British journalists love nothing more than a big, fast-moving story, so we're understandably excited about the fallout from the News of the World phone-hacking scandal. Just today, Andy Coulson, the paper’s ex-editor, was arrested, while Clive Goodman, the paper’s former royal correspondent, was rearrested. There’s talk of reams of emails being deleted at News International’s Wapping headquarters, and Rebekah Brooks, the company’s chief executive, is hanging on by her fingertips. It’s thrilling. This is what we live for.

Yet many of us are waking up to the fact that it could result in some of our cherished freedoms being curtailed. There’s no First Amendment in Britain, no constitutional guarantee of press freedom. The prime minister, David Cameron, gave a press conference this morning, in which he tried to put some distance between himself and the Murdoch empire. (Andy Coulson used to be his communications director, and he was a guest at Rebekah Brooks’ wedding.) He announced that there would be two official inquiries – one into the phone-hacking allegations and why the initial police investigation uncovered so little evidence of wrongdoing, and one into the ethics of the press. He also said the press could no longer be relied upon to regulate itself, and his government would create a new independent regulator. “It is vital that a free press can tell truth to power,” he said. “It is equally vital that those in power can tell truth to the press.”

As a colleague of mine pointed out in the Daily Telegraph, that phrase had an ominous, Orwellian ring to it. Does Cameron mean that, in future, her majesty’s government will be able to dictate to the press what truths it can and can’t tell? Almost everyone in the media accepts that some sort of privacy law in Britain is now inevitable. Our newspapers are already bound by the privacy clauses of the European Human Rights Act, but many European countries have additional privacy laws that make it much more difficult for their papers to expose the corrupt practices of senior politicians and officials. France is a particularly egregious example. I have to be careful what I say about Dominique Strauss-Kahn because he could take advantage of Britain’s draconian libel laws to bring a multimillion-pound lawsuit against me. (In the U.S., the burden of proof is on the plaintiff to demonstrate that what’s been written about him is false, whereas in the U.K. the burden of proof is on the defendant to demonstrate that what he’s written is true.) But a British equivalent of DSK would not have been able to escape the scrutiny of the British tabloids.

The creation of an “independent” regulator and the introduction of tough new privacy laws are both things the British political class has wanted to do for years, and our fear is that Cameron will take advantage of the public’s revulsion at the News of the World phone-hacking revelations to clip our wings. That could mean the end of our rambunctious, adversarial media culture.

I’m one of the few British journalists who have been prepared to speak up for Rupert Murdoch and the News of the World since the scandal broke. I wrote a defense of tabloid journalism in this week’s Spectator, and I appeared on the BBC yesterday to defend Murdoch against the London editor of Vanity Fair. I’ve had a busy day today, shuttling between television and radio studios, doing my best to put the case for the ink-stained wretches of News International.

Defending Murdoch’s record in the U.K. isn’t that hard. He broke the back of the antediluvian print unions, revolutionized broadcasting and has kept the London Times afloat even though it loses tens of millions of pounds a year. He’s often accused of interfering in his papers, ordering the editors to support whichever political party has promised to do the most to further his business interests. But most editors who’ve worked for him describe him as a model boss. He’s loyal and doesn’t skimp on budgets, the two most important qualities in a newspaper proprietor.

