In 2003, Samantha Power won a Pulitzer Prize for her book "A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide," in which she chronicled the United States' responses to the major genocides of the 20th century. But that's just one of her accomplishments. Power, 37, is a Harvard professor and founder of that university's Carr Center for Human Rights Policy. She is a prominent voice on stopping the genocide in Darfur, Sudan, and addressing numerous trouble spots around the world. She has shot hoops with fellow Darfur activist George Clooney, and once proclaimed herself the "genocide chick."

Beneath her sense of humor is a fierce idealism and dedication to improving world affairs. Now, Power is immersed in what she considers the toughest challenge yet in her action-packed career: serving as a senior foreign policy advisor to Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama.

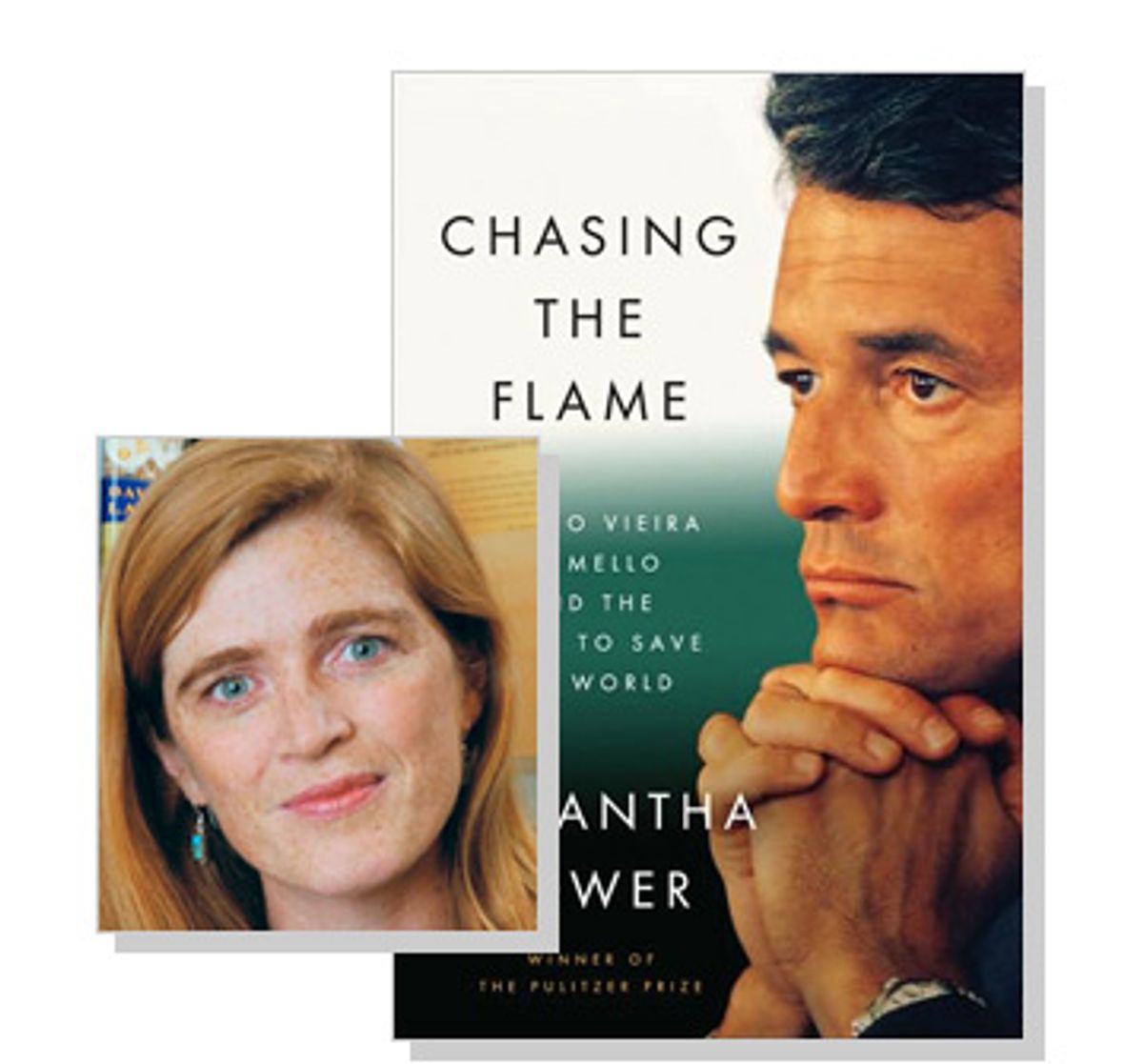

The demands of that job have only risen since she first began working for Obama when he joined the U.S. Senate in 2005. But Power also found time to produce another book, published last week: "Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World." The new volume is a biography of the revered United Nations envoy -- once described as a cross between Bobby Kennedy and James Bond -- who was killed in the catastrophic bombing of U.N. headquarters in Baghdad by insurgents during the early stages of the U.S. occupation of Iraq. The book is also a treatise on why the world needs the U.N., and the lessons Vieira de Mello learned throughout his career, now more than ever.

