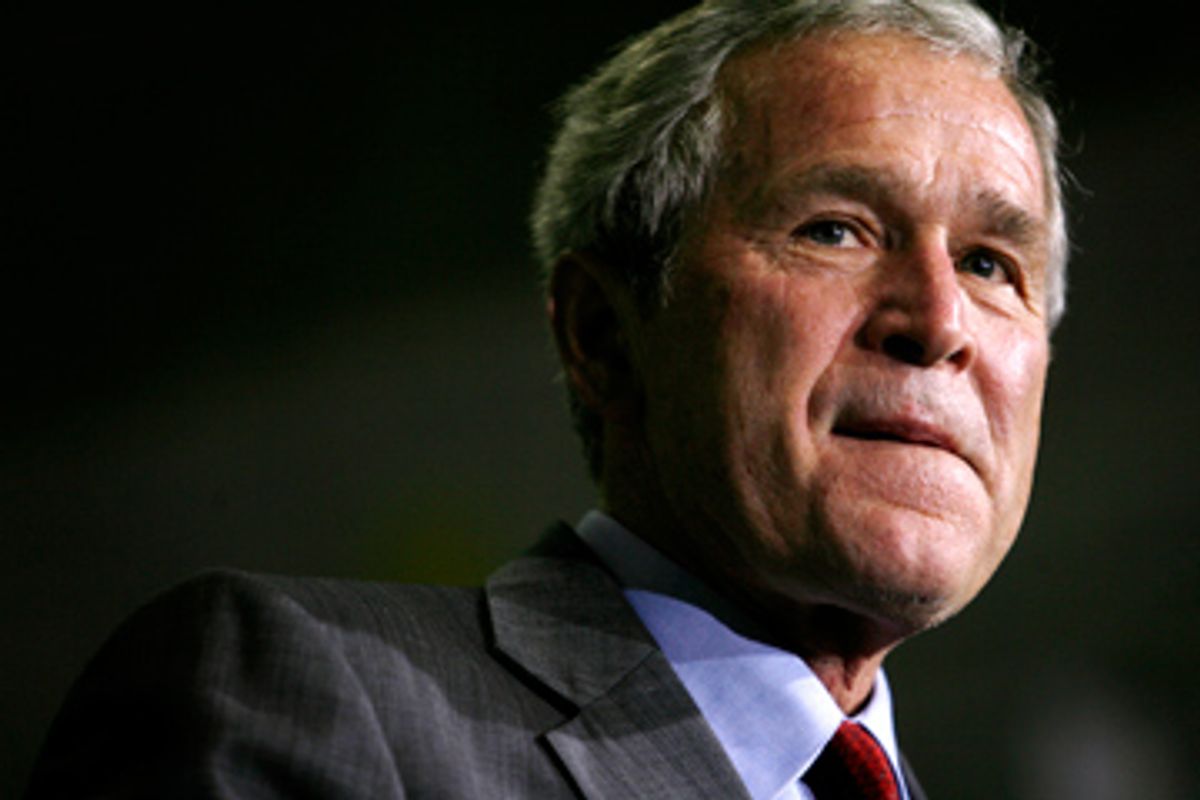

With growing talk in Washington that President Bush may be considering an unprecedented "blanket pardon" for people involved in his administration's brutal interrogation policies, advisors to Barack Obama are pressing ahead with plans for a nonpartisan commission to investigate alleged abuses under Bush.

The Obama plan, first revealed by Salon in August, would emphasize fact-finding investigation over prosecution. It is gaining currency in Washington as Obama advisors begin to coordinate with Democrats in Congress on the proposal. The plan would not rule out future prosecutions, but would delay a decision on that matter until all essential facts can be unearthed. Between the time necessary for the investigative process and the daunting array of policy problems Obama will face upon taking office, any decision on prosecutions probably would not come until a second Obama presidential term, should there be one.

The proposed commission -- similar in thrust to a Democratic investigation proposal first uncovered by Salon in July -- would examine a broad scope of activities, including detention, torture and extraordinary rendition, the practice of snatching suspected terrorists off the street and whisking them off to a third country for abusive interrogations. The commission might also pry into the claims by the White House -- widely rejected by experienced interrogators -- that abusive interrogations are an effective and necessary intelligence tool.

