The last several years have brought a parade of dark revelations about the George W. Bush administration, from the manipulation of intelligence to torture to extrajudicial spying inside the United States. But there are growing indications that these known abuses of power may only be the tip of the iceberg. Now, in the twilight of the Bush presidency, a movement is stirring in Washington for a sweeping new inquiry into White House malfeasance that would be modeled after the famous Church Committee congressional investigation of the 1970s.

While reporting on domestic surveillance under Bush, Salon obtained a detailed memo proposing such an inquiry, and spoke with several sources involved in recent discussions around it on Capitol Hill. The memo was written by a former senior member of the original Church Committee; the discussions have included aides to top House Democrats, including Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Judiciary Committee chairman John Conyers, and until now have not been disclosed publicly.

Salon has also uncovered further indications of far-reaching and possibly illegal surveillance conducted by the National Security Agency inside the United States under President Bush. That includes the alleged use of a top-secret, sophisticated database system for monitoring people considered to be a threat to national security. It also includes signs of the NSA's working closely with other U.S. government agencies to track financial transactions domestically as well as globally.

The proposal for a Church Committee-style investigation emerged from talks between civil liberties advocates and aides to Democratic leaders in Congress, according to sources involved. (Pelosi's and Conyers' offices both declined to comment.) Looking forward to 2009, when both Congress and the White House may well be controlled by Democrats, the idea is to have Congress appoint an investigative body to discover the full extent of what the Bush White House did in the war on terror to undermine the Constitution and U.S. and international laws. The goal would be to implement government reforms aimed at preventing future abuses -- and perhaps to bring accountability for wrongdoing by Bush officials.

"If we know this much about torture, rendition, secret prisons and warrantless wiretapping despite the administration's attempts to stonewall, then imagine what we don't know," says a senior Democratic congressional aide who is familiar with the proposal and has been involved in several high-profile congressional investigations.

"You have to go back to the McCarthy era to find this level of abuse," says Barry Steinhardt, the director of the Program on Technology and Liberty for the American Civil Liberties Union. "Because the Bush administration has been so opaque, we don't know [the extent of] what laws have been violated."

The parameters for an investigation were outlined in a seven-page memo, written after the former member of the Church Committee met for discussions with the ACLU, the Center for Democracy and Technology, Common Cause and other watchdog groups. Key issues to investigate, those involved say, would include the National Security Agency's domestic surveillance activities; the Central Intelligence Agency's use of extraordinary rendition and torture against terrorist suspects; and the U.S. government's extensive use of military assets -- including satellites, Pentagon intelligence agencies and U2 surveillance planes -- for a vast spying apparatus that could be used against the American people.

Specifically, the ACLU and other groups want to know how the NSA's use of databases and data mining may have meshed with other domestic intelligence activities, such as the U.S. government's extensive use of no-fly lists and the Treasury Department's list of "specially designated global terrorists" to identify potential suspects. As of mid-July, says Steinhardt, the no-fly list includes more than 1 million records corresponding to more than 400,000 names. If those people really represent terrorist threats, he says, "our cities would be ablaze." A deeper investigation into intelligence abuses should focus on how these lists feed on each other, Steinhardt says, as well as the government's "inexorable trend towards treating everyone as a suspect."

"It's not just the 'Terrorist Surveillance Program,'" agrees Gregory T. Nojeim from the Center for Democracy and Technology, referring to the Bush administration's misleading name for the NSA's warrantless wiretapping program. "We need a broad investigation on the way all the moving parts fit together. It seems like we're always looking at little chunks and missing the big picture."

A prime area of inquiry for a sweeping new investigation would be the Bush administration's alleged use of a top-secret database to guide its domestic surveillance. Dating back to the 1980s and known to government insiders as "Main Core," the database reportedly collects and stores -- without warrants or court orders -- the names and detailed data of Americans considered to be threats to national security.

According to several former U.S. government officials with extensive knowledge of intelligence operations, Main Core in its current incarnation apparently contains a vast amount of personal data on Americans, including NSA intercepts of bank and credit card transactions and the results of surveillance efforts by the FBI, the CIA and other agencies. One former intelligence official described Main Core as "an emergency internal security database system" designed for use by the military in the event of a national catastrophe, a suspension of the Constitution or the imposition of martial law. Its name, he says, is derived from the fact that it contains "copies of the 'main core' or essence of each item of intelligence information on Americans produced by the FBI and the other agencies of the U.S. intelligence community."