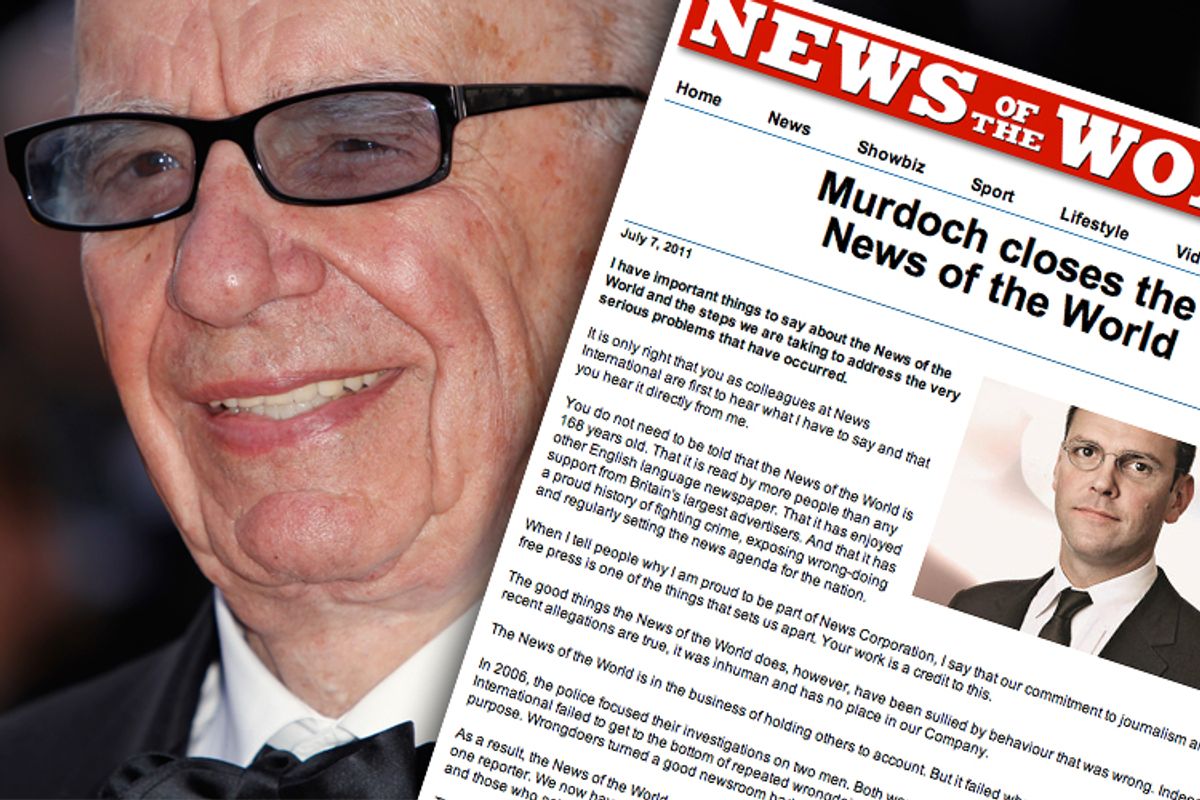

Making the case for the News of the World, which News International has announced it’s shutting down, is more difficult. The paper’s staff have engaged in some unforgivable behavior over the years, but they’ve also been responsible for breaking some fantastic stories. The Screws, as it was called, didn’t hesitate to speak truth to power when it had the goods on somebody. One of the paper’s biggest scalps was that of Jeffrey Archer, then the vice-chairman of the Conservative Party, who ended up going to jail following the paper’s revelations that he had paid off a prostitute. More recently, it exposed members of the Pakistani cricket team for throwing matches in return for cash bribes. One of its most colorful members of staff was Mazher Mahmood, known as the “fake sheik” thanks to the fact that he disguised himself as a rich Arab in order to dupe celebrities into trying to sell him cocaine or arrange access to their powerful friends in return for cash. He counted Sarah Ferguson among his victims.

There was something almost engaging about the paper’s lack of respectability. Lots of commentators have pointed to its double standards – the cavernous gulf between the moral sentiments of the leader columns and the behavior of the journalists – but, in itself, that hypocrisy had a kind of pantomime appeal. The News of the World was part of the scenery in the music hall farce that is British public life. It’s been going for 168 years and featured in the opening section of George Orwell’s famous essay on the decline of the English murder. The paper’s reptilian hacks were the rude mechanicals of Fleet Street – stock characters in a company of players that will be diminished by their departure, even if they were unloved when they were around and occasionally behaved appallingly. I will miss the fake sheik.

Clearly, there are people who should be protected from tabloid intrusion, such as the victims of the 7/7 bombings or the families of dead soldiers (just some of the people who are alleged to have had their phones hacked by the News of the World). But how do you shield them without also shielding wrongdoers? A privacy law and an “independent” regulator wouldn’t just protect the innocent, it would also protect the guilty. Without papers like the News of the World – without Rupert Murdoch – Britain would be more like France.

I don’t want to sound too alarmist. British politicians have promised to rein in the tabloid press before, most notably after the death of Princess Di, only for everything to carry on as normal after a couple of months. But this feels like a watershed moment, a turning point in the relationship between Westminster and the Fourth Estate. If we’re not careful, the excesses of some News of the World reporters may mean that the freedoms we’ve enjoyed for centuries are about to be withdrawn.

Shares