As President Obama walked to the East Room of the White House Thursday morning for what was billed as an "experimental" online town hall meeting, aides passed him a message. The 3.6 million votes cast on the 104,000 questions people had submitted on the government's site had yielded a bit of a surprise: The most popular questions in several categories (including "financial stability" and, predictably enough, "green jobs") asked not about the economic collapse or about healthcare, but about legalizing marijuana. But don't worry, the president was told, the event's moderator, administration economist Jared Bernstein, wouldn't be asking any of them.

That apparently didn't strike Obama as being quite as wise as it did the aides in charge of selecting the otherwise on-message questions he took at the event. So midway through, he ventured off the script. "I have to say that there was one question that was voted on that ranked fairly high and that was whether legalizing marijuana would improve the economy and job creation," Obama said, as Bernstein laughed over in the corner of the room. "And I don't know what this says about the online audience, but I just want -- I don't want people to think that -- this was a fairly popular question; we want to make sure that it was answered. The answer is, no, I don't think that is a good strategy to grow our economy." Blowing the question off with a joke probably irritated legalization activists more than ignoring their organized campaign would have, but it did mean the town hall was assured of at least one groundbreaking moment: For the first time ever, the president of the United States called his own supporters a bunch of stoners.

The rest of the morning may have sounded familiar to anyone who watched Obama's mostly news-free news conference Tuesday night or, indeed, to anyone who's watched any of his public appearances since taking office. (Or, for that matter, before then.) Questions touched on education, the economy, the fate of small businesses, healthcare and aid for homeowners. The president explained, early on, why he wanted to try the online format: "Here in Washington, politics all too often is treated like a game. There's a lot of point scoring, a lot of talk about who's up and who's down, a lot of time and energy spent on whether the president is winning or losing on this particular day or this particular hour," he said. "But this isn't about me. It's about you." The town hall -- like the press conference -- was a chance for Obama to talk directly to the public, without the cable news scorekeepers. And it was also an attempt to duplicate the success his campaign found last year by making people feel like they were part of a movement. White House aides said 67,000 people watched the video stream they set up, which isn't bad for the middle of a workday, and nearly 29,000 people had submitted questions as of two hours before the town hall, when aides cut off questions.

On the whole, it was a clever piece of stagecraft by the White House. Aides surrounded Obama with people in the East Room, mostly nurses and teachers from the D.C. area, and turned the question-and-answer session over to the live audience toward the end of the event, which made for better TV than just sticking the president in a room with a laptop. By opening up the questions to the public, aides could claim to be delivering on the transparency Obama promised; by selecting the questions themselves, the administration could ensure that Obama stayed on message. Naturally, the White House emphasized the openness. "In the campaign, you did sort of tend to attract supporters, and here, now that we've opened it up really to anyone to participate, we're seeing some challenging perspectives," Macon Phillips, the White House new media director, told Salon in an interview.

That was true -- up to a point. GOP online strategist Patrick Ruffini had combed through the questions Wednesday, trying to organize Republicans to vote for the ones that might put Obama on the spot. (His effort was unable to dislodge the marijuana questions from the top ranks, which may be the worst sign yet for Republican hopes of a comeback in 2010.) But the questions aides actually selected for Bernstein to read, or to introduce video clips of voters asking on their own, weren't exactly aggressive. "Thank you so much for all your hard work," a video question from a Georgia woman ended. "God bless you."