Some of the former U.S. officials interviewed, although they have no direct knowledge of the issue, said they believe that Main Core may have been used by the NSA to determine who to spy on in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. Moreover, the NSA's use of the database, they say, may have triggered the now-famous March 2004 confrontation between the White House and the Justice Department that nearly led Attorney General John Ashcroft, FBI director William Mueller and other top Justice officials to resign en masse.

The Justice Department officials who objected to the legal basis for the surveillance program -- former Deputy Attorney General James B. Comey and Jack Goldsmith, the former head of the Office of Legal Counsel -- testified before Congress last year about the 2004 showdown with the White House. Although they refused to discuss the highly classified details behind their concerns, the New York Times later reported that they were objecting to a program that "involved computer searches through massive electronic databases" containing "records of the phone calls and e-mail messages of millions of Americans."

According to William Hamilton, a former NSA intelligence officer who left the agency in the 1970s, that description sounded a lot like Main Core, which he first heard about in detail in 1992. Hamilton, who is the president of Inslaw Inc., a computer services firm with many clients in government and the private sector, says there are strong indications that the Bush administration's domestic surveillance operations use Main Core.

Hamilton's company Inslaw is widely respected in the law enforcement community for creating a program called the Prosecutors' Management Information System, or PROMIS. It keeps track of criminal investigations through a powerful search engine that can quickly access all stored data components of a case, from the name of the initial investigators to the telephone numbers of key suspects. PROMIS, also widely used in the insurance industry, can also sort through other databases fast, with results showing up almost instantly. "It operates just like Google," Hamilton told me in an interview in his Washington office in May.

Since the late 1980s, Inslaw has been involved in a legal dispute over its claim that Justice Department officials in the Reagan administration appropriated the PROMIS software. Hamilton claims that Reagan officials gave PROMIS to the NSA and the CIA, which then adapted the software -- and its outstanding ability to search other databases -- to manage intelligence operations and track financial transactions. Over the years, Hamilton has employed prominent lawyers to pursue the case, including Elliot Richardson, the former attorney general and secretary of defense who died in 1999, and C. Boyden Gray, the former White House counsel to President George H.W. Bush. The dispute has never been settled. But based on the long-running case, Hamilton says he believes U.S. intelligence uses PROMIS as the primary software for searching the Main Core database.

Hamilton was first told about the connection between PROMIS and Main Core in the spring of 1992 by a U.S. intelligence official, and again in 1995 by a former NSA official. In July 2001, Hamilton says, he discussed his case with retired Adm. Dan Murphy, a former military advisor to Elliot Richardson who later served under President George H.W. Bush as deputy director of the CIA. Murphy, who died shortly after his meeting with Hamilton, did not specifically mention Main Core. But he informed Hamilton that the NSA's use of PROMIS involved something "so seriously wrong that money alone cannot cure the problem," Hamilton told me. He added, "I believe in retrospect that Murphy was alluding to Main Core." Hamilton also provided copies of letters that Richardson and Gray sent to U.S. intelligence officials and the Justice Department on Inslaw's behalf alleging that the NSA and the CIA had appropriated PROMIS for intelligence use.

Hamilton says James B. Comey's congressional testimony in May 2007, in which he described a hospitalized John Ashcroft's dramatic standoff with senior Bush officials Alberto Gonzales and Andrew Card, was another illuminating moment. "It was then that we [at Inslaw] started hearing again about the Main Core derivative of PROMIS for spying on Americans," he told me.

Through a former senior Justice Department official with more than 25 years of government experience, Salon has learned of a high-level former national security official who reportedly has firsthand knowledge of the U.S. government's use of Main Core. The official worked as a senior intelligence analyst for a large domestic law enforcement agency inside the Bush White House. He would not agree to an interview. But according to the former Justice Department official, the former intelligence analyst told her that while stationed at the White House after the 9/11 attacks, one day he accidentally walked into a restricted room and came across a computer system that was logged on to what he recognized to be the Main Core database. When she mentioned the specific name of the top-secret system during their conversation, she recalled, "he turned white as a sheet."

An article in Radar magazine in May, citing three unnamed former government officials, reported that "8 million Americans are now listed in Main Core as potentially suspect" and, in the event of a national emergency, "could be subject to everything from heightened surveillance and tracking to direct questioning and even detention."

The alleged use of Main Core by the Bush administration for surveillance, if confirmed to be true, would indicate a much deeper level of secretive government intrusion into Americans' lives than has been previously known. With respect to civil liberties, says the ACLU's Steinhardt, it would be "pretty frightening stuff."

