In a few weeks, the second decade of the 21st century will be upon us. (Note to purists who insist that it will begin on Jan. 1, 2011: Get a life.) The first decade of this century is likely to be remembered as the Decade From Hell. It began with a stock market crash and the 9/11 attacks. It ended with the greatest global economic crisis since the Great Depression and deepening U.S. military involvement in Afghanistan and Pakistan. A decade's worth of stock market gains were swiftly erased and for 10 years there has been no new net job creation outside the areas of healthcare, education and government.

The oughts can't end a moment too soon.

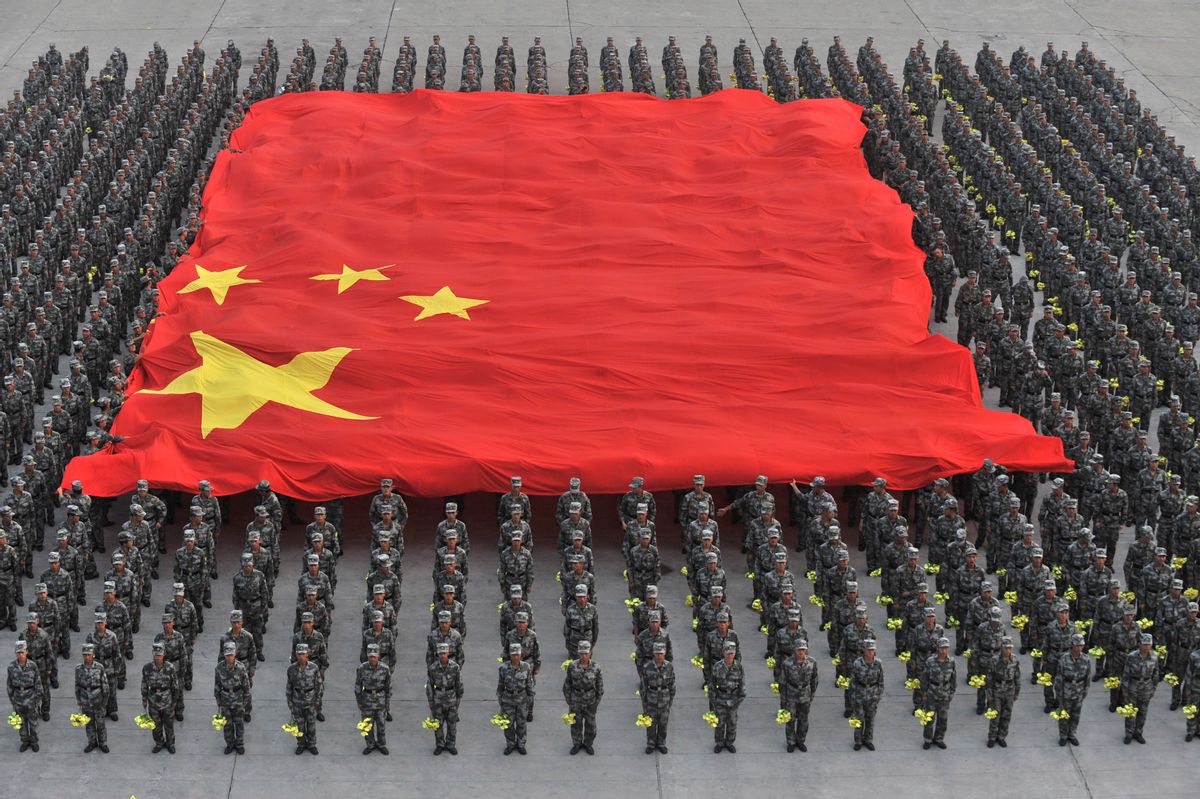

What does the decade of 2010-20 hold in store? There is already a consensus among America's commentariat. We are told that the near future will see the decline of the United States and the rise of China in global power politics and, as an added attraction, the decline of the nation-state.

Yeah, sure. I'll believe it when I see it.

I've heard it before. Born in 1962, I have followed the public discussion in this country for nearly half a century. And as I think back on the five decades of my life to date, what impresses me is the repetition of two themes in public discourse: the dramatic rise and fall of the U.S. and other great powers, and claims of radical changes in the very nature of world politics. When I hear these same sensational themes recycled, my response is a yawn.

