Shortly after the volcano in Iceland polluted the skies over Europe, and while the British Petroleum oil spill contaminated the Gulf of Mexico, Rand Paul dumped the intellectual equivalent of toxic pollution into the world of public discourse by claiming that it was wrong for the Civil Right Act of 1964 to outlaw segregation in private facilities.

Had this come from former KKK leader David Duke it would not have been news, but it made headlines, coming as it did from the winner of the Kentucky Republican Senate primary, the son of libertarian cult hero Rep. Ron Paul of Texas and a tribune of the Tea Party movement. According to the younger Paul, "the hard part about believing in freedom" is that while it was all right for the 1964 Civil Rights Act to outlaw racial discrimination by public entities, it was tyrannical for the federal government to require businesses like restaurants, hotels and stores to serve non-white customers.

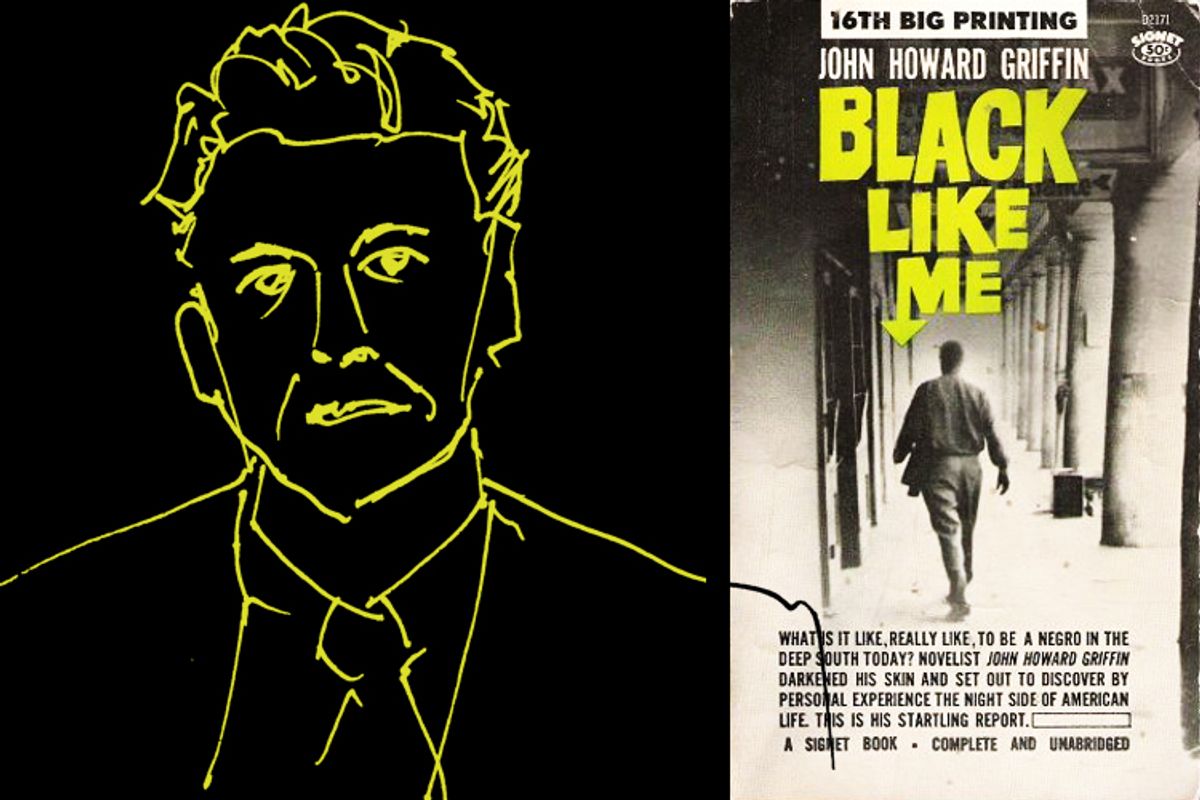

As a native of Texas, where white-only businesses were legal until the Civil Rights Act passed, where interracial marriage was illegal until the Supreme Court issued its holding in Loving v. Virginia in 1967, and where private racial discrimination in housing was legal until President Johnson pushed through one of his personal obsessions, the Fair Housing Act of 1968, I can suggest a book that Rand Paul and like-minded libertarians really ought to read: John Howard Griffin's "Black Like Me."

Griffin, a native of Dallas, was at different stages in his polymathic career a decorated combat veteran in World War II, a music teacher, a philosopher, a novelist and a convert to Catholicism. In 1959, with the help of a dermatologist in New Orleans, this white Southerner had his skin darkened so that he could try to understand what black people experienced in the segregated South. Published in 1961, "Black Like Me" was the book that emerged from his journal entries. It became a best-seller and made Griffin (who was portrayed by James Whitmore in a 1964 movie adaptation) an international celebrity.