The Inslaw case also points to what may be an extensive role played by the NSA in financial spying inside the United States. According to reports over the years in the U.S. and foreign press, Inslaw's PROMIS software was embedded surreptitiously in systems sold to foreign and global banks as a way to give the NSA secret "backdoor" access to the electronic flow of money around the world.

In May, I interviewed Norman Bailey, a private financial consultant with years of government intelligence experience dating from the George W. Bush administration back to the Reagan administration. According to Bailey -- who from 2006 to 2007 headed a special unit within the Office of the Director of National Intelligence focused on financial intelligence on Cuba and Venezuela -- the NSA has been using its vast powers with signals intelligence to track financial transactions around the world since the early 1980s.

From 1982 to 1984, Bailey ran a top-secret program for President Reagan's National Security Council, called "Follow the Money," that used NSA signals intelligence to track loans from Western banks to the Soviet Union and its allies. PROMIS, he told me, was "the principal software element" used by the NSA and the Treasury Department then in their electronic surveillance programs tracking financial flows to the Soviet bloc, organized crime and terrorist groups. His admission is the first public acknowledgement by a former U.S. intelligence official that the NSA used the PROMIS software.

According to Bailey, the Reagan program marked a significant shift in resources from human spying to electronic surveillance, as a way to track money flows to suspected criminals and American enemies. "That was the beginning of the whole process," he said.

After 9/11, this capability was instantly seen within the U.S. government as a critical tool in the war on terror -- and apparently was deployed by the Bush administration inside the United States, in cases involving alleged terrorist supporters. One such case was that of the Al-Haramain Islamic Foundation in Oregon, which was accused of having terrorist ties after the NSA, at the request of the Treasury Department, eavesdropped on the phone calls of Al-Haramain officials and their American lawyers. The charges against Al-Haramain were based primarily on secret evidence that the Bush administration refused to disclose in legal proceedings; Al-Haramain's lawyers argued in a lawsuit that was a violation of the defendants' due process rights.

According to Bailey, the NSA also likely would have used its technological capabilities to track the charity's financial activity. "The vast majority of financial movements of any significance take place electronically, so intercepts have become an extremely important element" in intelligence, he explained. "If the government suspects that a particular Muslim charitable organization is engaged in collecting funds to funnel to terrorists, the NSA would be asked to follow the money going into and out of the bank accounts of that charity." (The now-defunct Al-Haramain Foundation, although affiliated with a Saudi Arabian-based global charity, was founded and based in Ashland, Ore.)

The use of a powerful database and extensive watch lists, Bailey said, would make the NSA's job much easier. "The biggest problems with intercepts, quite frankly, is that the volumes of data, daily or even by the hour, are gigantic," he said. "Unless you have a very precise idea of what it is you're looking for, the NSA people or their counterparts [overseas] will just throw up their hands and say 'forget it.'" Regarding domestic surveillance, Bailey said there's a "whole gray area where the initiation of the transaction was in the United States and the final destination was outside, or vice versa. That's something for the lawyers to figure out."

Bailey's information on the evolution of the Reagan intelligence program appears to corroborate and clarify an article published in March in the Wall Street Journal, which reported that the NSA was conducting domestic surveillance using "an ad-hoc collection of so-called 'black programs' whose existence is undisclosed." Some of these programs began "years before the 9/11 attacks but have since been given greater reach." Among them, the article said, are a joint NSA-Treasury database on financial transactions that dates back "about 15 years" to 1993. That's not quite right, Bailey clarified: "It started in the early '80s, at least 10 years before."

Main Core may be the contemporary incarnation of a government watch list system that was part of a highly classified "Continuity of Government" program created by the Reagan administration to keep the U.S. government functioning in the event of a nuclear attack. Under a 1982 presidential directive, the outbreak of war could trigger the proclamation of martial law nationwide, giving the military the authority to use its domestic database to round up citizens and residents considered to be threats to national security. The emergency measures for domestic security were to be carried out by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Army.

In the late 1980s, reports about a domestic database linked to FEMA and the Continuity of Government program began to appear in the press. For example, in 1986 the Austin American-Statesman uncovered evidence of a large database that authorities were proposing to use to intern Latino dissidents and refugees during a national emergency that might follow a potential U.S. invasion of Nicaragua. During the Iran-Contra congressional hearings in 1987, questions to Reagan aide Oliver North about the database were ruled out of order by the committee chairman, Democratic Sen. Daniel Inouye, because of the "highly sensitive and classified" nature of FEMA's domestic security operations.

