Questions about whether racism is part of what's behind the Tea Party movement won't go away. To many liberals, of every race, it seems no accident that the movement emerged shortly after the election of Barack Obama, our first black president. While Tea Party supporters insist they're protesting big government, it's hard not to notice they were silent as George W. Bush exploded the budget deficit and initiated the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), commonly known as the bank "bailout."

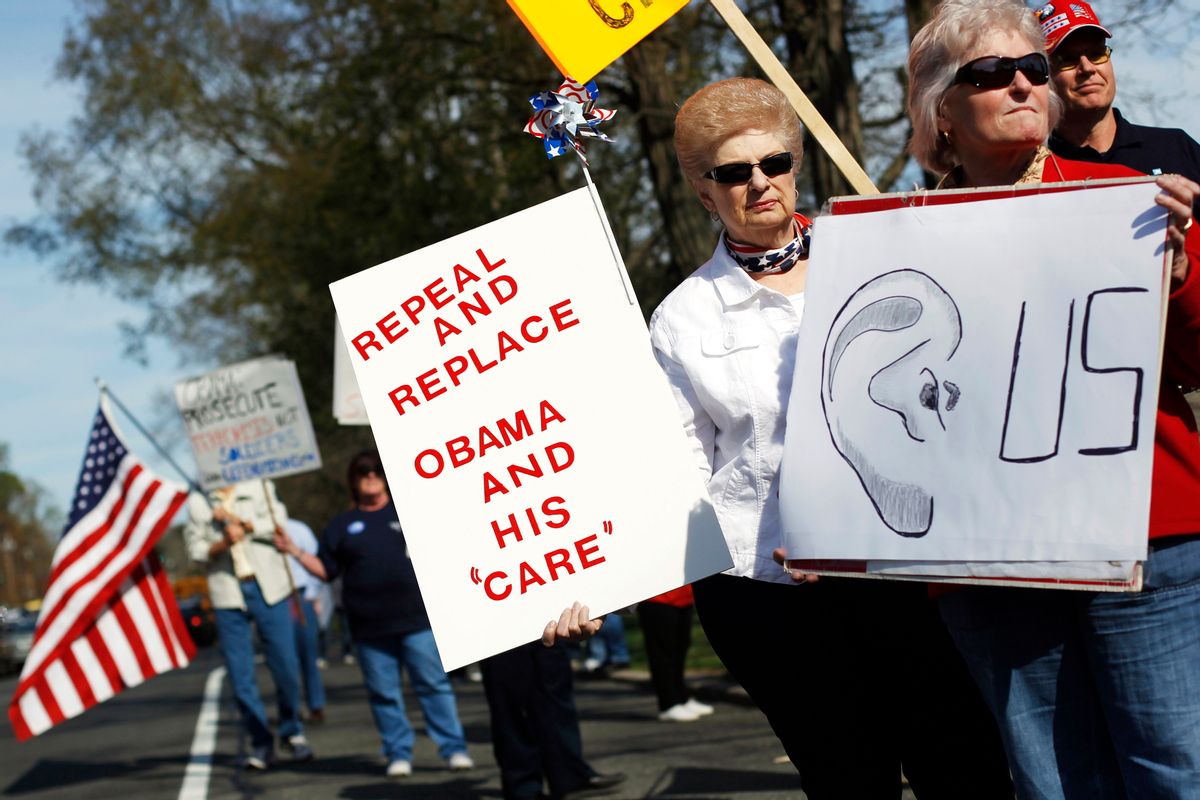

Then there are the signs and slogans that depict Obama as Hitler, as a non-human primate, or as a "witch doctor" complete with a bone through his nose. Reports that some Tea Partiers spit on a black legislator as others hurled the most painful racial epithets, as the healthcare reform bill passed, only intensified the debate over Tea Party racism.

Into that volatile climate, my University of Washington team released results, based on a larger study on race and politics in seven states, six of which were battleground states in 2008. We asked a lot of questions about race and racial attitudes, but we also asked people to tell us whether they support the Tea Party. Our initial analysis revealed that among whites, strong supporters of the Tea Party were less likely to see black people as hardworking, intelligent and trustworthy than whites who were strong skeptics of the Tea Party movement. Our findings were publicized widely, including here on Salon. And immediately, requests for our data poured in. We were happy to oblige.

Real Clear Politics columnist Cathy Young took her own look at our data, and reached different conclusions. In her piece, "Tea Partiers Racist? Not So Fast," she makes at least two claims, based largely on our study. Beyond the ad hominem charges she makes against us, among them that my team and I harbor "standard left-of-center view(s)," she claims that Tea Partiers aren’t that different from white non-Tea Party supporters in how they see blacks. And where she does acknowledge differences in racial attitudes, and more "racial resentment" among Tea Party supporters, she claims they reflect the fact that Tea Partiers are simply more conservative than others whites, supporting a bootstrap approach to reducing poverty and a limited role for the national government.