It also made him, his elderly mother and wife and children the targets of threats, including a public hanging in effigy in the town where he lived at the time, Mansfield, Texas. For a while, the Griffins and their children found safety by living in Dallas with Decherd Turner and his wife, Martha Anne (who were close friends with my family in later years). Before becoming one of the world's greatest librarians, running first the Bridwell Library at Southern Methodist University and then the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Turner had grown up on a small farm in Missouri, where every Christmas morning his father forced the family to gather on the front porch of the farmhouse while he fired a round into the sky shouting, "God bless Jefferson Davis!" Inheriting the ebullience of his father while rejecting the politics, Turner shared Griffin's strain of defiant Southern liberalism. His typically fearless response to the threats against his friend was to offer him not only his home but also an office and a public lecture at SMU.

Having been forced out of his home and his town and into hiding by white supremacists, Griffin had no patience for the kind of sophistry employed by people like Barry Goldwater and Rand Paul, who argue that, while they are personally opposed to private sector racism, they believe that a commitment to individual liberty requires us to tolerate racial discrimination by private businesses, but not by public agencies.

On rereading "Black Like Me" with Rand Paul's controversial comments in mind, I was struck by how very few truly public places there were in the apartheid South. Employers, subdivisions, stores, restaurants, gas stations, hotels -- Rand Paul would have allowed all of these to be segregated to this day because they are privately owned. According to this disingenuous theory, in the segregated South everyone, black or white, should have had a right to work, eat and sleep at the small-town post office or police station, because they were public agencies -- but no right to work, eat or sleep anywhere else.

Private employment? Disguised as a "Negro," Griffin tried to get a job at a plant in Mobile, Ala., by offering to accept less pay than a white man would:

"No use trying down here," he said. "We're gradually getting you people weeded out from the better jobs at this plant. We're taking it slow, but we're doing it. Pretty soon we'll have it so the only jobs you can get here are the ones no white man would have."

"How can we live?" I asked hopelessly, careful not to give the impression I was arguing.

"That's the whole point," he said, looking me square in the eyes, but with some faint sympathy, as though he regretted the need to say what followed: "We're going to do our damndest to drive every one of you out of the state."

Private real estate transactions? Until struck down by federal law, restrictive covenants barring homeowners from selling to blacks, Latinos and sometimes Catholics and Jews were common in every region of the country. Griffin tells the story of a talk he gave at a college where an industrial psychologist was the only black in attendance. A white college professor, proud of his paternalistic liberalism, asked the black doctor of industrial psychology whether he considered the lecture a turning point in the community's history, and was shocked to be told no:

The doctor said, "It's true that I have a good job in this town, and I seem to be respected, and I am certainly paid a wage commensurate with my skills. But -- so long as I have to house my wife and children in a town twenty miles away because I can't buy, rent, lease or build a home here, don't expect me to get too excited over your 'historic turning points.'"

Privately-owned stores?

No matter where you are, the nearest Negro café is always far away, it seems. I learned to eat a great deal when it was available and convenient, because it might not be available or convenient when the belly next indicated its hunger ... It is not that they crave service in the white man’s café over their own -- it is simply that in many sparsely settled areas Negro cafes do not exist; and even in densely settled areas, one must sometimes cross town for a glass of water. It is rankling, too, to be encouraged to buy all of one's goods in white stores and then be refused soda fountain or rest-room service.

Rand Paul is a year younger than I am, born like me in Texas during the final years of segregation. I have difficulty believing that any white Southerner my age who questions the civil rights laws that broke down the all-encompassing system of "private" economic and social segregation in our native region does so purely out of libertarian principle. I would have trouble believing that, even if not for recent revelations that his father’s supposedly libertarian newsletter for decades was filled with unsigned racist rants.

I have known and worked with many conservatives and libertarians in my life, and in my experience states' rights arguments and libertarian arguments against the Civil Rights, Voting Rights and Fair Housing Acts are used opportunistically by people who are covert, if not overt, bigots. You do not have to be a racist to oppose race-based affirmative action, a form of compensatory discrimination that Bayard Rustin, the organizer of the March on Washington, opposed as a violation of the nondiscrimination principle. But if it bothers you that cafeterias and stores and hotels and gas stations since 1964 had been unable to refuse service to blacks, or Latinos, or Asians, then you cannot complain if people speculate about your motives. I do not believe it is possible for anyone to be "personally" opposed to racism and at the same time opposed on the grounds of high constitutional principle to public policies that eliminate private policies constituting an elaborate, interlocking system of racial apartheid. That position may be theoretically coherent. But it is psychologically impossible.

In "Black Like Me," Griffin writes that "the most obscene figures are not the ignorant ranting racists, but the legal minds who front for them, who 'invent' for them the legislative proposals and the propaganda bulletins. They deliberately choose to foster distortions, always under the guise of patriotism, upon a people who have no means of checking the facts."

John Howard Griffin did not live to see the rise of Ron and Rand Paul. But he knew their kind all too well.

Michael Lind is policy director of the Economic Growth Program at the New America Foundation and author of "The American Way of Strategy."

Shares