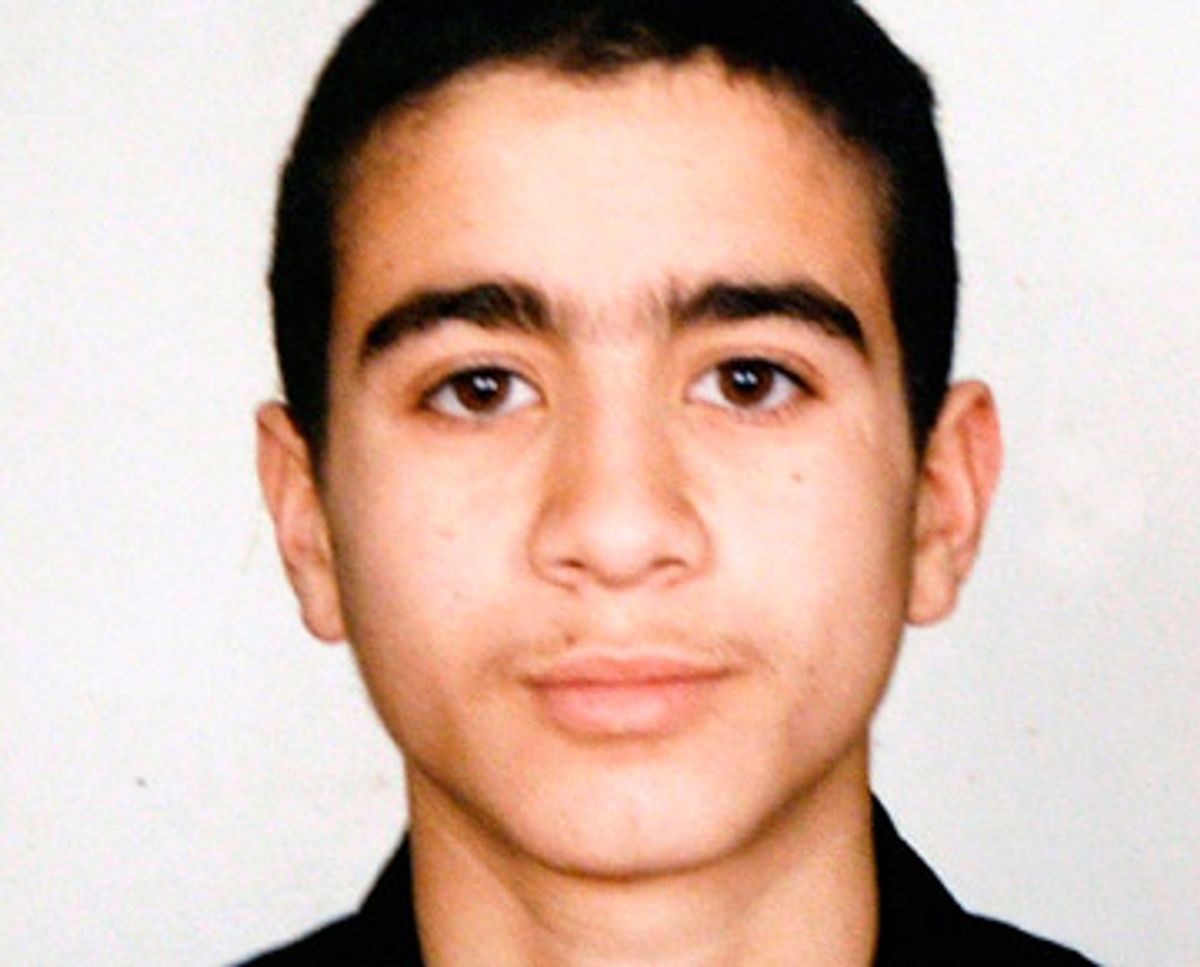

When Mohammed Jawad took the stand in a courtroom at the U.S. Naval base here late last week, he described a litany of abuse he has endured while detained at Guantánamo, including a sleep deprivation regime known colloquially as the "frequent flyer" program.

"Day and night, they were shifting me from one room to another room," Jawad said. "I don't remember how much time I slept, but it was only a short time before they were knocking on my door and shifting me from place to place. No one answered me why they were giving me this punishment."

Military records showed that during a 14-day period in May 2004, Jawad was moved from cell to cell 112 times, usually left in one cell for less than three hours before being shackled and moved to another. Between midnight and 2 a.m. he was moved more frequently to ensure maximum disruption of sleep.

Such tactics used against a detainee would have been severe under any circumstances -- Department of Defense guidance limits sleep deprivation to a maximum of four days -- but in the case of Jawad, they are particularly disturbing because he was a scared and suicidal teenager at the time. Jawad's military-appointed lawyer, Maj. David Frakt, described the tactics as "sadistic and pointless," and moved to dismiss the charges against his client on grounds of torture.

Jawad was arrested by Afghan police in December 2002 after allegedly throwing a grenade into a U.S. army vehicle in Afghanistan that severely injured two U.S. soldiers and their Afghan translator. Frakt argues that Jawad was drugged and forced to fight with Afghan militia. Jawad doesn't know his exact birth date, but was 16 or 17 years old at the time. In early 2003, he was brought to Guantánamo.

According to government records obtained by the Associated Press under the Freedom of Information Act, more than 20 detainees under the age of 18 have been brought to the prison camp since 2002. The treatment of underage prisoners at Guantánamo, largely in defiance of international law, is one of various ways in which the Bush administration's policies have tainted prospects for Guantánamo detainees ever to be brought to justice under U.S. law.

