On Monday, Oct. 5, at an elementary school in Washington County, Ark., Will Phillips, a precocious 10-year-old who had been promoted from third to fifth grade, refused to join his class in standing and reciting the Pledge of Allegiance. His parents have gay friends, and Will claimed that the denial of gay marriage means that the U.S. lacks “liberty and justice for all.” After refusing to recite the pledge for several days, the boy was sent to the principal’s office when he told his teacher, “With all due respect, ma’am, you can go jump off a bridge,” a sentiment shared by many 10-year-olds who are not political activists.

Flaps over the Pledge of Allegiance occur with dreary regularity. In 2000 Michael Newdow, an atheist and the parent of a child in California’s public schools, filed a lawsuit claiming that the pledge was unconstitutional because of its inclusion of the phrase “under God.” He won in federal circuit court, but in 2004 the Supreme Court chickened out and, to avoid addressing the issue, tossed out the case on the argument that as a noncustodial parent he did not have standing to sue. Newdow is a party in a subsequent case that is working its way through the courts. Back in 1940, the Supreme Court ruled that Jehovah’s Witnesses could be forced to recite the pledge, and then, in 1943, in the midst of a war against totalitarian states, the court reversed its earlier opinion.

Individuals like Phillips and Newdow who publicly challenge the Pledge of Allegiance can expect to provoke not only harassment by their neighbors but also cyclones of bloviation emanating from elected leaders who, unwilling to fix healthcare or pay for infrastructure, always have time to defend the pledge or the flag. In response to the Newdow case, 150 members of Congress gathered on the steps of the Capitol to recite the pledge, stressing “under God.” To show its understanding of the phrase “liberty and justice for all,” the Republican-controlled House in 2004 passed a law stripping the federal courts of jurisdiction in cases involving the pledge; the bill died in the Senate, proving that the system of checks and balances sometimes succeeds in its intended function of thwarting mob rule.

Ironically, the Pledge of Allegiance, which today is most fiercely defended by white conservative Southerners whose Confederate ancestors tried to destroy the United States in the 1860s, was written by a Yankee socialist from New York in the 1890s. Francis Bellamy was a progressive Baptist minister and a Christian socialist who composed the pledge for the 400-year Columbus anniversary in 1892 and published it in a youth magazine. His cousin Edward Bellamy, a socialist from Massachusetts (Glenn Beck, are you taking notes?), was the author of the 1888 bestselling utopian novel “Looking Backward: 2007-1887,” which described a collectivist America in 2007 in which everyone is drafted in an “industrial army” and dines in public kitchens. (Instead of an industrial army, the United States in 2007 had a reserve army of the unemployed and working poor, and instead of public kitchens we had Starbucks.)

The Bellamys, like many at the time, were inspired by the integral nationalist and statist ideals that were percolating in Europe. From the 1890s until the 1940s, American schoolchildren often accompanied recitation of the pledge with “the Bellamy salute,” a stiff-armed salute of the ancient Roman kind that was indistinguishable from the later fascist and Nazi salutes. Heil Amerika! It was Franklin Roosevelt who suggested replacing the salute with a hand over the heart.