"He is the man for dark times," Power says of Vieira de Mello, whom former U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan once called the U.N.'s "go-to guy." "He had a 35-year head start thinking about how to mend broken people and broken places, these questions that are consuming us now."

During Vieira de Mello's career with the U.N., as Power details, he met with members of the Khmer Rouge and Serbian genocidaires, his attempts to broker peace with the latter earning him the nickname "Serbio." Power says she sees a strong synergy between Vieira de Mello's principles and Obama's concept of foreign policy -- with their emphasis on justice, human rights, security and, perhaps most controversially, direct diplomatic engagement with foreign adversaries.

Power sat down with Salon recently in New York for a wide-ranging conversation about Vieira de Mello's legacy, going to work for Obama and the colossal challenges facing whichever candidate becomes the next U.S. president.

Your new book is out and you've been on the road with Sen. Obama. Are you having fun?

I'm not having as much fun as you would expect because I don't know that I've ever taken anything so seriously. I think the campaign is the most important thing I've ever been associated with. So I'm really tense and actually quite miserable.

How did you end up working for Sen. Obama?

His office called me when he began serving in the U.S. Senate in early 2005. He had just read "A Problem From Hell" and wanted to meet to discuss fixing American foreign policy. I thought, "Well that's interesting -- clearly he's in some other league." I mean, who spends Christmas reading a dark book on genocide? No other politician had ever contacted me to discuss it.

We were supposed to meet for only an hour but ended up meeting for three or four hours at a steakhouse. Suddenly it was almost midnight and I heard myself saying to him, "Why don't I just quit my job at Harvard and work in your office for a year or whatever?" I didn't even know what I was proposing, but he said, "Great."

How did you make the leap from journalist to going to work for a political candidate?

I got into journalism not to be a journalist but to try to change American foreign policy. I'm a corny person. I was a dreamer predating my journalistic life, so I got into journalism as a means to try to change the world. I didn't get into journalism by any means to win a Pulitzer Prize or do anything like that. Back then, I was obsessed with what was going on in Bosnia. I went over there because of that; I tried to get a job at NGOs ... But I didn't wait this long [to work for a candidate] because I was such a hardcore reporter. It was because I never met anybody worth doing it for before.

You were born in Dublin, Ireland, and grew up mainly in the United States. How did you come to write about genocide?

I read about the Holocaust in college [at Yale University]. Right around the time I graduated there were the concentration camps out of Bosnia with these emaciated men behind barbed wire. And I could tell a long story about why that moved me ... but it was so moving.

Genocide was the lens for me. And you can see genocide whether you go to Rwanda or you don't go to Rwanda, but you still have to figure out a way to inject concern for human beings into our foreign policy. This is what was so gratifying to me about the way Obama read "A Problem From Hell" -- for him it was about fixing American foreign policy.

What is the biggest foreign policy challenge for the next president?

The next president is really going to have to walk and chew gum at the same time, because no long-term peace in the Middle East is possible until we get some kind of modus vivendi in the Arab-Israeli situation. And then the singular challenge is being handed two wars, two live battlefields -- and one of them in the heart of the Middle East. It can't be an afterthought as it was in the Bush administration.

Afghanistan is a hugely important theater -- and of course we neglected it by going to war in Iraq. We probably should not fall prey to this romantic idea that simply by getting out of Iraq and retraining our resources on Afghanistan that solves the problem. We have major deficiencies with what the international system is capable of in terms of reconstruction and development, and that's ultimately what will stabilize Afghanistan -- stop the resurgence of the Taliban, temper the violence, stave off the outbreak of widespread civil war. But while you do that you have to get the other train running: building up infrastructure, roads and schools, the things that are going to actually stabilize the country long term.

And along with all that the next president will have to keep an eye on Lebanon, North Korea, Darfur, China as an economic and geopolitical dynamo, and Russia and its regional adventurism.

In light of all the questioning of Obama's "experience," you've said he has dirt under his fingernails, and that he would bring a new America to the world. How would he do that?

The idea that he doesn't have experience is nuts to me. He's a constitutional law professor. I happen to miss the Constitution; I thought it was a good document. That's a huge component of being a president when you're combating terrorism and you're trying to restore American values.

The fact that he used to work in the inner city, that's the dirt under his fingernails. If people are an abstraction to you, it's going to show. If you're living with people, if you're working in the inner city, you see the human stakes of it all. He's also lived abroad, so he's comfortable crossing boundaries.

You've said that the Bush administration has diminished the U.S. government's credibility among its own citizens. Can the next president fix that?

I don't think the next president can just show up and have it restored. Whoever wins is probably going to win by a narrow margin. One of the reasons Obama is so appealing to me is that he doesn't take the American people for granted; you don't stop having this conversation when you enter the White House. None of the major foreign policy challenges on the horizon can be tackled if we don't have a thick domestic base. We can't do foreign aid, we can't get out of Iraq, succeed in Afghanistan, close Guantánamo and end torture policy without actually talking to people about the costs of that.

Why did you choose Sergio Vieira de Mello as the subject of your new book?

