The world's most common sexually transmitted infection has just gotten a little bit scarier, as an international group of scientists announced yesterday that they have identified a new, drug-resistant strain of gonorrhea in Japan. Experts warn that the development represents a "possible precursor to a global health scare."

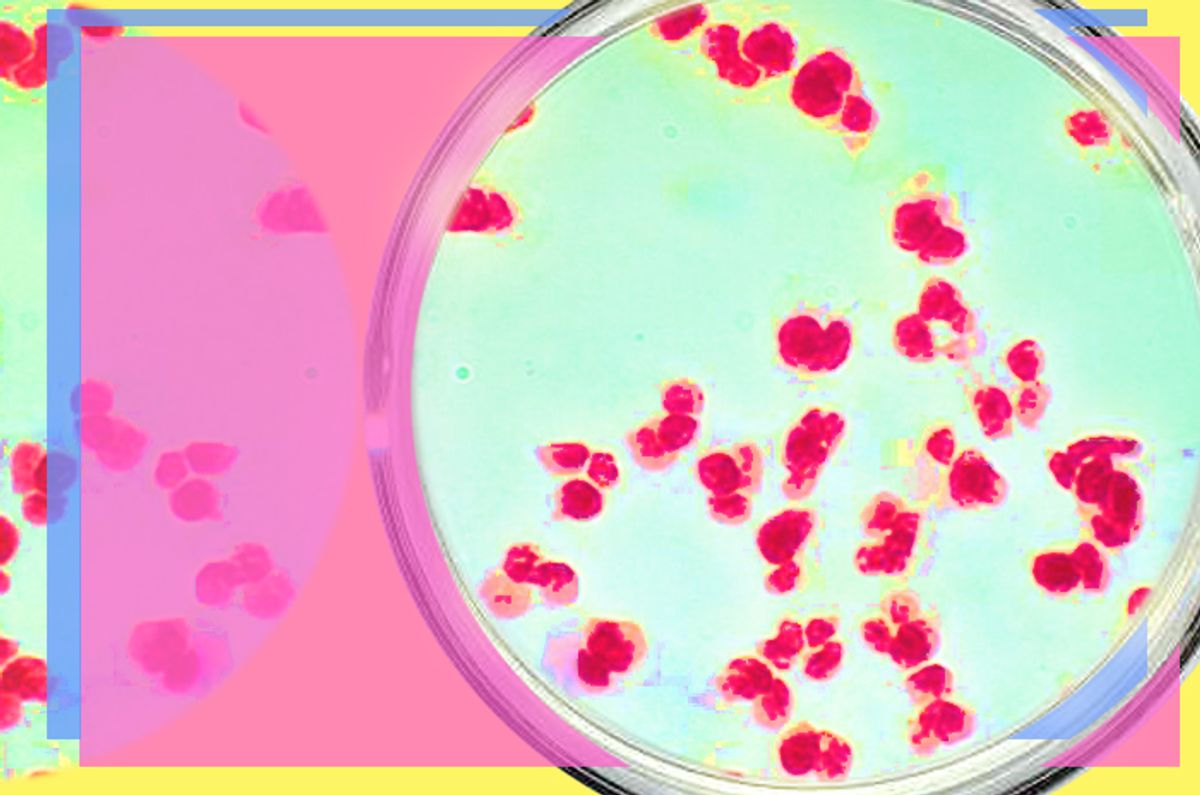

Colloquially known as "the clap," gonorrhea is a bacterial infection that afflicts some 700,000 Americans annually. The bug can lead to all sorts of painful and damaging symptoms in a host's nether regions, sometimes leading to infertility in both men and women. It can also increase the chances of HIV transmission, kidney failure, meningitis and a host of other complications. In extreme cases, it can lead to death. Cephalospirins, a class of antibiotics, have been the standard (not to mention the only effective) treatment for the disease since the 1940s. But genetic mutations in one strain of the bacteria, called H041, have rendered the treatment ineffective in some patients.

While there are no reported cases yet of the new superbug in the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention did announce last week that it was noticing greater resistance in the bacteria to cephalospirins in some Pacific states, like Hawaii and California. Gail Bolan, director of STD prevention at the CDC, confirmed fears of a gonorrhea super-strain, but said that the agency is hopeful that there's still time to find a solution:

We do fear that based on what we are hearing around the world, we will see cephalosporin-resistant gonorrhea. We don't know when this is going to happen, but the hope is that we have a few years to identify other treatments.

This isn't the first time that scientists have had to grapple with new types of gonorrhea evolving resistance to predominant treatments. Penicillin and sulfa drugs were originally used to fight the disease after its discovery, but proved ineffective before long. Likewise, an Ontario research team in 2009 found that a strain of the bug had rapidly evolved immunity to another set of antibiotics called quinolones, between 2001 and 2006. Dr. Magnus Unemo, who helped pinpoint the h041 strain in Japan, acknowledged that its emergence was startling, but not all that surprising:

Since antibiotics became the standard treatment for gonorrhea in the 1940s, this bacterium has shown a remarkable capacity to develop resistance mechanisms to all drugs introduced to control it. While it is still too early to assess if this new strain has become widespread, the history of newly emergent resistance in the bacterium suggests that it may spread rapidly unless new drugs and effective treatment programs are developed.

The good news is that researchers have been able to devise new ways to combat the disease in the past. The bad news is that with budgets being slashed across the board, there are some concerns about whether pharmaceutical companies will pursue alternative treatments, or merely continue to produce drugs that have worked in the past.

Shares