As you drive south from Washington on Interstate 95, the high-tech corridors of northern Virginia give way to green grass and rolling hills and something that begins to look like the South. Pickups start to outnumber Volvos and VWs, and Starbucks gives way to the "scattered & smothered" comfort of Waffle House.

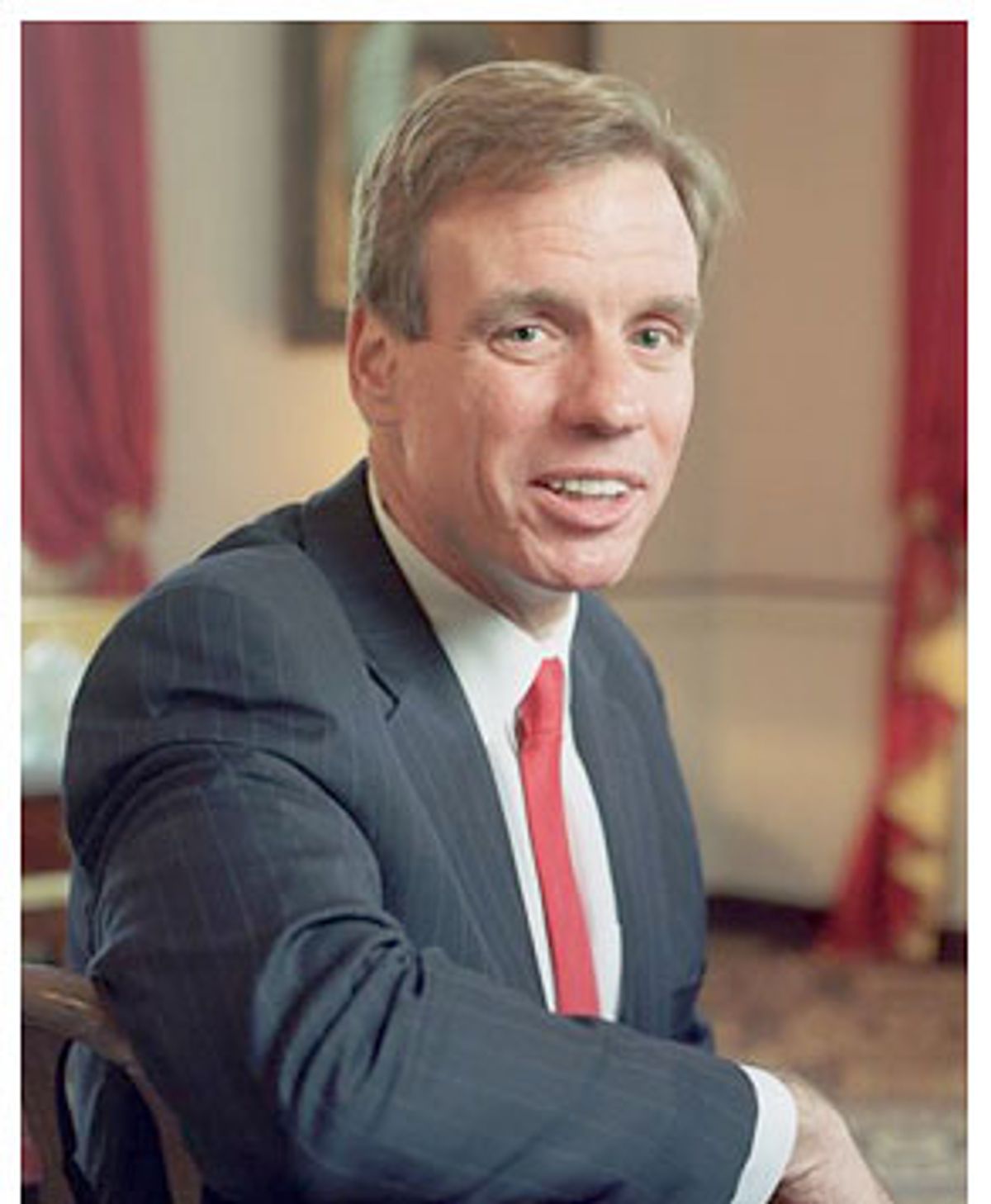

It's a long way from Washington to Richmond -- and even farther to the rural counties of southern Virginia -- but Mark Warner has covered the ground. The Democrat, a 50-year-old multimillionaire venture capitalist from Indiana by way of Connecticut, got himself elected governor of Virginia in 2001 in large part by reaching out to rural voters who were supposed to be in the Republicans' pocket. Warner sponsored a NASCAR team, used a bluegrass song as his campaign theme, and appealed directly to gun-loving hunters and sportsmen -- and it worked. John Kerry, he is not.