I think to some degree our models are off. We still talk a lot about transnational stress, global demons and things crossing borders, and yet our instincts are to focus on statesmen or people who operate within boundaries. We don't have models or instruction from people whose lives are themselves commensurate to the challenges that we recognize as the major ones on the horizon.

You've talked about what a great teacher Vieira de Mello is. What has he taught you?

I think Sergio makes me see dignity. His great line, and actually my favorite line in the whole book, is, "Fear is a bad adviser." I love that. It's so simple. And then that humility and curiosity are very important -- but also a sense of fallibility without paralysis.

I think Obama has all those things in spades. I like to think that as I get older I'm getting better at spending time with people who have qualities that make them worth spending time with. My decision to leave Harvard and go work on foreign policy, in the minority party in the U.S. Senate at that time, it was a terrible year. Obama was great, but on national security the Republican committee chairmen were so deferential to the president that it was hard to get anything done. It was the worst year of my professional life, but it was the education of Samantha Power. You spend time with Obama and you learn things. And hopefully I could bring a little bit of what I learned from Sergio to him as well.

In the book you cite Vieira de Mello as saying that countries will kick and scream at the United Nations, but that at the end of the day they get the U.N. they want and deserve. As a career U.N. diplomat, what kind of reforms was he advocating?

Nothing will happen at the U.N. as such, in that building, until and unless states change. The major reform, the first reform would have to come from this country deciding that it's in our interest to have a stronger body to deal with international threats. We haven't come to that conclusion. We have to believe in international law and binding ourselves to international standards in the interest of getting others bound to those same standards. We haven't made that decision yet.

We have to pay our dues on time. We really have to want the U.N. to be well-endowed, and then we can use our diplomacy to make others invest in it, too. The real [potential for change] that Ban Ki-moon, the secretary-general, has is minuscule compared to what specific countries within the U.N. have. But for the last 60 years the debate about U.N. reform has occurred at the U.N. instead of in world capitals.

The Bush administration has a long-standing policy that it doesn't engage with terrorists or dictators. Is there a time when the United States should?

Absolutely. I'm with Barack on this. But it's not indefinite. Barack's point is you don't treat meeting with America as if it's in and of itself some great reward. It doesn't buy the other side anything. In fact, today it hurts a lot of people to be in business with the United States. So what you do is you meet in order to achieve things. You meet in order to know your foe, if it's a foe. You meet in order to get international wind at your back so that America is not seen as the problem -- [Iranian President Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad is the problem. You meet because you want to stop lumping together the unlike -- al-Qaida, Hamas, Iran, Iraq.

You recently wrote in Time magazine that the U.S. needs to "rethink Iran." What did you mean?

We lunge between two extremes, neither of which is helpful. One is the Bush-Cheney saber rattling -- hyping of the threat, alienation of international stakeholders because of the sense that this is about ideology rather than about problem solving. In saber rattling we're ultimately strengthening Ahmadinejad's base, because the one thing that will unite Iranians -- whether secular, moderate, Islamic or nationalist -- is the idea that we're going to come and attack their country.

On the other hand, there are people who are so disgusted and disillusioned with the Bush years that they romanticize in some way this wily Iranian head of state instead of acknowledging that the Iranian government is by all accounts a supporter of terrorist acts, or that Ahmadinejad is a head of state who denies the occurrence of the Holocaust and has made no secret of his militant animosity toward Israel. My feeling is that we need something in between the extremes that acknowledges that this individual, this regime, is dangerous and unconstructive -- but that also acknowledges we have strengthened its hand by saber rattling, invading Iraq, dislodging the Taliban and rendering Iran the regional heavyweight.

To neutralize the support Ahmadinejad has domestically, we need to stop threatening and to get in a room with him -- if only to convey grave displeasure about his tactics regionally and internationally -- and then try to build international support for measures to prevent him from supporting terrorism and pursuing a nuclear program. If we're ever going to actually put in place multilateral measures to contain Iran, the only way we're going to do that is if we do it in a more united way with our allies.

How do we get out of Iraq?

We have to put Iraqis at the center of our planning and our thinking, which is not something we've done naturally at all -- from the '80s when we supported Saddam Hussein, when he was using chemical weapons against his own people, to the '90s, when we had sanctions against the regime and paid very little attention to the toll of those sanctions on Iraqi civilians. And then, in the decision to go to war and the way we went to war -- which was so not about Iraqis, as shown by our refusal to protect civilians and our failure to do adequate postwar planning.

We need to be incredibly sensitive as we leave Iraq to the welfare of Iraqis who are going to be left in our wake. That potentially entails the idea of sectarian or ethnic relocation if people are in a mixed neighborhood and feel that they'd be safer in a more homogenous neighborhood. Also, [it entails] massive support for neighboring countries that have taken in 2 million refugees, and some very systematic effort between now and the time we begin leaving to build funding and resource streams to internally displaced people.

We have shown again and again that we care about Iraq only insofar as it serves our interests. But I think it's time to show not only Iraqis but the rest of the world that at least as we leave, we're leaving with a very vigilant eye on how to mitigate the consequences of our actions.

Shares