Ken Berger can't move his car. Although his sleek new silver 2001 Corvette can rev from zero to 60 in under five seconds, right now he's wedged in between dozens of vehicles on the freeway and can go nowhere. It's 4:30 p.m. in Oakland, Calif., on a November afternoon, and Berger is getting antsy that he'll miss his 5 o'clock meeting.

So what's a Silicon Valley consultant to the wireless industry to do?

Just this: He reaches into his bag, fires up his new Sony laptop, connects it to his Ricochet wireless modem, logs onto www.mapquest.com and locates an alternative route using side streets. And he makes his meeting. Barely.

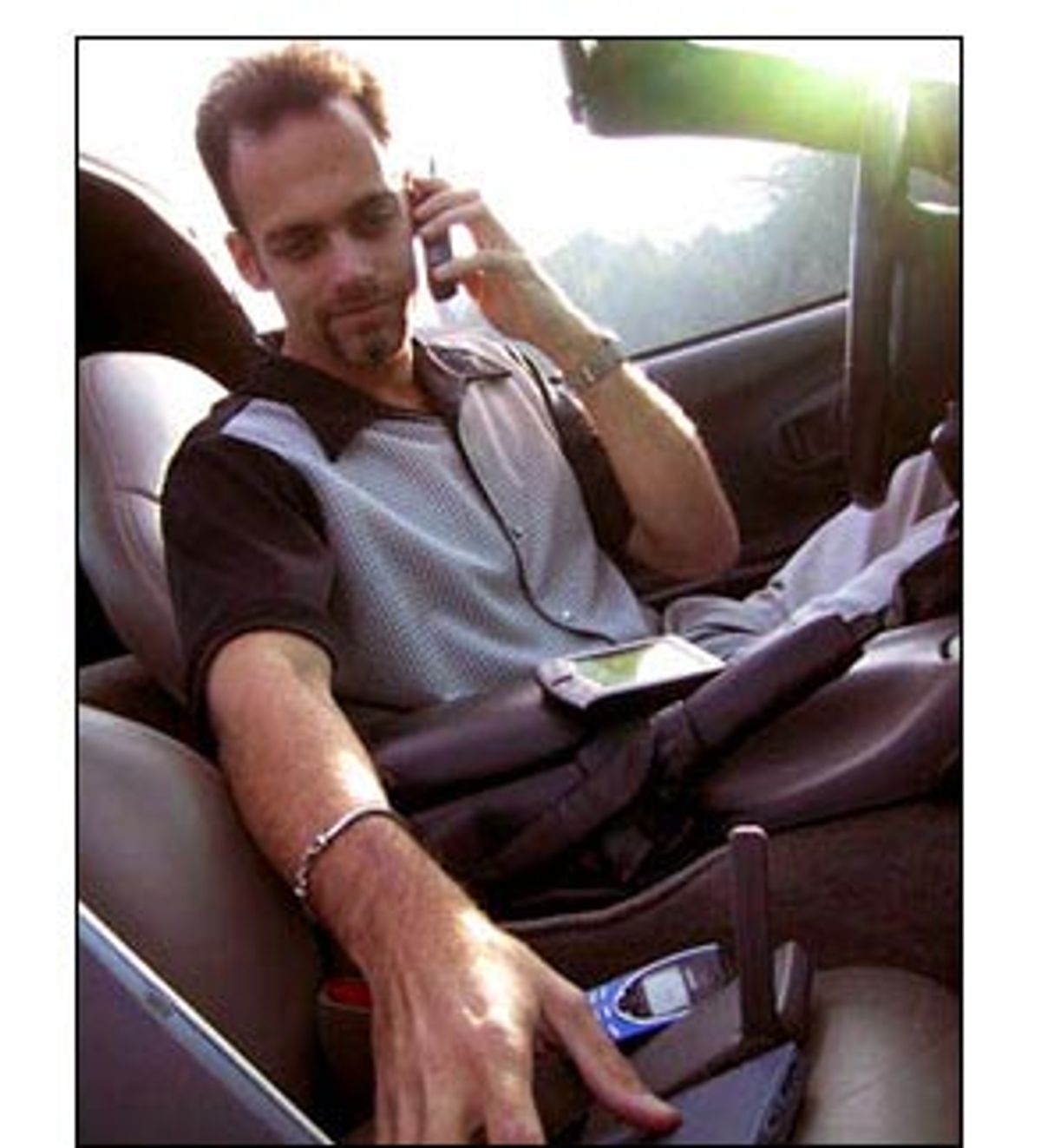

For the 33-year-old entrepreneur, who spends hours each week traveling between his home office in San Francisco and meetings throughout the Bay Area, his car has become a second workplace. And when in the driver's seat, he brings with him all of the accoutrements of the modern high-tech command center -- a Palm Pilot, wireless modem, computer and, of course, his gleaming new cellphone, the Nokia 8290.

