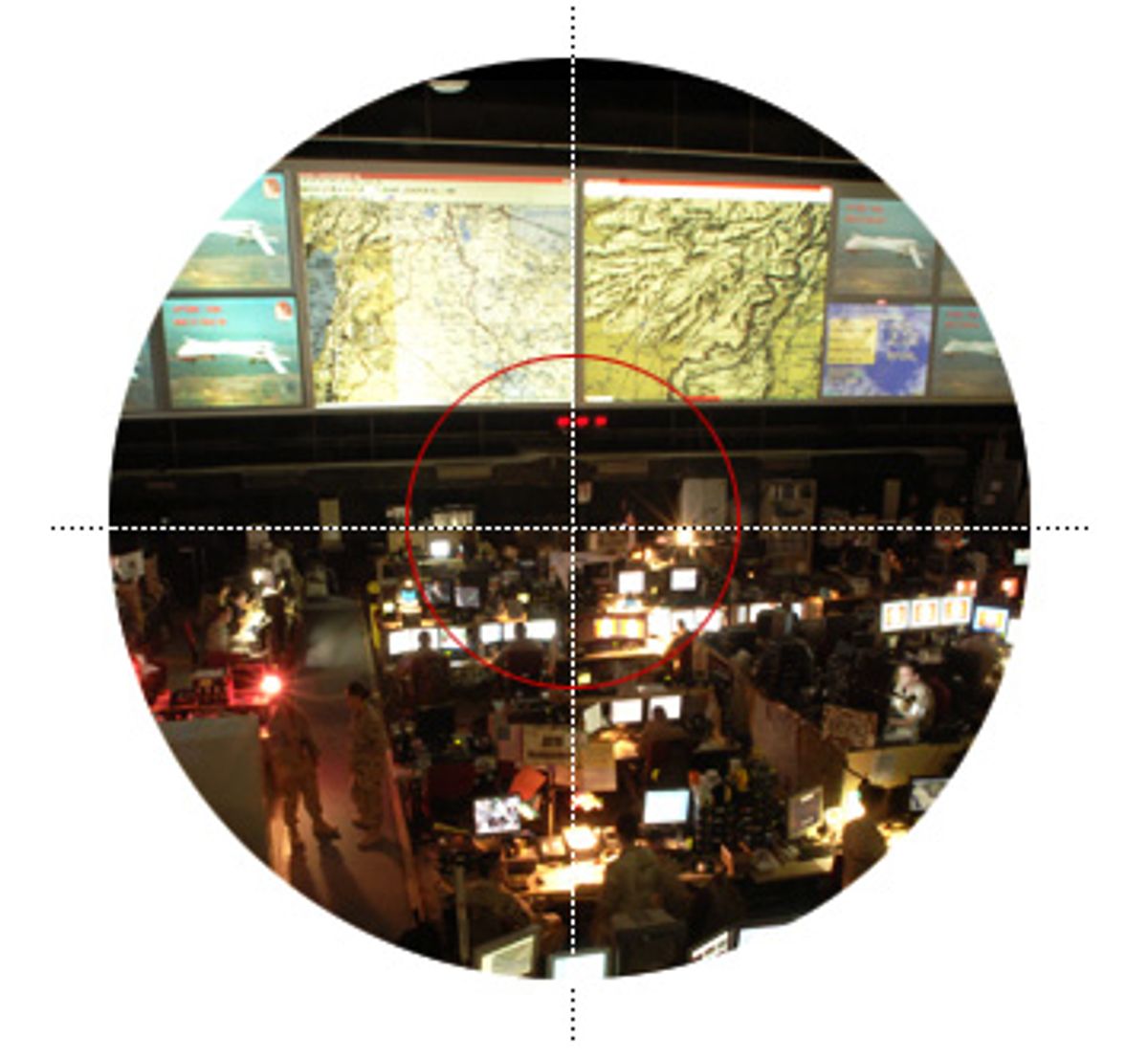

The cavernous control room used by the U.S. Air Force to manage the air wars in Iraq and Afghanistan looks exactly how you'd expect it to look in a Hollywood movie. The lights are low. Around 50 camouflage-clad men and women lean forward in their chairs, staring intently at rows of computer screens glowing with multicolored graphs and fluctuating displays. They sometimes glance up from the banks of computer monitors to gaze at a sweeping panel of large television screens mounted on the front wall. Two massive, side-by-side screens in the center display digital maps of Iraq and Afghanistan. Swarms of U.S. aircraft above the war zones are represented by green labels that move about each map, gravitating toward wherever U.S. troops are fighting on the ground, in case they need backup.