Take the rise and fall of the great powers, a subject that has engaged me since I took Paul Kennedy's course on the subject at Yale in the 1980s. I have lived through enough cycles of exaggeration to be skeptical about claims that radical changes in the global distribution of power and wealth will end American primacy in the near future. In the 1970s, the Soviets were supposed in some quarters to be on the verge of surpassing the U.S. not only in military strength but also in economic power. Then the Soviet empire fell apart, and it turned out that CIA analysts and other alleged experts had grossly exaggerated the size of the Soviet economy and the efficiency of the Soviet armed forces.

But the theme of the imminent downfall of the U.S. was too good to be abandoned. So a substitute was found for the Soviet leviathan in the Japanese juggernaut. In the 1980s, there were predictions that Japan might actually surpass the U.S. in gross domestic product by 2000. Tom Clancy wrote a novel in which Japanese militarists blow up the U.S. Capitol and slaughter America's top leaders. Business school gurus recommended Japanese management techniques like singing company songs. And then the bottom fell out of the Japanese real estate and stock markets and Japan went into a prolonged slump from which it has yet to recover.

In the 1990s, American pundits lurched to the other extreme. Following the implosions of the Soviet Union and Japan, America's best and brightest declared almost unanimously that the U.S. was not a declining empire after all. No, America was an unstoppable super-duper-hyper-megapower! U.S. victories in a couple of wars in which a military designed to defeat the Warsaw Pact was deployed to crush bankrupt, backward countries like Iraq, Serbia and Afghanistan were interpreted as proof that the world -- and not just bankrupt, backward countries -- trembled before the might of Washington's legions. Otherwise sensible people, swept up in the conventional wisdom, wrote things like, "Not since Rome has a single state been as powerful as the United States of America."

This neo-imperial triumphalism shaped U.S. policy during the Bush years, when Donald Rumsfeld's Defense Department, in the silliest government seminars of all time, invited historians to speculate on lessons for the Pax Americana from ancient empires. Let's combine Byzantine diplomacy with Hittite battlefield tactics ...

Then it turned out that a handful of terrorists hijacking airplanes could temporarily crater the U.S. economy and make Americans afraid of their own shadows, while small numbers of insurgents with improvised explosive devices (IEDs) could make American occupations of other countries too costly for the American people to stomach. So much for the greatest empire since Rome. The imaginary Pax Americana was as short-lived as the imaginary Pax Nipponica and the imaginary Pax Sovietica that preceded it.

The lesson I take from all of this is that the distribution of power and wealth in the world is far more stable than you would think if you listened to our manic-depressive public discourse, where America is always either on the brink of catastrophic decline or unchallengeable global supremacy. The U.S. share of global GDP -- a good proxy for power -- has fluctuated around a quarter or a fifth since the early 1900s, with the exception of a temporary spike after World War II before the other industrial great powers recovered from it. The Soviet Union never came anywhere near challenging American primacy, and neither did Japan.

But now we are told that China will catch up with the U.S. in a couple of decades and dominate the world in the "Asian century." Maybe, and then again, maybe not. Those projections depend on straight-line extrapolations of the incredibly high Chinese growth rates of the last decade. But there are a lot of problems with those projections that you seldom hear in awed discussions of the rise of China.

For one thing, as developing countries become developed countries, their initial high rates of growth slow down. Taking this into account pushes China's parity with the U.S. further into the future. And this assumes that China's high growth rates have been real. More and more experts are wondering whether those official growth rates can be trusted. It would not be the first time that a corrupt, authoritarian regime cooked the books. If China's growth figures have been inflated for a decade or two, then the Chinese economy may be smaller than many believe and the distance it has to travel to catch up with the U.S. is much greater.

And even optimistic projections only have China catching up with the U.S. in overall GDP, mainly because it will have a larger, but much poorer, population. Nobody expects China, even under the most favorable circumstances, to catch up with the U.S. and other developed countries in per capita income until the 22nd century, if then. And each of the rest of the "BRICs" (Brazil, Russia, India, China) is dwarfed by the U.S. in GDP.

But don't expect to read any of this in the newsmagazines or the Op-Ed columns. "Sleeping Dragon Wakes, World Trembles" or "South Asian Elephant Shakes World Order" make better headlines than "Even With High Growth, China and India Will Be Poor for Generations."