"It used to be so frustrating when you were stuck in traffic because you were throwing time away," says Berger, who schedules conference calls for times when he knows he'll be on the road. "Now, even though traffic has gotten worse, you can reclaim part of that time by being productive."

While Berger may seem as wired as a Christmas tree strung with too many blinking lights, his use of new technology on the road is not all that unusual these days. And though he insists he has never had a close call while fiddling with his devices or networking on his cellphone, it is exactly that possibility that worries legislators, safety experts and others -- and has spurred 10 towns and counties, including two within just the past few weeks, to pass ordinances restricting wireless phone use while driving.

The issue has gained new visibility because of this week's trial of Jason Jones, the nation's first cellphone-using driver known to have been charged with vehicular manslaughter. The non-jury trial, held in Upper Marlboro, Md., ended Wednesday evening with Jones' acquittal on the manslaughter charge. The judge, however, found him guilty of negligent driving and gave him the maximum sentence possible: a $500 fine and four points on his driver's license.

According to a recent study by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 85 percent of the estimated 107 million cellphone subscribers in the United States use them while on the road. And many of these devices are good for much more than social chitchat or business dealmaking; they let you receive and send e-mail, access information on plummeting (or, more rarely these days, rising) stock prices, find out who's ahead in the post-election presidential race at a given moment and browse through your favorite Web sites -- all while cruising the highways at 80 miles per hour. (Also coming to the U.S. cellphone market soon: instant messaging.)

But what may be even more worrisome is the shipment just delivered to a car dealer near you: autos equipped with up-to-the-minute features like hands-free cellphones and monitors the size of mini-T.V. screens, which can display not only the driver's geographic location but weather, sports and news items as well. Hey, why not read about Robert Downey Jr.'s most recent arrest as you round that blind curve?

Those in the traffic-safety business term these in-car activities "driver distraction." And this catchall phrase can be applied not just to activities associated with new technology but to almost everything we do in our cars, from inhaling a fast-food burger to applying your favorite Mac Verve lipstick to lunging at the radio to flip off that irritating Backstreet Boys single.

Law enforcement and highway patrol authorities are especially concerned about driver distraction, which is believed to account for roughly a quarter of all crashes and is considered largely preventable. And they express growing concern that the proliferation of electronic devices is leading to so much techno-multitasking in cars that it is endangering hundreds of thousands of people's lives each year.

There are no reliable statistics for how many car accidents are linked to cellphone gabbing. But according to a 1997 study in the New England Journal of Medicine, drivers using the devices are four times more likely to suffer a crash -- about the same increased risk as getting behind the wheel after downing one too many martinis.

Moreover, according to Tom Dingus, director of the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute, it is estimated that between 600 and 1,000 people a year die in cellphone related crashes. In the future, he says, that figure is expected to hit 2,000 as more people subscribe and then take to the road.

"We're bringing more and more toys into our vehicles," says Frances Bents, a co-author of the NHTSA cellphone report and a vice president of Dynamic Science Inc., a consulting company that conducts health and safety research. "There are a lot of people who are going to die before we fully understand what kind of problem we've created."

So far only six states -- Minnesota, Oklahoma, Montana, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Tennessee -- have implemented a policy of tracking whether cellphones are implicated in crashes. And even officials involved in collecting the data acknowledge that it's extremely difficult to determine how often a phone is to blame and that the actual incidence is far greater than reported.

In Minnesota, for example, cellphones and CB radios were identified as being responsible for just 0.3 percent of the more than 2,500 single vehicles accidents for 30- to 34-year-olds in 1999. But Minnesota Department of Public Safety spokeswoman Cathy Clark says that the data does not reflect the realities of the road.