To the left and right of those large maps are four smaller screens. Each is about 5 feet wide, displaying remarkably clear live footage from cameras mounted on the Air Force's un-manned Predator drones that buzz incessantly above Iraq and Afghanistan. The Predator drones, however, are not filming a raging firefight, or a bridge about to be strafed from the air.

They are stalking prey.

You see a man, walking through a shrub-dotted, dusty field. A small dog wanders behind him. Another screen shows a group of individuals, standing huddled together on a city street, looking like they could be chatting about a ballgame. A third Predator tracks a figure getting into a car, following as the car snakes through traffic. Yet another screen stays fixated on a single squat house surrounded by what looks like a low cement wall, as if someone is about to emerge from the front door.

The scenes look misleadingly pedestrian. The miniature people on the screens do not know they are being watched. "We are looking for individual people," Lt. Col. Walt Manwill says, as he stares up at the massive screens. "Especially when you are killing people, you want to make sure you do it right." Manwill, a blockish former pilot whose call sign is Fridge, is a chief of combat operations here, on what the Air Force simply calls "the floor." He handles one of three eight-hour shifts in a job that runs 24 hours a day.

Targeters here show me recent footage of two men on the ground in Iraq. The two men, far below the Predator drone's gaze, appear to be setting up a mortar on a city street. They are in the shadow of a building just feet away. Suddenly, the two men explode. Everything around the men, including the buildings, looks unharmed. But when the dust clears, the two men are wiped away. A small bomb, tailor-made for hunting single individuals, has done the job.

An Air Force colonel describes these operations to me as "getting Bubba." This has become a key component of the air wars in Iraq and Afghanistan -- and the Air Force has developed it into a science. Air Force officials say the operations are highly effective in targeting enemies of the United States, while minimizing civilian casualties in the war zones. But some experts on international law note that the U.S. has flown into legally murky territory, akin to the Israelis' controversial practice of "targeted killings" in battling Islamic militants.

The air wars the U.S. is fighting have escalated dramatically over the past few years. In 2004, the Air Force dropped 371 bombs in Iraq and Afghanistan. Every year since then that number has increased. Last year, 5,019 bombs were dropped. (Air Force officials caution that those statistics may be misleading now in terms of a trend, since in recent weeks, they say, things have been much quieter with bombing operations in Iraq.)

The Air Force agreed to give Salon two days of unrestricted access in early February to what is officially called the Combined Air & Space Operations Center, the technology and personnel brain center controlling the air wars over Iraq and Afghanistan. The visit, allowed under the condition that some secret information be withheld from this article, included several hours on the floor over the two days, watching operations unfold.

From this dusty air base in the Persian Gulf region, rarely visited by nonmilitary personnel, the Air Force quietly manages nearly 2,000 sorties a day above perhaps the most complicated battle spaces in the history of warfare. The logistics alone are dizzying: The Air Force hauls 3.7 million pounds of fuel above Iraq and Afghanistan daily to refuel aircraft in flight.

When it comes to dropping bombs, most of the airstrikes carried out by the Air Force are executed to support troops on the ground pinned down in a firefight, called "troops in contact." Other branches of the U.S. military regularly conduct airstrikes; the Army and Marines have hundreds of attack helicopters working in the war zones, supporting U.S. ground troops much more often than does the Air Force. But the Air Force has also enthusiastically embraced what is called the Intelligence Surveillance, Reconnaissance part of its mission. In Iraq and Afghanistan, this means using advanced technology to locate individual people, and then tracking them using the cameras on the Predator drones and other aircraft. These operations can go on for long periods of time. The Air Force recently watched one man in Iraq for more than five weeks, carefully recording his habits -- where he lives, works and worships, and whom he meets.

The military may decide to have such a man arrested, or to do nothing at all. Or, at any moment they could decide to blow him to smithereens.