"People in rural America may speak a little slower, but they can spot a phony a mile away," Warner says. "You see other candidates who say, 'Let's just do the optics.' But unless you feel as comfortable hanging out at a country fair or having a beer and eatin' some barbecue as you do at your high-end, high-tech reception, people are going to see through that."

Winning elections is about more than beer and barbecue, of course: Warner says that Democrats have to engage voters in a conversation about the future, particularly the future of rural areas, small towns and midsize cities where the global economy hasn't delivered on its promise. Most of all, he says, Democrats have to give voters hope.

Can Warner give Democrats hope? In a column earlier this month, Newsweek's Howard Fineman ticked off Warner's selling points: He's a governor, not a Washington politician; he's got money and the ability to raise more; he's got a base of supporters in the high-tech world; he's a Southerner, or at least he is one now; he's got crossover appeal because of his centrist views; and he's got time because Virginia terms out its governors after just four years.

Warner is establishing a federal political action committee and has hired a former Al Gore aide to advise him on national politics. He could use the PAC for a run at the U.S. Senate or for a presidential campaign in 2008, but Warner is coy when it comes to his future plans. "You know," he says, "I want to be part of this debate."

Warner sat down with Salon recently for an hour-long interview inside Virginia's 192-year-old governor's mansion.

There's been a lot of talk about the Democrats' need to "rebrand" themselves as a political party. Do you buy into it?

If the Democratic Party continues to think that the way back to national prominence is to somehow focus on 16 states, and then -- if everything breaks right -- get a 17th state that gets you to 270 electoral votes, well, the party is doomed to be a regional party at best. I mean, it's lunacy.

It's New York, California and "pray for Ohio."

Right. Or if the Democratic Party thinks it's only about, "If we can just improve our turnout efforts a little bit more..." Wrong. It doesn't mean that you can't do a better job at turnout. It doesn't mean that we can ignore any part of the Democratic family. But the Democratic Party in this country is no longer the majority party, and a lot of people still act as if we were.

Somehow, we're still the party of the status quo. My starting premise is that I really think we need to change the framing of the political debate, from right vs. left, conservative vs. liberal, to future vs. past. The Democratic Party at its best has always been when it has been about the future.

How do you frame a construction of the Democrats as a party of the future? How do you articulate that to voters?

Part of the way you articulate it is -- Democrats have to be a party that recognizes that, in a global economy, the way America is going to maintain its position in the world is by having the best educated workforce. Democrats should be the party that says America has got to lead the world not only with our military might but with our moral might as well. Democrats ought to be the party that represents innovation, investment in research...

With Democrats, whether it was Roosevelt or Kennedy or Clinton, there was always an aspirational, future-oriented appeal that has been missing. I think Democrats have been recently about protecting against the excesses of where the Republicans are headed. And my feeling is that, right now, there is this moment in time, and part of the moment in time is going to require change by some of us in the Democratic Party.

When you think you're the majority party, you have the luxury of requiring almost a strict orthodoxy: "If you're a Democratic candidate, unless you check every box the right way every time, we're not going to be with you." I think there's a growing recognition that that's the path to success maybe not even in 15 states, let alone 50 states.

Whereas with the Republican Party, until recently, their hard-core, conservative activist base has asked their candidates to pay lip service [to its agenda] but really hasn't asked for results. Well, now that's changing. Whether it's the Schiavo case or those who moved the Senate to the brink on the nuclear option, I think you're seeing it. You're starting to see it on the stem-cell debate. Now there is this move on the Republican side: We're not only going to ask you to have these positions, we're going to ask for action. That suddenly means that perhaps the most vulnerable entity in politics today is not the liberal Democrat but the moderate Republican.

You've said in the past that Democrats can't move forward if every political conversation begins with abortion, God and guns. But the Republicans aren't going to let any conversation begin any other way. How do you break through that?

Well, on guns, I'm a supporter of existing gun laws. I believe in enforcing the existing ones rather than adding a whole lot of new ones. I remember the Washington Post, when I ran [for governor], ran a front-page story, "Warner Goes After Gun Owners, Courts NRA Members." You know, I had an awful lot of my friends in northern Virginia pretty upset with me. But I had, suddenly, a whole lot of folks in three quarters of the rest of the state who were willing to listen to my ideas about education or economic development or about where the future of the communities lies because they said, "We're going to give you a chance."

Is gun control an issue on which Democrats ought to be making moves toward the right?