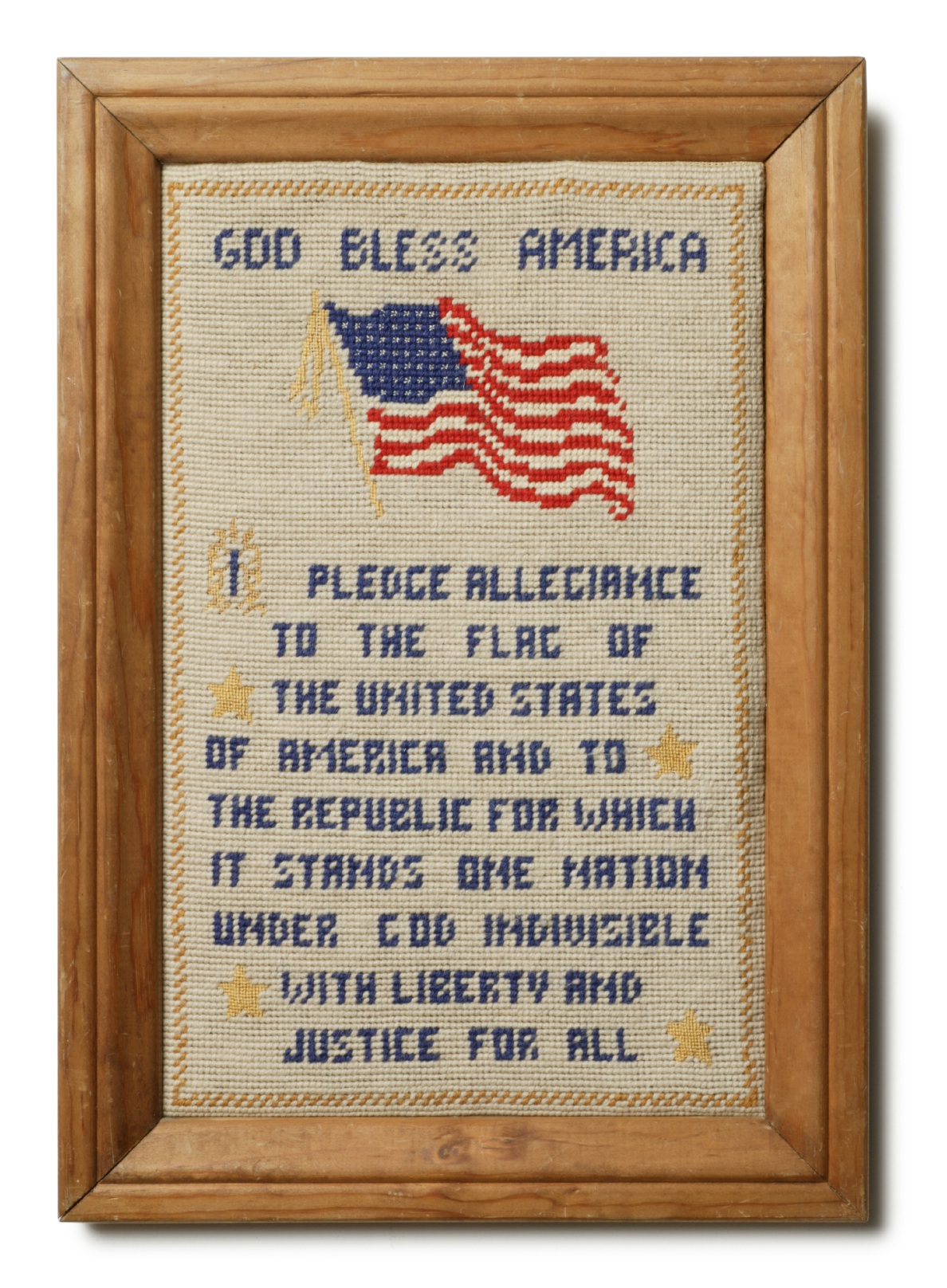

In the course of the 20th century, support for the pledge migrated from the collectivist left to the reactionary right. The original Bellamy pledge read: “I pledge allegiance to my flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation indivisible with liberty and justice for all.” In 1923 WASP nativists prevailed in having “my flag” replaced by “the flag of the United States of America,” to make sure that young Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, among others, knew they weren’t pledging allegiance to the old country. In 1954, Congress inserted the words “under God,” following an influential sermon by a Protestant pastor who argued that the model for the United States in the Cold War should be ancient Sparta.

Could anything be more foreign to America’s enlightened 18th-century liberal and republican traditions than this toxic compound of collectivism, nativism, Spartan militarism and theocracy?

The very idea of a pledge of allegiance, in any form, is completely at odds with what is often called “the American Creed,” inspired by the 17th-century philosopher John Locke’s theory of natural rights and government by popular consent. The concept of “allegiance” is feudal. In medieval Europe, the liegeman, or subject, pledged allegiance to his liege lord. But in Lockean America, there is no government outside of society to which the members of the society could pledge allegiance, even if they wanted to. As the scholar Mark Hulliung explains Lockean liberal theory in “The Social Contract in America: From the Revolution to the Present Age” (2007):

There is a social contract by which the people bind themselves to one another, but no subsequent political contract [between people and government]. The rulers hold power temporarily, as mere “trustees” of the people … What the people give they can take away whenever they please, because they are bound by no contract between governors and governed.

In a republic, the people should not pledge allegiance to the government; the government should pledge allegiance to the people.

If we Americans as individuals do not owe personal allegiance to federal, state and local governments, in the way that medieval subjects owed personal allegiance to feudal lords and kings, then what is the basis of our obligation to obey the laws? The answer is that as members of the sovereign people we owe each other an obligation to obey the rules that we, directly or through elected representatives, have mutually agreed on. The members of a condo association agree with each other to obey the rules they ratify. Part of their mutual obligation involves carrying out the legitimate instructions of the manager whom they have hired. But while the members of the association may agree to obey directions from their common employee, no condo association pledges allegiance to the condo manager. The principal does not swear to serve the agent.

From this it follows that the appropriate expression of patriotism in a democratic republic is not a hierarchical, or “vertical,” pledge of allegiance but a fraternal/sororal, or “horizontal,” pledge of mutual support. As it happens, we have an example of such a pledge: the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson’s famous preamble restates the Lockean theory of popular sovereignty:

That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundations on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

Having begun the Declaration with the statement that government is merely a tool created to serve the people, the signers could have hardly concluded with a feudal oath of fealty to the political artifact they themselves had constructed. That would make about as much sense as pledging obedience to your refrigerator or your cellphone. Instead, they made a pledge to one another: “And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.”

While a pledge of allegiance by the subject to the government is incompatible with American republican principles, a voluntary pledge of mutual support among the people who collectively create and own the government might be useful, if only as a succinct catechism of the American Creed. If we drop the strained and unnecessary language about “their Creator” and “divine Providence,” designed to offend neither Christians nor 18th-century Deists, and replace the topical phrase “this Declaration” with a reference to the enduring principles of republican liberty, we might get something like this:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundations on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. And for the support of these principles, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Call this purely voluntary pledge the Citizens’ Pledge of Mutual Support for the Principles of the Declaration of Independence, or simply, the Citizens’ Pledge. It would be addressed by Americans directly to one another, rather than to the flag or any other symbol of the state. Oh, and if you give a stiff-armed salute, you’ll be sent to the principal’s office.