"The reason is that most drivers who are talking on their cellphones and are involved in a crash are not going to admit to law enforcement when they're doing it," she says. And unless there is a witness who saw the driver using a cellphone, adds Clark, it most likely gets coded under "inattentive driving" -- the No. 1 recorded cause of accidents in Minnesota.

To promote the idea of passing legislation to restrict the practice, politicians and traffic safety advocates have paraded the stories of the wounded and the dead before the public to show what happens when you mix cellphones and driving -- what many now consider a deadly cocktail. Celebrity-hungry media outlets, of course, have been eager to comply.

These "poster children" for the crusade include 2-year-old Morgan Lee Pena, killed last year by a cellphone-using driver; Ron Silber, who can no longer walk unaided; and John Michael and Carole Hall, who one day last year pulled over to the shoulder of the road to let their 10-year-old go to the bathroom. While they were sitting in their Mazda waiting for him, Jason Jones, a 20-year-old Naval Academy student returning home from his girlfriend's house, slammed into the car, killing them.

Jones was on his cellphone while traveling at a high rate of speed, according to prosecutors who pressed a manslaughter charge. Photos taken at the scene of the accident show his car with the cellphone plugged into the cigarette lighter even after the accident, said Michael Herman, assistant state attorney for Prince George's County, Md. Jones' attorney did not return a phone call seeking comment.

"The defendant admitted that he was dialing on the cellphone and all of a sudden he looked up and 'boom,'" says Herman. "We believe strongly that the Hall family were innocent victims of a very avoidable collision that was caused by the gross negligence of the defendant, and that meets the legal criteria of manslaughter."

Jones pleaded not guilty to the manslaughter charge, which could have netted him 20 years in prison. Even though Jones wasn't convicted on the manslaughter charge, sources close to the case say that the state attorney used the case to to nudge Maryland legislators to pass a law restricting the practice.

The Halls were from East Northport, N.Y., a town in Long Island's Suffolk County; they were passing through Maryland on their way back from a Thanksgiving celebration in Virginia. Their death so rocked Suffolk, a region with 1.4 million residents and the home of the Hamptons, that officials there passed legislation in October banning the use of handheld cellphones in a moving car. Hands-free devices will still be permitted. This is anything -- from an ear piece to a speaker-phone adapter -- that allows you to use the cellphone without holding it in your hand.

"Hopefully, it will heal the wound," says Jon Cooper, the legislator who wrote the bill. "Another aspect of the law is that Suffolk County is sending a message to cellphone manufacturers and carmakers about all these other gadgets that they're sending our way. The message is this: Go ahead and improve our lives, but consider the implications of your products on highway safety."

The Halls were not Suffolk County's first victims of cellphone-using drivers. Years before them was Ron Silber, a man who had always thought about cars and safety in his capacity as supervisor of the traffic safety division of Babylon, another Suffolk town.

On a bright October day in 1993, he got into his Toyota station wagon with his wife, daughter and prospective son-in-law to drive to a pumpkin patch near their home. As the car approached the patch -- the large, round pumpkins were already within view, recalls Silber -- a Ford Explorer drifted into the same lane and crashed into them head-on. Ironically, the woman driving it had taken her cellphone with her for the first time, he says.

The next thing Silber remembers is waking up in the nearby emergency room. His life hasn't been the same since. One hip was so badly mangled that he lost it after several operations. He still requires a walker to get around.

"I've been living with pain for so long -- unstoppable, unforgiving pain -- that I've gotten used to it," says Silber, 63. "My mind now diminishes it, but my body can't, of course, because I have no choice but to live with it."

The Suffolk law goes into effect on Jan. 1. Officials plan to inform residents and motorists through publicity efforts and signs on the freeways and at other entry points to the county. The fine for each offense: $150.

In fact, when it comes to cellphone laws, the U.S. lags behind many other industrialized nations. At least 20 countries -- including Spain, Japan, Israel and Singapore -- have passed some type of legislation restricting the devices' use while driving. Here, 37 states have considered legislation over the past five years; all of the bills have died.

Nine years ago, in Massachusetts State Rep. Salvatore DiMasi's district of Boston, a cellphone-using driver ran a woman driving her kids to school off the road. In response, DiMasi proposed a bill that he says couldn't garner enough support to overcome opposition from the cellphone lobby and companies relying on traveling salesmen.