Where initial reports on our study only compared the racial attitudes of strong Tea Party supporters with white Tea Party skeptics, and found the Tea Partiers more likely to have negative views of blacks, the broader data set actually allows comparisons of Tea Partiers' attitudes with the attitudes of all whites, including those without strong views of the Tea Parties as well as those who said they'd never heard of the movement. Young is correct that our study found that whites overall, not just Tea Party supporters, harbored some negative stereotypes about blacks. Indeed, although more white Tea Party skeptics considered black people trustworthy than did white Tea Party supporters (57 percent to 41 percent, respectively), those white Tea Party skeptics also found whites more trustworthy than blacks (72 percent of them saw whites as trustworthy). The white Tea Partiers were only a little more likely to think blacks are less intelligent than whites than white Tea Party skeptics.

Young admits there were much bigger gaps on questions about whether blacks are sufficiently hardworking, rely too much on government help and on other indicators of "racial resentment." See the table below, with more detail on our site.

But there Young merely saw conservatism: the belief that those who work hard will be rewarded, and small government is best.

I draw different conclusions from the data than Young did. First of all, the fact that even non-Tea Party supporting whites in our study harbored some questionable racial attitudes wasn't particularly surprising. Racial prejudices endure. It is worth noting, moreover, that the white voters in the six battleground states are more conservative in their political views than whites nationally. Even when we include the relatively liberal California, 57 percent of whites in the sample claim to be conservative, in contrast to the 45 percent of whites who identified as conservative nationally in the 2008 American National Election Study.

Furthermore, only 20 percent of our sample claim to be liberals, compared to 28 percent nationally. In sum, because so many in our sample were conservative (and so few liberal), and a higher share were Tea Party supporters than in other polls, it's possible that the "average" of racial attitudes among whites is different from what it would be in a nationwide sample.

Young's second point, that Tea Partiers view blacks as less hardworking, and hold more "racial resentment," because of conservatism, not racism, is an interesting one. It is certainly true that the perception that blacks lack a strong work ethic, and look for "special favors” from the government, is consistent with conservative values and conservative politics; not an unreasonable assertion. But to stop here, and reduce racial resentment to conservatism, is at best premature; at worst, it’s irresponsible. In at least three other articles on this topic, I’m on the record saying that one shouldn’t conflate the apparent racism in the Tea Party movement with conservatism.

Apparently, Young doesn’t appreciate the capacity of social scientists to take the analysis further. If she did, I doubt she would’ve claimed that support for the Tea Party was simply a proxy for conservatism. Suppose that most Tea Party supporters are what some call "principled conservatives." That is, they’re simply about a small federal government, fiscal discipline and free markets. In fact, our data show that when you account for/control for conservatism, and partisanship to boot, there’s still a strong statistical connection between support for the Tea Party -- rather than conservative politics generally -- and racial resentment. Indeed, ideology does matter: If one is conservative, he or she is 23 percent more likely than a liberal to hold racially resentful attitudes. Even so, we found that Tea Party supporters are even more likely than conservatives who don’t support the movement to believe that blacks simply need to work harder, and that the legacy of slavery and discrimination has no effect on blacks’ current condition in America society.

It should also be noted that the support for small government and "states' rights" expressed by Tea Partiers have rarely been entirely free of racism, or racial motivation. Dating back to before the Civil War, the South leaned hard on the doctrine of states' rights as a means of preserving slavery. During the 20th century, claims about states’ rights animated the Dixiecrats, who had fallen out with Truman’s Democratic Party as it installed a more racially liberal party platform. Indeed, research conducted almost 30 years ago, by David Sears and Jack Citrin, suggests that support for small government and tax revolts are motivated by some whites' desire not to have their taxes redistributed to help blacks and other minorities.

Young links another finding in our study -- that the Tea Partiers support government restrictions on civil liberties -- to mere conservatism. But, again, supporters of the Tea Party movement are more likely than other conservatives to support such measures -- even though the movement's supposed goal is freedom from government tyranny. Indeed, controlling for conservatism, Tea Party supporters are 28 percent more likely to say that it’s OK for the government to detain suspects indefinitely without filing charges.

And Young also makes one mistake with information that came from a CBS News/New York Times poll of Tea Partiers: She claims that the proportion who make more than $250,000 annually, 12 percent, is essentially the same as in the general population, where she says 11 percent make more than $250,000 annually. In fact, less than 2 percent of Americans make more than a quarter of a million dollars a year.

Young is honest enough to admit at the end of her piece that there is a "darker side" to the Tea Party movement: "too often, they promote the politics of personal attack and demonization, of hyperbole and hysteria." But she goes on to say "they are no more guilty of this than were Bush-era protesters on the left." Our study didn't explore the attitudes of Bush-era protesters on the left. We did, however, compare the racial attitudes of white Tea Party supporters to those of whites who don't support that movement, and on virtually every measure, the Tea Partiers harbored more negative views of blacks, even as we accounted for conservatism and partisanship. This suggests that the Tea Party movement is about more than ideological differences, or the party with which one chooses to identify. Perhaps the difference is the cry of "states' rights" thats a pillar of the movement. If so, we need to keep an eye on them.

Christopher Parker is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Washington. He is the author of "Fighting for Democracy: Black Veterans and the Struggle Against White Supremacy in the Postwar South."

Shares