In September 2001, according to "The Rise of the Vulcans," a 2004 book on Bush's war cabinet by James Mann, a contemporary version of the Continuity of Government program was put into play in the hours after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, when Vice President Cheney and senior members of Congress were dispersed to "undisclosed locations" to maintain government functions. It was during this emergency period, Hamilton and other former government officials believe, that President Bush may have authorized the NSA to begin actively using the Main Core database for domestic surveillance. One indicator they cite is a statement by Bush in December 2005, after the New York Times had revealed the NSA's warrantless wiretapping, in which he made a rare reference to the emergency program: The Justice Department's legal reviews of the NSA activity, Bush said, were based on "fresh intelligence assessment of terrorist threats to the continuity of our government."

It is noteworthy that two key players on Bush's national security team, Cheney and his chief of staff, David Addington, have been involved in the Continuity of Government program since its inception. Along with Donald Rumsfeld, Bush's first secretary of defense, both men took part in simulated drills for the program during the 1980s and early 1990s. Addington's role was disclosed in "The Dark Side," a book published this month about the Bush administration's war on terror by New Yorker reporter Jane Mayer. In the book, Mayer calls Addington "the father of the [NSA] eavesdropping program," and reports that he was the key figure involved in the 2004 dispute between the White House and the Justice Department over the legality of the program. That would seem to make him a prime witness for a broader investigation.

Getting a full picture on Bush's intelligence programs, however, will almost certainly require any sweeping new investigation to have a scope that would inoculate it against charges of partisanship. During one recent discussion on Capitol Hill, according to a participant, a senior aide to Speaker Pelosi was asked for Pelosi's views on a proposal to expand the investigation to past administrations, including those of Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush. "The question was, how far back in time would we have to go to make this credible?" the participant in the meeting recalled.

That question was answered in the seven-page memo. "The rise of the 'surveillance state' driven by new technologies and the demands of counter-terrorism did not begin with this Administration," the author wrote. Even though he acknowledged in interviews with Salon that the scope of abuse under George W. Bush would likely be an order of magnitude greater than under preceding presidents, he recommended in the memo that any new investigation follow the precedent of the Church Committee and investigate the origins of Bush's programs, going as far back as the Reagan administration.

The proposal has emerged in a political climate reminiscent of the Watergate era. The Church Committee was formed in 1975 in the wake of media reports about illegal spying against American antiwar activists and civil rights leaders, CIA assassination squads, and other dubious activities under Nixon and his predecessors. Chaired by Sen. Frank Church of Idaho, the committee interviewed more than 800 officials and held 21 public hearings. As a result of its work, Congress in 1978 passed the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which required warrants and court supervision for domestic wiretaps, and created intelligence oversight committees in the House and Senate.

So far, no lawmaker has openly endorsed a proposal for a new Church Committee-style investigation. A spokesman for Pelosi declined to say whether Pelosi herself would be in favor of a broader probe into U.S. intelligence. On the Senate side, the most logical supporters for a broader probe would be Democratic senators such as Patrick Leahy of Vermont and Russ Feingold of Wisconsin, who led the failed fight against the recent Bush-backed changes to FISA. (Both Feingold and Leahy's offices declined to comment on a broader intelligence inquiry.)

The Democrats' reticence on such action ultimately may be rooted in congressional complicity with the Bush administration's intelligence policies. Many of the war on terror programs, including the NSA's warrantless surveillance and the use of "enhanced interrogation techniques," were cleared with key congressional Democrats, including Pelosi, Senate Intelligence Committee chairman Rockefeller, and former House Intelligence chairwoman Jane Harman, among others.

The discussions about a broad investigation were jump-started among civil liberties advocates this spring, when it became clear that the Democrats didn't have the votes to oppose the Bush-backed bill updating FISA. The new legislation could prevent the full story of the NSA surveillance programs from ever being uncovered; it included retroactive immunity for telecommunications companies that may have violated FISA by collaborating with the NSA on warrantless wiretapping. Opponents of Bush's policies were further angered when Democratic leaders stripped from their competing FISA bill a provision that would have established a national commission to investigate post-9/11 surveillance programs.