Although most of the 20 juvenile detainees have now been released, three remain, having spent more than a quarter of their lives at Guantánamo. The other two juvenile detainees were each only 15 years old when they were apprehended. Mohammad El Gharani was arrested at a mosque in Pakistan and brought to Guantánamo in early 2002. Omar Khadr, a Canadian, was apprehended in July 2002 after a firefight in Afghanistan that resulted in the death of a U.S. soldier. Held for several months in Afghanistan, he was barely 16 when he arrived here later that same year.

The presence of juveniles at Guantánamo first came to light in 2003, when media reports revealed the age of the youngest detainee at Guantánamo -- who was only 13 years old. Unable to explain how a 13-year-old could be classified as being among "the worst of the worst," as top Bush officials had described Guantánamo's prisoner population, the Pentagon realized it had a PR problem on its hands. It quickly created a special camp for the three detainees between ages 13 and 15. At Camp Iguana, these children received math and English classes and access to a social worker and recreational facilities. Bizarrely and perhaps without any sense of irony, they were permitted to watch movies including "Cast Away." Defense Department officials proudly gave tours of the special facility.

That year, on behalf of Human Rights Watch, I had several meetings with Pentagon representatives to discuss the fate of these children. In early 2004, they were released to UNICEF in Afghanistan for rehabilitation. But whenever I tried to raise the case of Omar Khadr (we were unaware of El Gharani and Jawad's cases at the time) I received the same response: "Khadr is off the table; we will not discuss Khadr."

Unlike with the three boys held at Camp Iguana and released for rehabilitation, the Pentagon has never acknowledged the juvenile status of Khadr, Jawad or El Gharani. Although international law provides that anyone under 18 is a child and entitled to special treatment, the Defense Department created its own standard: Anyone who was 16 would automatically be treated as an adult. When I asked Defense Department officials in 2004 about the rationale for this policy, they had no reply. One official finally admitted to me that it was completely arbitrary.

During last week's hearing, Frakt, Jawad's attorney, asked the prosecutor who authorized the charges against Jawad: "You did not believe his age was worthy of bringing to the attention of the convening authority?" Lt. Col. William Britt's answer: "No, I didn't."

The Bush administration's refusal to treat these prisoners as juveniles has had profound consequences for Khadr, Jawad and El-Gharani. They have had no access to education or recreation facilities and have been housed in the same facilities as adult detainees. After five years of imprisonment, Jawad remains functionally illiterate. None of the three have been allowed to see members of their family.

The effects of prolonged isolation have taken a severe toll. El Gharani has tried to commit suicide at least seven times. He has slit his wrist, run repeatedly into the sides of his cell and tried to hang himself. On several occasions he has been placed on suicide watch in a mental health unit.

Jawad also tried to commit suicide about 11 months after arriving in Guantánamo, by hanging himself by his shirt collar. Prison records also state that he "attempted self-harm by banging his head off of metal structures inside his cell."

On the witness stand last week Jawad referred to his suicide attempt. "Islam never permits [suicide], but when a person is in great trouble, it was beyond my control. That's why I tried that." His lawyer says that Jawad seems to have lost touch with reality and suffers from major depression.

At O'Kelley's bar, an incongruous Irish pub at the naval base here, journalists, defense lawyers and human rights observers gather to talk about the bizarre world of Guantánamo. I've heard people express disbelief repeatedly that although the United States has detained nearly 700 suspects at Guantánamo since its inception, it has singled out two juveniles to be among the first detainees prosecuted under the military commissions. Officials associated with the military commissions have suggested that the youths’ alleged direct attacks on U.S. soldiers would "capture the imagination" of the American public.

Strikingly, it was just around the time that Khadr, El Gharani and Jawad were transferred to Guantánamo that the U.S. ratified an international treaty barring the use of children under 18 in armed conflict. The treaty also obligates governments to help rehabilitate child soldiers and help them reintegrate into society.

In some respects, the U.S. has taken its new responsibilities seriously: Each branch of the armed forces adopted new policies to keep American military personnel out of combat until they reach age 18 and to delay deployment of 17-year-old volunteers. Since 2001, the U.S. has also contributed more than $34 million around the globe to prevent the recruitment and use of child soldiers and to demobilize and reintegrate child combatants. Since 2003, $4.5 million in U.S. funds has supported a demobilization program for over 5,000 former child soldiers in Afghanistan.

The commitment to rehabilitation, however, seems to be missing in action when child soldiers engaging U.S. forces are captured.

Khadr's attorneys argued at Guantánamo in February that as a former child soldier, Khadr should not be tried before a military commission. They claimed that international law obligates the U.S. to treat Khadr as a victim, not to punish him, and that Congress did not give the military tribunals jurisdiction over crimes by juveniles. The military judge rejected their motion.

As the proceedings move forward the U.S. continues to turn a blind eye to Khadr's juvenile status. Recently, his attorneys requested funding to secure a child psychologist and psychiatrist as expert witnesses at Khadr's trial. Those requests also were denied.

International law does not preclude the possibility of prosecuting former child soldiers for serious criminal offenses. But the standards are very clear: Such cases should be handled as quickly as possible through specialized juvenile justice systems. Rehabilitation must be the primary objective, and conditions of detention must include access to family, education, recreation and other special assistance.

On every count, the U.S. has failed at Guantánamo to meet these requirements.

The judge in Khadr's case announced last week that Khadr's trial would begin on October 8. Even if acquitted, however, the U.S. government has said that it may continue to detain him "in order to mitigate the threat posed by the detainee."

Jawad's hearings will resume in August.

El Gharani has not been charged, and spends his days languishing in a cell with little more than a mattress, a copy of the Quran and toilet paper.

Shares