The remarkably precise airstrikes rely on a battery of technology: the drone aircraft, 3-D satellite images, and increasingly small precision weapons guided by lasers or Global Positioning Systems.

"If it is a bad guy, a known terrorist, we can find him," says Lt. Col. Kenneth Edwards, another officer running the floor during my visit. "We watch them for a while. We determine a pattern of life and a positive identification," he says, peering through his glasses at a small image of a man on one of the screens. "Would you rather look in his window and possibly get killed, or would you rather look at him from afar?" he asks, referring to the danger of ground operations.

"On occasion, when there is just one guy in the middle of nowhere and we've got him, we will target that individual from the air," affirms Col. Gary Crowder, the commander of the operations center here.

What you hear from Air Force officers here is that Army Gen. David Petraeus' counterinsurgency strategy has been fully incorporated into the air war. That is, the U.S. is killing the bad guys -- but not civilians. All the technological prowess is key to that mission.

But are the efforts to limit collateral damage really working? When the Air Force has enough time to thoroughly plan a strike, the answer is yes, according to Marc Garlasco, who was the Pentagon's chief of high-value targeting at the start of the war in Iraq and is now a senior military analyst at Human Rights Watch. "When they have the time to plan things out and use all the collateral damage mitigation techniques and all the tools in their toolbox, they've gotten to the point where it is very rare for civilians to be harmed or killed in these attacks," Garlasco explains. But he emphasizes that it's still dicey when the Air Force has to drop bombs, in short order, to back up troops in a firefight. "When they have to do it on the fly and they are not able to use all these techniques, then civilians die."

Air Force officials admit they were stung by a series of headlines last summer about civilian deaths from airstrikes, particularly in Afghanistan. News reports from last June contained allegations of 90 civilian deaths from U.S. airstrikes over a 10-day period. Afghan President Hamid Karzai held a news conference that month, saying air operations had been "careless." On June 19, the Agency Coordinating Body for Afghan Relief, representing nearly 100 humanitarian groups, released a statement of "strong concern" about the death toll.

Since that time, Garlasco says, "I have not seen a single incident of civilian casualties in Afghanistan."

The Air Force learned the hard way that inadvertently killing and injuring civilians or damaging property is counterproductive to the overall cause. "We went back and looked at our procedures -- how we use air, why we use air and under what circumstances," explains Crowder. "We changed the way we do business."

"It's just like a business," agrees Maj. Gen. Maury Forsyth, the deputy commander of Air Force operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. "Every time you have one unsatisfied customer, you have to have nine satisfied customers to counteract that," he says during an interview in his office. "I'll put it this way: All of the military and political benefits of 10 perfect airstrikes targeting insurgent leaders can be lost in a few seconds by one strike that goes awry and causes civilian casualties."

The technology the Air Force relies on to kill Bubba, but not his neighbors, is mesmerizing. It also makes the process of killing another human being eerily impersonal.

On the floor, once Bubba is up on the screen, targeting officials can quickly call up satellite images of his location. They have at their fingertips high-fidelity images less than 90 days old of nearly every square foot of Iraq and Afghanistan -- a vast amount of data. By overlaying two images of the same location taken from separate angles, and donning a pair of gray 3-D glasses (I wore a pair), a stunning real-life-looking, 3-D image of Bubba's house appears on a computer screen: There is Bubba's yard, the tree in Bubba's yard and so on. Using a mouse to point and click, a computer quickly determines the size, height and precise location of nearby structures.

The Air Force uses the live images from the Predator drones to try to see if any innocent civilians are near a target. The 3-D satellite images are used to help identify and measure the precise distance to other nearby "collateral concerns" -- close-by buildings or any other thing they don't want to damage in an airstrike. "In Iraq, if it looks like we are going to kill a civilian by dropping a bomb, we don't drop a bomb," says Crowder.

Afghanistan is bigger than Iraq, and bigger bombs -- up to 2,000-pounders -- are often used there. The targeters planning strikes there sometimes have the luxury of wide-open spaces and enemy forces that tend to gather in relatively large groups, sometimes 20 to 25 fighters. Many more bombs were dropped in Afghanistan last year (3,572) than in Iraq (1,447).

