"I've had my fill of partisan excesses, and I don't intend to disgrace myself by indulging in them." -- "Worth the Fighting For," by John McCain with Mark Salter (2002)

The driving narrative of John McCain's political career is not enduring five and a half years in a POW camp, but suffering through four years in the cross hairs of a late 1980s congressional scandal known as the Keating Five. As McCain tells it (and he has discussed it in almost every medium aside from Japanese manga comics), this was a classic tale of sin and salvation as an erring senator makes a grievous mistake in judgment, is hauled before the Senate Ethics Committee and, as a result, is forever changed by the public humiliation.

"I would very much like to think that I have never been a man whose favor could be bought. From my earliest youth, I would have considered such a reputation to be the most shameful ignominy imaginable," McCain writes in his 2002 memoir. "Yet that is exactly how millions of Americans viewed me for a time, a time that I will forever consider one of the worst experiences of my life." (For those who lack an encyclopedic memory of 1988 news headlines, McCain, along with four other Democratic senators, improperly intervened with federal regulators in an effort to save the crumbling savings-and-loan empire of Charles Keating, an Arizona friend and campaign contributor of McCain's.)

The Keating Five have long hovered on the periphery of the 2008 campaign as a blast-from-the-past partisan talking point -- a bit like Joe Biden's 1987 burst of plagiarism when he lifted the hardscrabble family history of British politician Neil Kinnock and passed it off as his own. Twenty years is a long time for penance, and most voters seemed willing to abide by a statute of limitations about scandals that date back to the era of phone booths and boom boxes.

But all that changed on Ski-Slope Monday when the minute-by-minute chart of the Dow Jones Average looked like a plunge off a mountain. (When everyone is breathing a sigh of relief because the Dow rallied near the close to only be down 370 points, you get a sense of how brutal the fiscal carnage was.) Confronted with America's incredible shrinking stock portfolio, both the McCain and Obama campaigns reacted with the maturity that the financial crisis deserves. McCain and Sarah Palin tried to foster the impression that, if elected, Obama would name 1960s radical Bill Ayers to head the newly created Department of Molotov Cocktails. And the Obama campaign countered by releasing a searing video titled "Keating Economics."