If you look at [Montana Gov.] Brian Schweitzer, Mike Easley in North Carolina, Joe Manchin in West Virginia, Phil Bredesen in Tennessee, Kathleen Blanco in Louisiana, Kathleen Sebelius in Kansas -- these were candidates who have been reasonable on gun control but who have said, "We strongly support Second Amendment rights." I think there are some in some parts of America, Democrats, who see guns only as an issue that revolves around crime, when in most of America it revolves around culture and home.

And it's easier, politically, for a Democrat to give up on gun control as opposed to, say, abortion rights.

I'm pro-choice, but I've been willing to support parental notification. Many folks in the Democratic Party are concerned that the debate around abortion has moved from a woman's ability to make a decision based on her own religious belief about what to do, about what kind of choice she wants to make -- where I think the overwhelming majority of Americans would still say, you know, we ought to be as much as we can about preventing abortion and we ought to be as much as we can about ensuring that women have adequate healthcare, but that ultimately a woman ought to have that choice. But the debate has moved instead to, in this rare case of late-term abortions, should we have that procedure permitted when it's "life of the mother" or "life and health of the mother"?

And my sense, when I heard President Bush and Senator Kerry debate it, is that that was the distinction they were arguing over! So that debate has shifted, and at some point there may be a shift back. I think the vast majority of Americans do not want to see an overturning of Roe vs. Wade.

This has been [the religious right's goal] for years, but in many ways many of the Republican candidates have paid lip service to that. The right hasn't really asked for action. Now they're saying, "We've got a majority in the House; we've got 55 votes in the Senate; we've got the presidency, and it's not the first year or the first two years; we control every lever of power in the federal government; we have the majority of the governorships; we have the majority of the state legislatures. When are we going to see action?"

And Bill Frist gets all but a really small handful of Bush's judicial nominees confirmed, and he's considered a sellout and a traitor to the cause.

And that orthodoxy is every bit as foreign to where most Americans are as the stereotype of the Hollywood/New York liberal Democrat that also seems out of the mainstream.

How did you position yourself to appeal to rural voters?

The reason I won, going back to the future-versus-past argument -- part of the promise of the global economy, or what we used to call the "new economy," but it's not p.c. anymore, is that you don't need to leave whole communities behind. You can build it anywhere. You don't need to be in the Silicon Valley or northern Virginia or Route 128 in Boston. But that promise has been largely unrealized.

People in rural Virginia haven't felt they have benefited from it?

We have some of the lowest unemployment we've had in decades. But we have not fully cracked the code of, "How do you give that kid in Martinsville, Va., the chance to stay in the community he grew up in?" That is the appeal, and that is the question. And in a lot of ways for Democrats, rural America, small town America, mid-city America, [offer political opportunities]. These are places where people have decided they're going to stay. They're going to stay and they want their communities to flourish, yet they have received virtually no benefits from this current administration. There's not a path that says, "Here's how we're going to make sure your kids get as good an education as the kids in more successful communities. Here's how we're going to make sure we bring jobs back."

That universe of people is there for Democrats to make an appeal to if we can get past some of the cultural issues that just make us seem foreign.

You say that the Bush administration hasn't delivered much to rural America and midsize cities, but the people who live in some of those places might differ. They might say that the Bush administration has kept them safe from al-Qaida and kept homosexual couples from marrying and intruding on their lifestyles.

I'm not sure. I think on the first issue, you're right. Across all of America, urban, rural, suburban, you have concerns about security. I'm not sure on the social issues that that's the first thing people are thinking. I think the first thing they wake up thinking about is, "How is my kid going to get an education that's going to qualify him to get a good job, and are there going to be any of those good jobs in the town here, or is he going to have to move away?"

How do we make sure that there is the kind of quality of life that makes rural America or small-town America appealing? How does it not feel like it is under constant assault, being in effect belittled as not as valid as what we see on the TV set every night?

And how is it that the Republicans -- and this is the Thomas Frank problem -- have succeeded in getting small-town residents so turned around that they end up voting against their own economic self-interests?

I'm not sure they really have.

There was discontent leading up to the 2004 election. Somehow, we didn't have that aspirational, future-oriented, hopeful vision of America -- we didn't lay it out. We laid -- "Here are the programs."

Let me come back to one thing. I've been traveling around the country a lot, and I travel around Virginia a lot. Especially when I'm talking to Democrats, especially with the hardcore Democrats, they want to tell you what they particularly dislike about President Bush. And my feeling is this: There are a lot of things I disagree with the president on. But I think the president's biggest mistake, and I think he's made it twice, once right after 9/11, and once after the Iraq war started, is that he never called on this country for any level of shared sacrifice.