The combat zones in Iraq tend to be more urban, and more complicated. But it doesn't take much of a bomb to kill one man. So the Air Force has altered one of its relatively smaller munitions into a kind of sniper's weapon. The bomb usually carries 200 pounds of explosives -- but the Air Force pulls out most of the explosives, leaving in less than 30 pounds, and fills the rest of the bomb with cement. The bombs have become so useful for narrowly targeted missions that two-thirds of the Air Force fighters now go up every day with this weapon nestled under the wings.

The Air Force has developed other methods to control bombing damage. Pilots can now quickly alter the settings on a bomb to delay the detonation anywhere from 5 to 25 milliseconds. That change can cause the plummeting bomb to burrow deep into the earth before exploding. "It is incredible," says Col. Bill Carranza, an Air Force attorney who watches Predator images in real time to help commanders determine when airstrikes are legal. "A 500-pound bomb with a five-millisecond delay -- five people in a room, somebody will get up and walk away."

The entire chain of events, from stalking to airstrike, can happen very quickly. This occurs when the location of a valuable target is only known for a brief period of time -- they know where Bubba is, but they don't know long he'll be there. The Air Force calls these "time-sensitive targets." In such situations, the entire process -- pulling up the 3-D satellite images, estimating possible civilian casualties, choosing weapons -- can necessitate completion in less than 30 minutes.

While the Air Force handles that whole process, Army or Marine commanders on the ground always make the final decision on whether to drop a bomb. But the Air Force knows whom to look for. The Bush administration -- the president himself and the secretary of defense -- have established broad categories of people who can be targeted, according to Air Force officials. Using those parameters, the commanders in Iraq and Afghanistan literally draw up a list of names. Lawyers, like Carranza, and intelligence specialists review the intelligence behind each name on that list.

That review is important under international law. The Law of Armed Conflict, a web of international treaties including the Geneva Conventions, prohibits the intentional killing of civilians unless they are taking a "direct part in hostilities." This gets very complicated when fighting an insurgency.

"A problem is that Bubba is not a member of an army that is a party in a conflict," explains Gary Solis, a former Marine prosecutor at Georgetown University Law School. Solis says there is disagreement among experts about whether, for example, a terrorist is taking a "direct part in hostilities" when he is out walking his dog. "There is definitely an interpretational issue here," Solis says. "We are pressing the envelope in the law of armed conflict when we do this. I think some of the international community would say this is unlawful."

Last August, two Army helicopter pilots were downed in Afghanistan, awaiting rescue. There was an individual located 400 yards away who -- for reasons that can not be printed in this article -- it was determined was posing a clear threat to the stranded pilots. But then this individual didn't make any physical move toward the pilots, appearing to take no overt hostile action. So was he taking a direct part in hostilities?

In this case, the commander on the ground put the question to the Air Force attorneys watching from the floor. "The question was, 'If I have to kill this guy, is there a legal concern?'" Carranza, recalls. Carranza sent forward a decision and a recommendation. "I told them, yes, you could [bomb him]." But his advice was to wait for more cause to do so. "My recommendation was, 'You probably have enough now. [But] if you get a few more things, you've got a real solid case,'" he says.

This was happening quickly, in real time, under obviously tense circumstances. Carranza says that in the end, the commander chose not to drop a bomb and the pilots were safely rescued while the Air Force kept an eye on the threat 400 yards away. "I have to tell you," Carranza says, "I don't envy the people who have to make those choices."

All of the technological and tactical advances during the Iraq war have meant that commanders have had to make those choices more often. "Prior to this, we never did targeting of individuals," says Crowder. "Full-motion video is in such high demand now," he says. "I can follow a guy back to his house and then take out the entire house of IED makers," he says, referring to insurgents using roadside bombs.

The Air Force may be in this business for a long time. For all the talk in the United States about getting troops out of Iraq, there is a sense among Air Force officials that they are going to be fighting from this command center long after there are fewer boots on the ground. During my visit, Air Force Secretary Michael Wynne arrived to attend a ribbon-cutting ceremony for a new, very large and very permanent-looking living quarters for Air Force personnel stationed here.

Lt. Col. Bill Pinter, who does strategic planning here, says nobody expects the mission to end anytime soon. "They don't have an Iraqi Air Force," he tells me, referring to the Iraqi government's nascent efforts to establish some sort of air power. "The Air Force will be the last ones to go out the door."

Shares