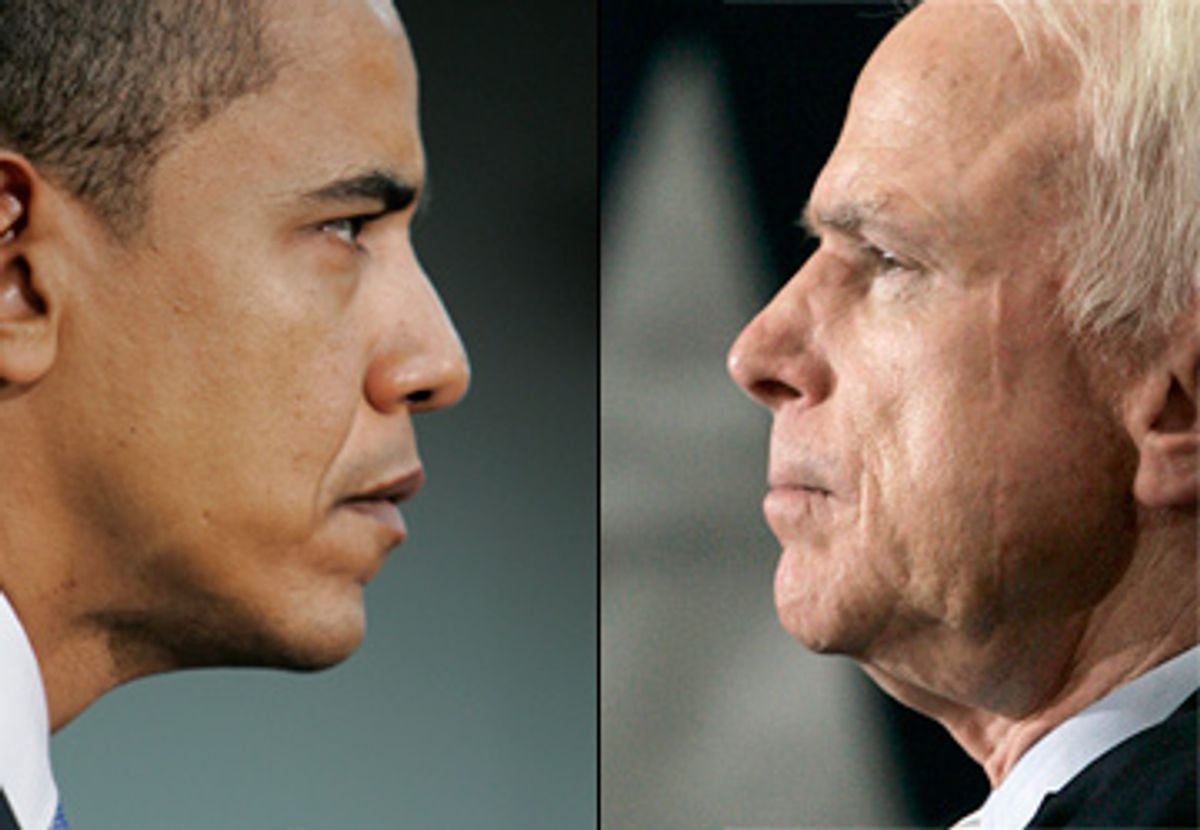

This was, in short, a day in which it seemed like both campaigns were conspiring to prove to a skeptical world that America is not ready for self-government. Instead of retreating to their respective debate camps to practice their spontaneous one-liners and empathetic gestures (Tuesday night's Nashville Knockdown will employ a town-meeting format moderated by Tom Brokaw), McCain and Obama were mired in the politics of irrelevancy. The political strategies on both sides are nakedly apparent -- McCain desperately needs to discredit Obama, since he cannot survive an election where the dominant topics are recession, Wall Street and George W. Bush. And Obama -- chastened by Democratic docility in the face of GOP attacks -- has vowed from the outset to run an Old Testament campaign based on the uplifting principle of "an eye for an eye."

Ayers, to be sure, was always a peripheral figure in Obama's universe. As the New York Times pointed out in a detailed look at the Ayers-Obama question, "Since 2002, there is little public evidence of their relationship." But Obama clearly exaggerated during the primaries when he dismissed Ayers as merely "a guy who lives in my neighborhood," since the two men served together on the seven-member board of the Woods Fund, a Chicago charity, for two years.

[A point of personal indulgence: I, too, can claim knowing Ayers as a guy from the neighborhood, since we overlapped on the University of Michigan campus in the late 1960s. I recall running into Ayers -- who was in the midst of helping form the violent wing of SDS known as the "Weathermen" -- in Ann Arbor, a few days before the 1968 Democratic convention. "Hey, man, are you going to Chicago for the convention?" he asked. "No," I replied, "they're going to nominate [Hubert] Humphrey, so why bother?" Then Ayers offered me a news tip that I foolishly ignored: "There's going to be great shit happening in the streets. You've got to go."]

On this day of tit-for-tat politics, the Obama campaign missed the real reason why the Keating Five remain relevant 20 years later. The point lies not in the details of the bygone scandal (trust me, they are complex and murky), but in the way that McCain has abandoned in this presidential campaign all the good-government habits that he adopted after he was chastised by the Ethics Committee. As he recounted in his memoir, "I decided right then that not talking to reporters or sharply denying even the appearance of a problem wasn't going to do me any good. I would henceforth accept every single request for an interview ... and answer every question as completely and straightforwardly as I could."

McCain, who until the spring was indeed the most accessible major politician in America, has veered completely in the other direction, avoiding reporters at one point for more than a month. As the decider on the Republican ticket, McCain is also responsible for the Arctic-chill media strategy that has almost completely muzzled Sarah Palin since her selection as his running mate.

Far more disturbing is that it has become difficult to believe that John McCain recalls the larger lessons about personal honor that he supposedly carried away from his Keating Five disgrace. As the campaign to tarnish Obama grows brutish and ugly (and there are still four weeks left for subterranean tactics), it seems apparent that McCain has made a Faustian bargain to try to win the White House. If successful, McCain, of course, will have power. But if he fails, he will only have his regrets and his late-in-life reputation for low-road tactics.

Shares