his dad. He was distant, says Purdy, and he didn't want to do the things they'd always loved, like hunt and fish. Meeting and marrying Muriel seemed to be a godsend. Dean could be compassionate and loving and was learning to be a good stepfather, Muriel says. Her daughter, Tanya, had quickly grown fond of him.

There were problems, however. Most nights, Muriel says, Jamie would come home from his job servicing electrical units for a local air-conditioning repair shop and drink the equivalent of a six-pack of beer. "I'd ask him, 'Why do you need to drink all the time?'" Muriel says. "And he'd say, 'To forget.' I'd ask him, 'Forget what?' But he wouldn't talk about what he did over there. All he said was: 'It takes the pain away.'"

Dean's drinking wasn't the only thing that worried Muriel. He didn't sleep much, and when he did, he had vivid nightmares, and sometimes she'd wake up soaked in his sweat. He had wild mood swings; some days he'd sing "Twinkle, twinkle little star" to her over the telephone at work, and some days he'd tell her that if she ever cheated, he'd kill her. She was never sure what would set him off.

Jamie didn't say much about the war to Muriel or to his mother -- just that they didn't understand, or that they didn't want to know. Jamie did admit he had seen his friends die violently. He also told vague stories about kids with bombs strapped to them who would approach the soldiers. Muriel and Elaine don't know for sure if Jamie ever shot children, but they suspect he may have. "When Jamie did something wrong as a kid," Elaine says, "his conscience would eat him up." And whatever he'd done or seen in Afghanistan seemed to be eating him alive.

For weeks in late 2005, Muriel encouraged Jamie to seek help at the V.A. clinic in nearby Charlotte Hall, Md. Finally he relented. At his first appointment, he screened positive for depression, alcohol abuse and PTSD. According to his V.A. medical records, Dean was having "recurrent intrusive thoughts," as well as pervasive feelings of numbness, anger, anxiety and detachment from others. He told a doctor, "I'm tired of feeling bad."

About six weeks after his first visit, doctors at the V.A. clinic started Dean on medication: fluoxetine (generic Prozac) and trazodone for the depression. But Dean's local V.A. clinic didn't offer counseling; if he wanted talk therapy (an essential part of treatment for PTSD), he'd have to visit the V.A. hospital in Washington, D.C., a 90-minute drive from St. Mary's. Muriel says he tried once, but got lost and so frustrated he turned around and never went back.

Vincent Tomasino, a V.A. psychiatrist who saw Dean a few times in Charlotte Hall, remembers him as charismatic. Tomasino says that traveling into an urban area like Washington can be a frightening experience for a combat vet, especially one suffering from PTSD. "You look around and you feel like you wanna carry a 9 millimeter," he says.

In February 2006, Tomasino upped Dean's antidepressant dose, and added Abilify, an antipsychotic medication sometimes used to treat schizophrenia. To that, he added amantadine, which counters some of the potential side effects of Abilify. In May, the doses went up again, and though the V.A. called and sent letters informing him of counseling options, Jamie never made it to a session. What's more, he was not disciplined about taking the medication, which made him feel foggy and strange.

In August, Muriel began to worry that Jamie might have to go back to war. He'd been honorably discharged after completing nearly four years of service, but she'd been watching the news, seeing stories about how the Army needed bodies, and was extending tours and calling up Individual Ready Reserve soldiers like Jamie. Jamie worried, too. That month, he and Muriel mailed forms to the V.A. to have Jamie ruled disabled because of his ongoing mental health problems. An official disability label, they hoped, would keep Jamie from getting redeployed. But the process was slow and in the middle of September, the V.A. sent the couple a letter saying they had a backlog of claims and a ruling on Jamie might be delayed.

Nonetheless, making the effort seemed to calm Jamie a bit, and Muriel says that by the fall of 2006, he was getting better. The couple had moved into a new house, which Jamie called his "happy little home." He cooked -- spicy foods like chili were his favorite -- and helped out with the grocery shopping. Muriel wasn't able to have any more children, but the couple started talking about a surrogate. They made an appointment to see a specialist in Baltimore in January.

Then, on Nov. 28, 2006, five days after Thanksgiving, Jamie got the letter they'd both feared. "Pursuant to Presidential Executive Order of 14 September 2001, you are relieved from your present reserve component status and are ordered to report to active duty."

This time, he was going to Iraq; and he had to report in less than two months. Muriel and the rest of Jamie's family were devastated, but they tried to stay positive; Muriel called to find out about Jamie's disability application and was told it was still being processed.

Dean seemed to shut down. He started drinking more. He'd come home at night and tell Muriel they needed to talk, but then he'd sit silently for half an hour, unable to get whatever he had inside him out.

Dean's boss, Tommy Bowes, who says Dean was a model employee, saw that the couple were struggling to prepare themselves for his deployment. He offered to give Dean the month off with full pay, but Dean declined the offer. "I don't want time off," Bowes remembers him saying. "I wouldn't know what to do with myself."

Dec. 23 was Dean's 29th birthday, and the family took him out to Olive Garden for dinner. The next night, Christmas Eve, Jamie and Muriel went to his grandpa's house, as was tradition. Jamie had promised Muriel he wouldn't drink too much, but on the way he asked her to stop for a six-pack, and once he'd finished that, he started throwing back glasses of wine. Near the end of the night, Purdy, his uncle, found Jamie outside on the deck, crying. He'd been having nightmares about dying in Iraq. "I can't concentrate on my medicine," Purdy remembers him saying. "I can't be like this over there. I gotta be ready to go. I gotta get ready to go." Purdy tried to calm him down, saying maybe he wouldn't have to go once the Army found out he was undergoing treatment for PTSD. But Jamie was despondent. "No, I'm going," said Jamie. "You know once they get me, that's it." Jamie hugged his uncle tight -- a real hug, Purdy says, not a guy hug -- and said, "I love you, man." It was the last time Purdy saw his nephew.

Muriel doesn't remember much about the days after Jamie's death. She says she knew that once he'd holed up in the farmhouse and been surrounded, he probably wouldn't come out. "He was stubborn," she says, "and he would have rather stayed in there than come out and have people think he was crazy."

Eight months later, the Deans continue to grieve, each aiming their anger at a slightly different target. Jamie's sister Kelly can't help blaming herself. Calling the police that night, she says, was the biggest mistake of her life. In Purdy's mind, if the Army had known about Dean's diagnosis, they might not have sent the letter. Both Purdy and Kelly have tried to get answers from the Army about why it recalled a veteran undergoing treatment for PTSD. Wasn't there a system in place that flagged veterans with disabling illnesses from being deployed? The Army's human resources office says that no such system exists; it's up to the soldier to prove his or her condition after receiving deployment orders.

It's impossible to know whether Dean would have been spared redeployment had he gotten all his paperwork in order after he received his orders. (There was no guarantee he would be exempted. Reports have shown that soldiers with severe mental illness have been ordered to duty in the post-9/11 wars.) But then, Kelly says, after her brother received the letter, his pride took over and he didn't want to protest. "He was afraid of looking weak."

Today, despite the state's attorney's ruling that shooting Jamie Dean was "justified," Muriel Dean and Jamie's parents still want answers. They want to know why two police vehicles designed for heavy combat were deployed to the isolated farmhouse. They want to know why police found it necessary to launch more than 50 tear gas canisters through the windows and walls of the family's house. Why the escalation? Why force a man they knew to be a veteran into a combatlike situation? Pacifying the inebriated Jamie could have been so easy. "If they'd just left him alone and let him pass out," Muriel says, "he'd be alive today."

Shares