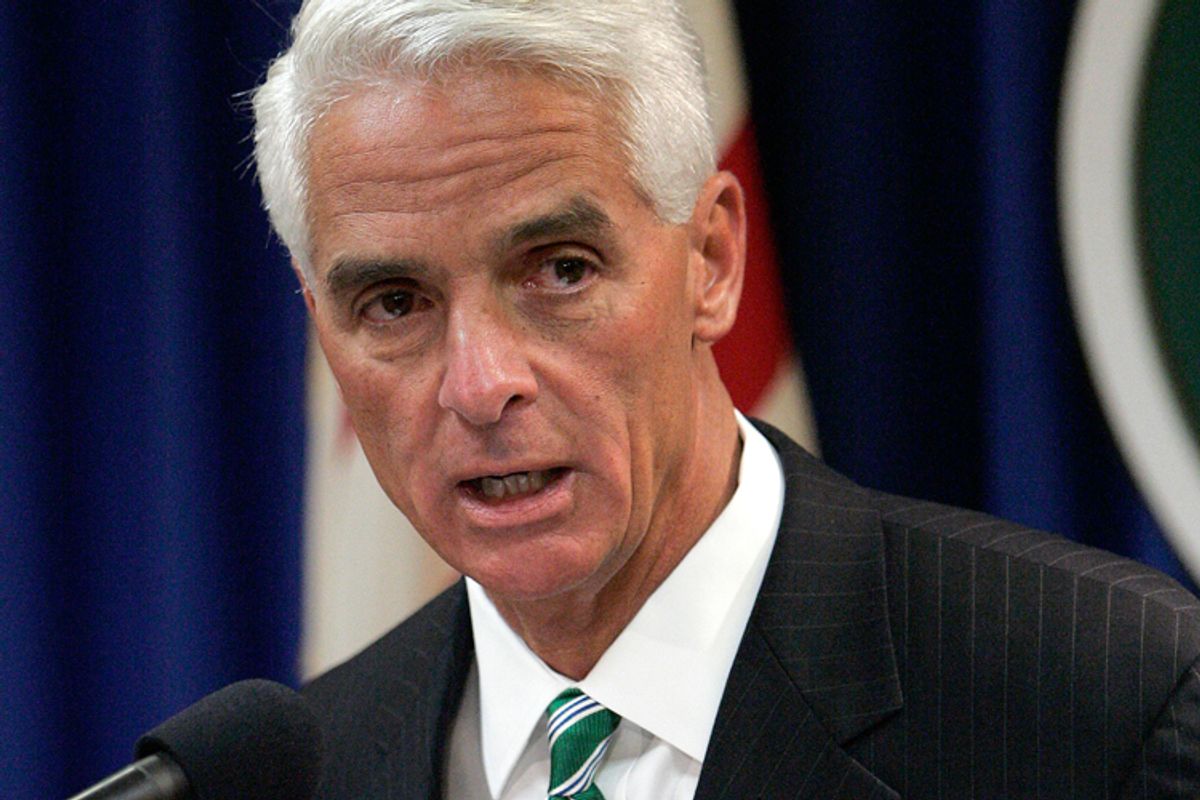

Since Barack Obama's inauguration, the right wing of the Republican Party has mobilized against, among others, Arlen Specter, John McCain, Bob Bennett and Charlie Crist.

The result: Specter left the GOP over a year ago; McCain is facing a grave primary challenge; Bennett may need luck just to make it to a primary in Utah; and Crist is now poised to abandon his GOP primary campaign and run as an independent.

Is this a purge? Absolutely. They've all been targeted for being insufficiently conservative, and the purification campaign doesn't stop with them: Other GOP establishment figures also face potentially serious primary challenges in statewide races across the country.

This isn't as new a phenomenon as you might think. Conservatives have mobilized to cleanse their party of "moderates" before, sometimes with dramatic results.

Perhaps the most notable instance of this came in the late 1970s. The Watergate scandal and the rise of Jimmy Carter in 1976 had rendered the GOP the same depleted party it is today. When the 95th Congress convened in January 1977, Republicans held just 39 Senate seats, the last time until the Obama presidency that one party would enjoy a filibuster-proof majority.

To the right, the GOP's problem was simple: The party hadn't been conservative enough and was overrun by ideological sellouts. In the '76 presidential primaries, Ronald Reagan had come within an inch of swiping the GOP nomination from President Gerald Ford. In the wake of Carter's election, conservative activists decided to launch similar challenges across the country.

So it was that in the 1978 midterm cycle, four-term New Jersey Sen. Clifford Case, a quintessential Northeast moderate, was defeated in the Republican primary by Jeffrey Bell, an obscure 34-year-old Reagan speechwriter. And in Massachusetts, two-term Sen. Ed Brooke barely survived a GOP primary challenge from Avi Nelson, a Boston talk-radio host who'd made his name speaking out against the city's busing program. 1978 was also the year that Maurice Van Nostrand, the favored candidate of Iowa's moderate GOP governor, Bob Ray, was trounced in a GOP Senate primary by Roger Jepsen, the state's right-wing lieutenant governor.

Two years later, when Reagan trounced (then-)moderate George H.W. Bush in the GOP primaries, newly mobilized conservatives helped Alfonse D'Amato knock off Jacob Javits, a Senate icon, in the New York Republican primary. That same year, numerous other conservative Republicans, riding on Reagan's coattails, slipped into office in the fall, giving the GOP Senate control and solidifying the party's embrace of Reagan-style conservatism.

Just like their 1970s forebears, today's conservatives believe their party has been too accommodating of Democrats and their ideas. And, again like the late '70s, their clout within the GOP is particularly pronounced, with the party's ranks thinned by the last two elections.

But there's also a big difference between then and now: The right's definition of a "moderate" has changed considerably.

Thirty years ago, the Republican Party was relatively rich with ideological diversity. Many of the party's elected officials had voting records considerably to the left of those of many Democrats. Javits, for instance, entered Congress in 1947 as a supporter of Harry Truman's agenda, and as a senator voted for LBJ's civil rights and Great Society initiatives. In the 1970s, Case joined with Democrat Frank Church, a liberal stalwart, to author legislation designed to end the Vietnam War. Brooke, the first African-American elected to the Senate after Reconstruction, fought to end discrimination in housing and education.

In this sense, the right's decision to target them -- and others like them -- made perfect sense. The ideological divide between the Javits and Jesse Helms wings of the party was gaping and the GOP's ideological definition was up in the air, so both sides had incentive to duke it out.

But that's not the case today. The issue of the GOP's ideology was settled with Reagan's rise: It's a fundamentally conservative party. Which makes this generation of Republican primary challenges somewhat puzzling. Crist, Bennett and McCain may stray from conservative orthodoxy occasionally, but they are hardly the ideological heretics that Case, Javits and Brooke were. (OK, Specter is a slightly different story, but his example is the exception.) Taking them out might move the party slightly to the right, but unlike the primary challenges of the late '70s, it would do nothing to alter the party's basic image and identity.

This is telling. The mission of conservatives 30 years ago was to claim the Republican Party as their own -- and they succeeded. But today they're on a mission to eliminate even the occasional dissent from that party. They may succeed again -- but at a severe long-term cost to the GOP.

Shares