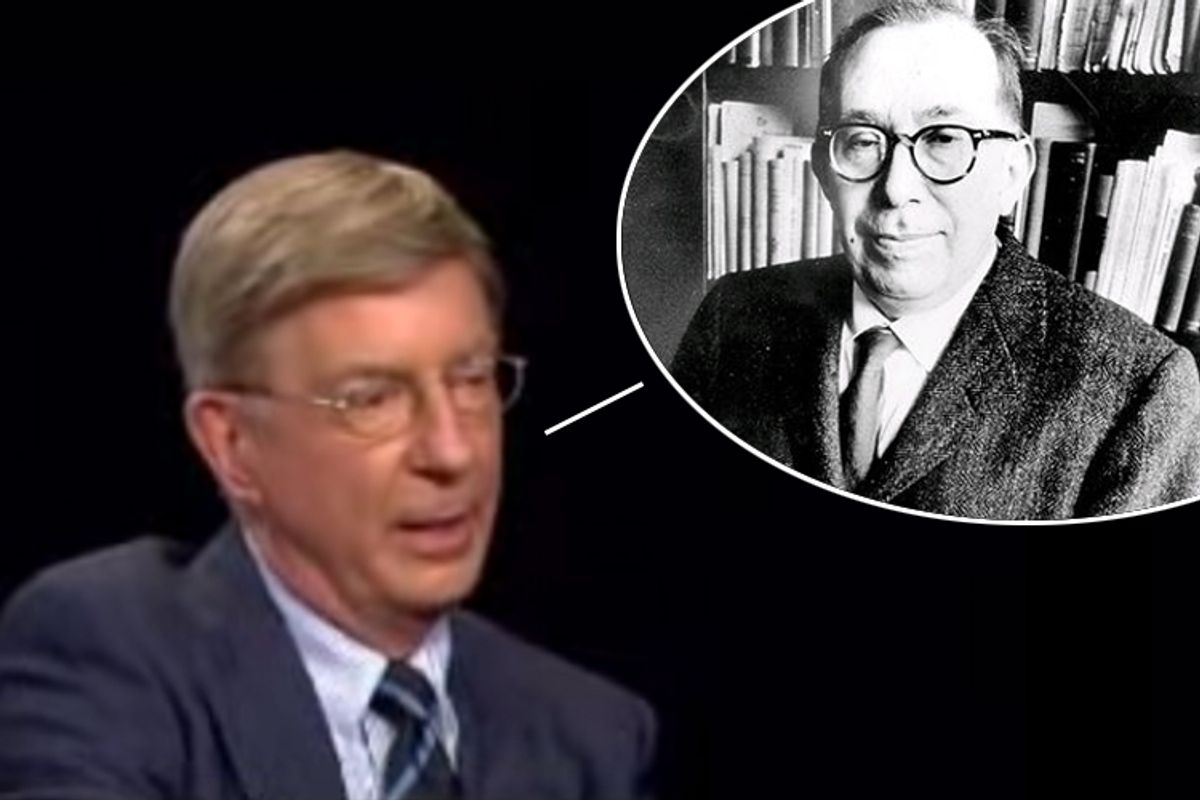

Have American progressives rejected the belief in natural rights that inspired the American Founding, in order to worship History with a capital "H" while putting as many of their fellow citizens as possible on the dole? That's the claim of the small group of followers of the late philosopher Leo Strauss who have become Glenn Beck's historians. Now the columnist George Will, who should know better, has joined the television demagogue Glenn Beck in the Orwellian project of rewriting American history in order to demonize liberalism.

In a review of "Never Enough: America's Limitless Welfare State" by William Voegeli, editor of the Claremont Review, Will endorses the outlandish claims of the Straussian school. According to Will, we must choose between "two Princetonians -- James Madison, class of 1771, and Woodrow Wilson, class of 1879." Madisonian conservatives believe that government should "protect the exercise of natural rights that pre-exist government, rights that human reason can ascertain in unchanging principles of conduct and that are essential to the pursuit of happiness." In contrast, Wilsonian progressives believe that History with a capital "H" "rather than nature, defines government's ever-evolving menu of rights -- entitlements that serve an open-ended understanding of material and even spiritual well-being."