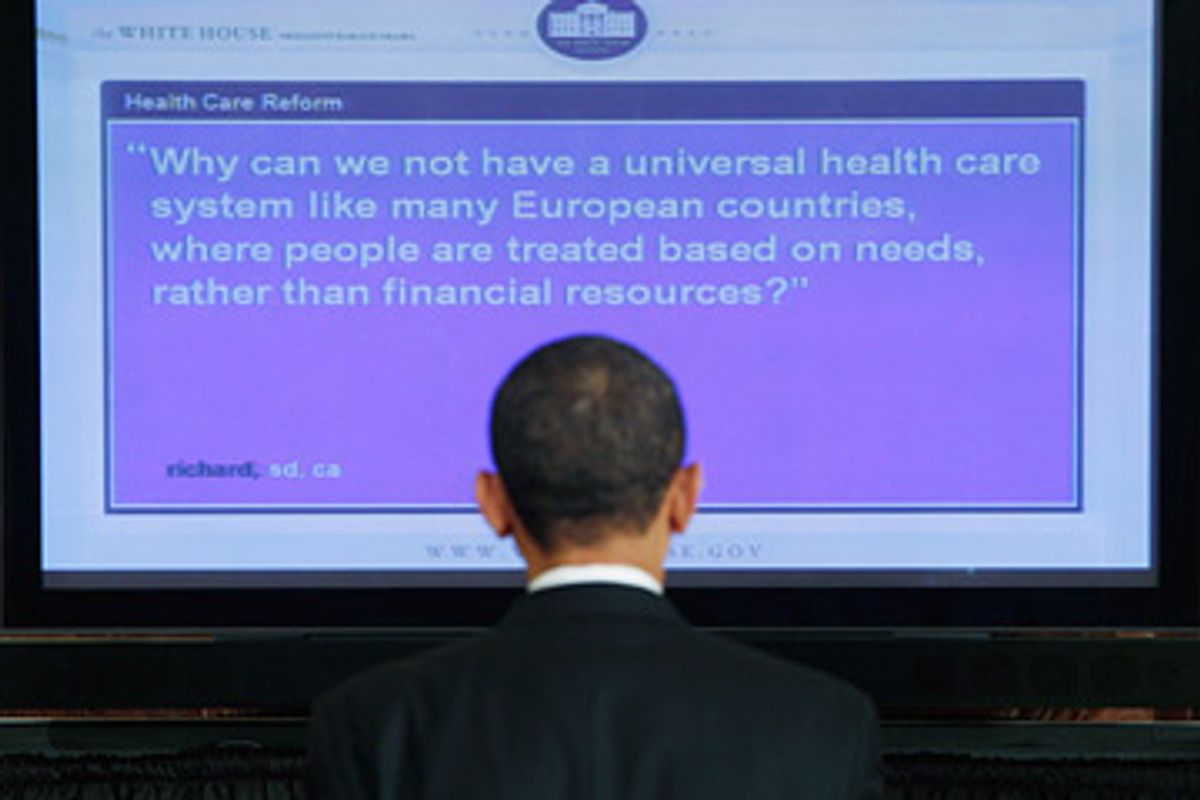

Obama was clearly in his element throughout the event. The president's style at town halls means they frequently seem to bring him back to his days as a law professor, unpacking complex issues in long, detailed answers. He delved into his policies with enough specificity that he had time for only 12 questions -- or 13, counting the pot one he asked himself -- during the hour-plus event. Obama likes to say, in pitching his proposals, that the problems facing America will take complicated, long-term, interconnected solutions. If you didn't already believe he truly felt that way, you might have changed your mind after hearing him take a question on outsourced jobs and, in the course of answering it, give a mini-discourse on the virtues of a solar-powered energy grid. Or explaining, after starting to say he didn't want to go into it, the World War II-era origins of the employer-provided healthcare system he's now trying to fix. His answers showed a savvy about politics, as well as about policy. A question on healthcare, asking why the U.S. didn't move to a European nationalized insurance system, let Obama position his call for universal care as the centrist alternative to some more elaborate Canada-inspired option -- even though there's no chance of passing a reform that sweeping.

And the notion of a virtual town hall must have appealed to the former community organizer in him. "It will take all of us talking with one another, all of us sharing ideas, all of us working together to see our country through this difficult time and bring about that better day," Obama said. He closed with an exhortation to stay involved. "Thanks for paying attention," he told viewers. "And we need you guys to keep paying attention in the months and years to come."

Expect the online town hall to return in the near future. Getting the technical end of things up to speed may be the main impediment. "We have a host of new challenges around deploying technology like this," said Phillips, acknowledging that the government's computer systems aren't anywhere near the standards the campaign got used to last year. "I don't think you're going to see the next [new] thing every two weeks." But very few presidents could resist the chance to beam themselves, and their message, directly to voters, in a way that makes the public feel like a part of the governing process. It may be high-tech, but in the end, online town halls are just a new twist on old-fashioned politics.

Shares