A common view among those involved with the talks is that any early effort to prosecute Bush administration officials would likely devolve quickly into ugly and fruitless partisan warfare. Second is that even if Obama decided he had the appetite for it, prosecutions in this arena are problematic at best: A series of memos from the Bush Justice Department approved the harsh tactics, and Congress changed the War Crimes Act in 2006, making prosecutions of individuals involved in interrogations more difficult.

Instead, a commission empowered by Congress would have the authority to compel witnesses to testify and even to grant immunity in exchange for information. Should a particularly ugly picture emerge, the option of prosecutions would still theoretically be on the table later, however unlikely.

In Obama's camp, there is a sense among some that such a commission would essentially mean letting Bush get away with crimes. "People have called for criminal investigations," one person familiar with the talks told me this summer as plans got under way. On Wednesday, a person participating in the talks confirmed that some people involved in the planning felt strongly that the commission would amount to "bullshit" and that Bush officials should be prosecuted to the full extent of the law.

But few think prosecutions are realistic, given the formidable legal hurdles and the huge policy problems competing for Obama's attention. Among them is the complicated task of closing down the military prison at Guantánamo Bay, which Obama advisors say is a priority. Some observers outside the Obama camp are also questioning how much Democrats really want exposed with regard to interrogation, since top Democrats in Congress were briefed in secret on some of the harshest tactics used by the CIA and appear to have done little, or perhaps nothing, to stop them.

Further complicating the Obama team's planning is uncertainty about what President Bush might do. On the one hand, a blanket pardon for anyone involved in the interrogations could be viewed by the public as a tacit admission of colossal wrongdoing -- after years of public denial -- which would do nothing to help Bush's tarnished legacy. Yet, if the administration fears an investigation will follow Bush out the door in January, they may not want to leave officials exposed to potentially revealing criminal proceedings. Bush might seek to frame a blanket pardon as a preemptive strike against wrongheaded, partisan retribution.

Constitutional scholars say a pardon of this kind would be an unprecedented move -- the prospective pardon of not just individuals but entire categories of people, perhaps numbering in the thousands, for carrying out the president's orders , which the White House has argued all along were legal.

Those scholars agree, however, that Article II of the Constitution gives Bush much latitude: There is no authority that can stop the president from doing so if he wishes, and there is no outside check or balance to revisit such a decision, however controversial it may be. "The president can do with pardoning power whatever he wants," explained University of Wisconsin Law School professor Stanley Kutler. "It is complete and plenary unto itself."

A blanket pardon from Bush could cover, for example, anyone who participated in, had knowledge of, or received information about Bush's interrogation program during the so-called war on terror. Not only are there potentially too many people to name without risking missing somebody, but some of the names are presumably classified.

"The classic pardon is an identifiable individual; here you are talking about potentially thousands of people involved in illegal activities," explained Jonathan Turley, a professor at George Washington Law School. A blanket pardon of this variety, Turley said, "would allow a president to engage in massive illegality and generally pardon the world for any involvement in unlawful activity."

There are, in fact, some constitutional scholars who believe a pardon might actually facilitate more complete participation in a fact-finding commission, by removing the threat of looming liability. "Holding people accountable is certainly nice, but in terms of healing the country and moving forward, so is actually getting a clear picture of what happened and letting the public make an informed decision," said Kermit Roosevelt at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. "If we had a pardon followed by something like a truth and reconciliation commission, that might not be such a bad outcome." (Roosevelt represents a detainee held at Guantánamo.)

The politics of it would be fraught with danger, however, and could so blemish Bush's legacy that some doubt he would go so far. "A pardon is an admission of guilt," noted Donald Kettl, a political science professor at the University of Pennsylvania. Bush has argued for years that his interrogation program was perfectly legal. With a pardon, Kettl said, Bush is essentially saying, "Gee, maybe we did not do the right thing."

It is not entirely unprecedented for a president to grant a pardon based on a category of behavior, rather than pardoning an individual by name. The day after his inauguration, President Carter pardoned all those who avoided the Vietnam draft by failing to register or by fleeing to Canada. George Washington pardoned participants in the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion. Andrew Johnson pardoned Confederate soldiers in 1865.

But these were pardons designed to foster reconciliation, handed out to categories of individuals who acted on their own conscience, rather than the president's own allegedly illegal orders. "This would be a different deal completely," explained Kettl. "It would be anticipating that people thought the official policy of the administration was wrong."

Shares