But DiMasi believes that the political climate is changing now, and he plans to reintroduce his bill this month. "Ten years later, more people use cellphones and I don't know anyone who hasn't been cut off by someone talking or dialing on a cellphone," he says.

In its current formulation, DiMasi's bill would effectively ban the use of all cellphones, but he says he's ready to compromise for political expediency and allow hands-free cellphones. Some safety experts maintain that hands-free models are not necessarily safer; they say that the devices distract drivers not because they need to be held, but because of the concentration they demand during conversations. But since handheld models account for a majority of the overall market, DiMasi and others believe that even compromise legislation will still make a big dent in the numbers of people actually dialing and driving.

With states having such difficulties passing bills, local officials say they are no longer willing to wait. "I think what has happened is cellphones have become so pervasively used in such a short time, now it's become acceptable," says Jim Reed, transportation program director of the National Conference of State Legislatures, which researches issues of interest to elected officials. "But it's just like the old expression of trying to close the barn door after the horse has gone."

Suffolk is one of 10 locales -- the others are West Conshohocken, Conshohocken, Hilltop Township and Lebanon, all in Pennsylvania; Carteret and Marlboro, both in New Jersey; Brooklyn, Ohio; Rockland County, N.Y.; and Brookline, Mass. -- that have passed bills banning the use of handheld cellphones while driving. Rockland County just passed its bill this week. Brookline, an affluent suburb of Boston, actually forged into new territory when it passed its bill several weeks ago and banned not only handheld cellphones but "similar handheld devices" -- a formulation that could include Palm Pilots and similar items.

The ordinance has sparked a fair amount of anger. Lisa Liss, a Brookline town meeting representative and the author of the ordinance, has received several hate messages; one person accused her of being "a pinhead and a Democrat." Liss laughs about that message now, but she recognizes the emotions that can be roused when the government seeks to legislate what people can or can't do in their cars.

Liss, a 60-year-old retired librarian, does not consider herself a technophobe. And she doesn't hate cellphones; she even has one in her car to use in case of emergency, which is permitted under the ordinance.

However, she decided to write the bill after a car swerved into her lane one night, almost causing a collision. "I repeated this story to several of my friends and almost all of them had either read about a near-accident or tragedy or experienced the same thing," says Liss. "And that brought it into my consciousness -- if this is happening just among my small friends and acquaintances, it must be multiplied across the country."

The ordinance has not yet gone into effect. The state's attorney general is reviewing it to determine if it conflicts with a state law (passed two decades ago) allowing motorists to use a cellphone while driving as long as they have at least one hand on the wheel.

Surrounded on three sides by Boston, Brookline is a quaint, tree-lined community through which almost as many people drive each day as actually live there. Many commuters even pass through it on their way to Boston without taking note that it is a distinct municipality. That would make it difficult, say some, to actually enforce a traffic law that diverged from Boston's regulations.

Brookline police chief Kevin O'Leary is one of those worried about enforcement. While he supports the concept behind the ordinance, he is concerned that the term "handheld device" is vague enough to mean just about anything, such as the handheld radios many taxi drivers use. Sitting in his office on a recent afternoon, he suddenly rises and strides over to the window to illustrate what he means. "You see that?" he says, pointing to a nearby building. "That's Boston, less than 500 yards away."

O'Leary worries that people won't know when they are entering Brookline and so won't be aware that they are breaking the law. As a result, he says, he fears that his officers might face a backlash from angry and aggressive motorists who have no idea that they are cruising through a handheld device-free zone. He also believes that existing reckless driving laws may be sufficient to address the problem.

"Not everybody is a bad driver," explains O'Leary. "There are people who are generally conscious of what they are doing and don't drive crazy just because they are using a cellphone. And this law says everybody is a hazard. And I don't think that's true."

While O'Leary says he believes that it would be more effective to enact legislation at the state level, police officer Rich Hovan of Brooklyn, Ohio, a Cleveland suburb, says enforcement of the town's local ordinance has not been a problem. Since March of last year, when Brooklyn became the first place in the United States to pass such a law, more than 275 tickets have been issued.