He never called on us to greatness. He never called on us to say, "We are at war, our nation is under assault, and here's what we're going to do." It could be energy independence. It could be "We're going to be the best educated workforce." It could be "We're going to rebuild this infrastructure." It could have been anything. People all across this country were yearning to be called upon. Instead, we were told, "We're going to give a tax cut. We're not going to worry about the nation's finances." And the only people who have been asked to sacrifice are our men and women in the Armed Forces, and they're disproportionately our Guard and Reserve, who make up about 52 percent of our people on the ground in Iraq.

And I think, again, Americans know that. They know that in their gut. Whether it's finances or whether it's, "If we're going to be in this war for some time to come, we're going to have make some level of sacrifice to maintain not only our own national security but our global position in the world." And I think Americans are ready to step up. A little bit of truth telling goes a long way.

You haven't mentioned faith. Not a huge issue in your campaign?

No. I think Democrats need to be able to talk about their faith. I'm a Christian, a Presbyterian. It's part of who I am. But I think that what's become the conventional political wisdom -- that every Democrat has to make sure that they include a Bible verse in every speech -- isn't the case. People want to know who you are. They see that through your faith. They see that through your values. They see that through what you've done in your life, what you emphasize as your priorities.

If there has been a perception that Democrats are somehow anti-faith -- you go back to this notion of the image that has been made of a "national Democrat," which is, you know, intellectual, anti-faith, anti-small town, anti-traditional values. But that doesn't mean that you go from that image to saying that everyone has to start with a quote from the Bible and that we have to lace that through everything we do.

And if Democrats are perceived as anti-faith in some way, then pushing too hard on that front just makes them look phony. Kerry didn't do it well, and Dean doesn't either. So much seems to revolve around personal authenticity -- you were able to sponsor a NASCAR truck as part of your campaign for governor, but if Kerry had done that he would have been the subject of a million more late-night jokes.

I don't know how to say this politely. But in all the things I did in the campaign -- well, I like NASCAR, I like bluegrass. But I didn't try to say, "That's who I am." I didn't suddenly start putting on, you know, cowboy boots and carrying a guitar or wearing camo all the time to show I'm a supporter of sportsmen. I am who I am.

So what are your plans?

Let's make some news this morning!

Break it all right here in Salon.

You know, I want to be part of this debate. If Democrats do not commit to being a national party, competitive everywhere in this country, we do not only our party but our country a disservice. Because even if we elect a president on a 16- or 17-state strategy, we skip two-thirds of this country, and I'm not sure we truly set the agenda.

I've got eight months left in this job. I've got the chairmanship of the National Governors Association. And then I'll have some choices to make. The one option I have that maybe some don't is having had a life before politics in business and the ability to do a lot of things from the private, philanthropic side. That's still an option, too. I wish I had four more years in this job right now, because there are a lot of things we've started in Virginia that won't be fully finished in the four years.

And if you were to run in 2008, are you confident that you can have the kind of discussion you want to have about issues like national security, immigration, Social Security and the like without being diverted by 2008's version of the Swift Boat ads and who flip-flopped about what?

What we've got to have -- you're going to need positions. You're going to need well-thought-out positions. But you're also going to need two or three ideas that capture the imagination. In 2004, out of both those campaigns, you didn't hear many of those ideas.

I'm thinking of Clinton in 1992, with the notion of national service. He mostly never implemented it, but it captured people's imagination. There was Bush's idea in 2000 of a compassionate conservatism, and to a degree the faith-based stuff. I'm not saying I agreed with it, but it captured people's imagination: Is there a different way to help people who are less fortunate in our society?

When I talk to folks, I go through some of the things we're doing in Virginia, whether it's changing the incentive system for teachers, whether it's making sure a student can gain a semester's worth of college credit in high school, whether it's guaranteeing a kid who's not going to college an industry certification along with a high school diploma if they meet certain criteria. I'm not sure that any of those are big enough ideas, but they're the kinds of things that people go away saying, "There's an idea there." Democrats ought to be about percolating a lot of these ideas, about capturing some of these ideas.

Does putting out those kinds of specific ideas help you get through the noise?

If the Democrats are not simply about protecting existing government programs, no matter how good those programs may be, but instead are about a new idea about how your kid's going to get a better education, or about how your mom or dad is going to be taken care of on a long-term care basis, or about how your family is going to be able to give a son a minimum healthcare benefit package that doesn't break their bank or the employer's bank, or just a notion of how we're going to put rural values back in, where you don't have to move away to find that job, so you can do it in rural America, in a small midsize city -- in a way, the idea's important, but equally important is that you're talking about the future. You're talking about an aspiration. You're talking about giving people hope.

Shares