Hyperbolic assertions about America's meteoric rise or meteoric decline are not the only kind of hype that pollutes public discourse. Academics and journalistic pundits alike are fond of drawing attention to themselves by declaring that we are on the verge of a radical transformation of the system of sovereign states that has existed in Europe since the Thirty Years' War and in the world since post-World War II decolonization. Once again, we see the fallacy of the straight-line extrapolation from a temporary trend to a cosmic transformation.

In the 1990s, some misinterpreted the disintegration along ethnonational lines of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia. Instead of understanding these phenomena as what they were -- the long-delayed dissolution of remnants of the Romanov and Hapsburg empires -- these local breakups were said by some to augur the crackup of states everywhere.

During the Balkan wars in the mid-1990s, on a trip to war-ravaged Croatia, I sat on a plane next to an American businessmen who was reading a pop futurist book. "This book says that by the year 2000, there will be 3,000 nations in the U.N.," the businessman told me. When I expressed my skepticism, he evidently concluded that I didn't know what I was talking about and said little for the rest of the flight. As of 2009, mostly as a result of the Soviet and Yugoslav crackups, a couple of dozen new states have joined the international community since the end of the Cold War, but not a couple of thousand.

Others in the 1990s predicted not the exponential multiplication of states but the end of the state as such as the dominant actor in world politics. Robert Kaplan predicted "the coming anarchy" and many prophesied a neo-feudal world order in which stateless entities were more powerful than conventional states.

9/11 gave a brief boost to those who claimed that international terrorist organizations now rivaled states in their power, but in retrospect it was a fluke, not a trend. Since 9/11 the U.S. and other states, having heightened their security, have thwarted mass-casualty attacks, and jihadists have been limited to crude, smaller-scale violence like machine-gunning crowds and blowing up buses and trains. Contrary to popular belief, with the exception of jihadism and a few local wars of partition, political violence worldwide dramatically diminished after the Cold War and remains low compared to the Cold War years (in part because the U.S. and the Soviets stirred the pot of many local conflicts that mercifully fizzled out without external intervention).

And the international corporations that were supposed to be more powerful than countries? The poorest countries have to bargain with transnational enterprises and banks -- but that is nothing new. Not only giant but also medium-size countries still overmatch even the largest corporations and banks. And "global" firms turned out to be not so global. When the present economic crisis struck in 2008, allegedly transnational enterprises like banks and car companies went running for aid to their respective national governments. These global firms, from Deutsche Bank to General Motors, have always been deeply rooted in particular nation-states, notwithstanding their overseas subsidiaries and partners. True global capitalism is a myth spread by the likes of Thomas Friedman. In reality, we live in the era of multinational capitalism, not global capitalism.

While we are strolling down memory lane, remember all the chatter a few years back about how irresistible immigration flows were leading to a world with open borders for labor as well as goods and capital? One of the fads in universities in the 1990s was the claim that "diasporic consciousness" was leading to the replacement of national identity by post-national global multiculturalism.

Not hardly. The backlash against the economic and cultural problems associated with mass immigration has forced parties of the left as well as the right in Europe to crack down on illegal immigration and asylum seeking. In the last decade in the U.S., many Democratic politicians who face reelection, including President Obama, have switched from denouncing critics of illegal immigration as racists to boasting of the success of their efforts to control the borders and promising to exclude illegal immigrants from public healthcare plans. And from India and Saudi Arabia to America's Southwestern border, fences are going up, to keep out both terrorist infiltrators and the unwanted foreign poor.

Remember how national identity was supposed to wither away? Obama campaigned and now governs against a backdrop of multiple American flags, as though he were the head of the John Birch Society. In Britain, the Labour Party that touted the wonders of globalization and financial deregulation in the 1990s is now proposing citizenship tests for immigrants, assimilation and American-style civic patriotism or liberal nationalism. The nation-state is not withering away. Post-national globalism is withering away. To be more accurate, post-national globalism never really existed, except in the imaginations of pundits and professors and plutocrats who concluded that the nation-state was dead because they invested in China, bought their suits in London and watched French art films.

In the decade about to begin, it would be naive to expect an end to breathless hype about world politics. That sort of thing wins readers for journals and newspapers and makes the careers of pundits who aspire to bloviate at Davos before an audience of the trendy rich. Nevertheless, the appropriate response to claims that America is about to collapse or conquer the world, and to assertions that the nation-state system is about to give way to something entirely different -- global mafias, city-states, a new Caliphate, tribal empires, a cybernetic Singularity, whatever -- is a bored yawn.

Shares