Hovan has become a minor celebrity of the anti-cellphone brigade -- he even appeared once on "Oprah" -- and has issued most of Brooklyn's tickets himself. It was on "Oprah," in fact, that he met the Penas of Hilltown Township, Pa., who were appearing on the show to discuss the cellphone-related death of their toddler, Morgan.

"I write every single one of those tickets in Morgan Pena's name," says Hovan. "I sign her initials, M.P., where my name goes. I told her family that her name won't be forgotten."

Representatives of the wireless industry say that without data on the number of crashes caused by cellphones, it is unfair to sanction their use and that of other electronic devices.

"Wireless phone use is just one of many driver distractions," says Dee Yankoskie, manager of wireless education programs at the Cellular Telecommunications and Internet Association, an industry trade group. "We don't want wireless phones to be singled out when people do everything from eating a cheeseburger to cleaning up coffee in their cars -- especially since a wireless phone is the only potential distraction that can save your life or the lives of others."

Indeed, in July the Harvard Center for Risk Analysis issued a study (funded by AT&T Wireless) that delineated some benefits of using a cellphone in the car. According to the study, cellphones can serve many purposes, from reporting crimes to making emergency calls; in fact, 1 million emergency calls to Massachusetts State Police were made from wireless phones in 1998.

Joshua Cohen, a senior research associate at the center and a co-author of the report, says that drivers would be less likely to have their phones with them for emergency purposes if the law bans their use under normal circumstances. As a result, the report concluded that it was premature to pass such ordinances.

"There are laws that you can't drive recklessly," says Cohen. "There is no law to control you when you play around with your CD player. There's a responsibility when you drive. That means you don't fool around with your radio when it's going to increase your risk of getting in an accident. To try to come up with a separate law for each of these devices is probably counterproductive."

While telecommunications giant Verizon Wireless recently announced its support for statewide laws restricting handheld phones in cars, it remains vehemently opposed to local legislation. "Is every community going to start erecting signs at every entry point detailing what their local ordinances are?" demands Verizon spokesman Jeffrey Nelson. "Common sense says that is more confusing for people on the road than less confusing."

As Nelson speaks, a symphony of street noise, including blaring horns and scooters chugging by, peppers his words. He is speaking on his cellphone and defending Verizon's stance from -- where else? -- his car.

Deciding whether to push for local or state legislation might prove to be the least of critics' worries. Car manufacturers are shipping new models with built-in phones as well as the Global Positioning System, a navigational device allowing a driver to view a screen pinpointing a car's location.

"All of these devices are certainly not essential to the driving experience, and research isn't being done ahead of time to assess the risk they present not only to the driver but to others," says Bents, the co-author of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration report. "And of course there's no crash data available, and you have to wait until someone hits someone."

What's more, in all but two classes of Mercedes-Benz 2001 product line, owners can opt for a 3-inch-by-4-inch monitor -- lodged in the spot where the radio normally is -- that displays individually selected news or sports or weather reports from CNN Interactive while they're in the driver's seat. The service costs just $125 a year.

Mercedes-Benz U.S.A. spokesman Jim Resnick insists that the manufacturer takes driver distraction very seriously. He points out that the built-in cellphones are hands-free models; the news items are no more than 25 words long and only appear after the driver actively overrides an electronic suggestion that the text be delivered later.

But that begs the question: Does the driver have any business reading while at the wheel? "We wouldn't offer it if we didn't believe it was safe," says Resnick. "The text is no more difficult to read than climate control or the radio or any number of other features in the center dashboard."

That may or may not be true; Resnick has no data yet to back up his claims because the first cars sporting the feature only came out in July. Yet Resnick's attitude is just the sort of approach to the issue that enrages Silber.

Silber has learned to forgive the woman who robbed him of his ability to walk on his own; he recognizes that she simply made a terrible mistake. Instead of blaming her, he saves his scorn for those who manufacture these new gizmos without sufficient regard for safety concerns. He recounts his reaction at one of the Suffolk County executive meetings at which the cellphone bill was discussed.

"There were a couple of lawyers from the phone industry companies reading their briefs, and it came my turn to speak and I looked at them directly," he recalls. "I said, 'What the hell are you waiting for? The bodies are piling up. Do you want the pile to be higher?'"

Shares