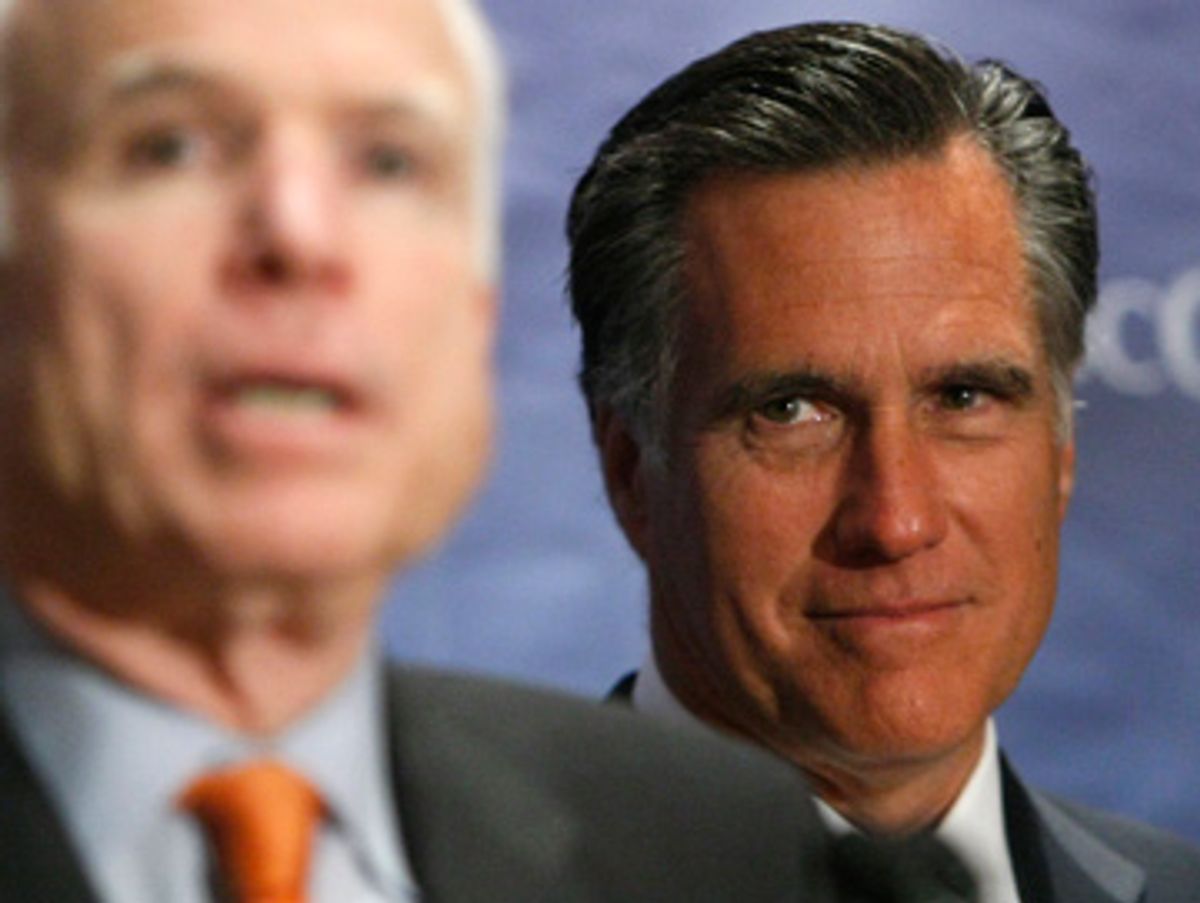

The next president obviously would play a key role in any decision to investigate intelligence abuses. Sen. John McCain, the Republican candidate, is running as a champion of Bush's national security policies and would be unlikely to embrace an investigation that would, foremost, embarrass his own party. (Randy Scheunemann, McCain's spokesman on national security, declined to comment.)

Some see a brighter prospect in Barack Obama, should he be elected. The plus with Obama, says the former Church Committee staffer, is that as a proponent of open government, he could order the executive branch to be more cooperative with Congress, rolling back the obsessive secrecy and stonewalling of the Bush White House. That could open the door to greater congressional scrutiny and oversight of the intelligence community, since the legislative branch lacked any real teeth under Bush. (Obama's spokesman on national security, Ben Rhodes, did not reply to telephone calls and e-mails seeking comment.)

But even that may be a lofty hope. "It may be the last thing a new president would want to do," said a participant in the ongoing discussions. Unfortunately, he said, "some people see the Church Committee ideas as a substitute for prosecutions that should already have happened."

Shares