If Will and Voegeli are to be believed, Franklin Roosevelt and "Lyndon Johnson, an FDR protégé," both "repudiated the Founders' idea that government is instituted to protect pre-existing and timeless natural rights, promising 'the re-definition of these rights in terms of a changing and growing social order ...'" The result of this repudiation of natural rights by American liberals, Voegeli writes, is a welfare state "blanketing the skies with crisscrossing dollars." According to Voegeli, "Lacking a limiting principle, progressives cannot say how big the welfare state should be but must always say that it should be bigger than it is."

Will and Voegeli repeat two now-familiar claims of Straussian propaganda. First, FDR, LBJ and modern liberals have rejected the idea of "pre-existing and timeless natural rights." Second, they have favored putting as many people as possible on the dole. The historical record makes it clear that both accusations are libels.

It is true that Woodrow Wilson, like many other political scientists in the early 1900s, was influenced by German scholarship that emphasized cultural and social evolution and rejected the Lockean tradition of natural rights liberalism as outmoded and "Newtonian." But as Derek Webb points out in an important essay titled "The Natural Rights Liberalism of Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Economic Rights and the American Political Tradition" (2007): "Roosevelt, unlike many of his Progressive predecessors, self-consciously grounded his defence of economic rights in the philosophical, historical, and constitutional principles of early American liberalism."

Was Roosevelt repudiating the American Founding when he told Democrats in Philadelphia in 1936: "This is fitting ground on which to reaffirm the faith of our fathers; to pledge ourselves to restore to the people a wider freedom; to give to 1936 as the founders gave to 1776 -- an American way of life." The goal of the New Deal, he explained, was "to preserve to the United States the political and economic freedom for which Washington and Jefferson planned and fought." What do George Will and William Voegeli think that FDR meant by "reaffirm," "restore" and "preserve"?

Was Hubert Humphrey at the 1948 Democratic national convention repudiating the ideals of the Declaration of Independence when he helped provoke a walk-out by Southern segregationists who opposed the party's civil rights plank? "To those who say, my friends, to those who say, that we are rushing this issue of civil rights, I say to them we are 172 years too late! To those who say, this civil rights program is an infringement on states' rights, I say this: the time has arrived in America for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states' rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights!" If George Will and William Voegeli do the math, they will discover that 172 years before 1948 was ... 1776.

Do the Straussians believe that Martin Luther King, Jr. repudiated the ideals of the Declaration of Independence? In his "Letter From the Birmingham Jail" in 1963, he wrote: "Was not Abraham Lincoln an extremist -- 'This nation cannot survive half slave and half free.' Was not Thomas Jefferson an extremist -- 'We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.'" At the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August of that year, King famously said: "I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed -- we hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal."

Will and Voegeli imply that when Roosevelt spoke of renegotiating the social contract to acknowledge new economic rights, he was throwing out the previous American understanding of natural rights. This is a deliberate misreading of what FDR said. Roosevelt observed: "We have come to a clear realization of the fact that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence." Far from being heretical, Roosevelt's sentiment was taken for granted by early American statesmen like Jefferson, whose goal of "economic security and independence" was promoted by encouraging the ownership of small farms and pre-industrial shops.

Roosevelt argued that small-government Jeffersonianism made sense in a society of farmers: "The happiest of economic conditions made that day long and splendid. On the Western frontier, land was substantially free. No one, who did not shirk the task of earning a living, was entirely without opportunity to do so." Industrialization and urbanization, however, made a new "economic constitutional order" necessary, if the unchanging ideals of the American revolution were to be achieved in modern conditions.

The goal of the New Deal was, among other things, to save the relatively recent innovation of large-scale corporate capitalism, which was unknown to the Founders: "We did not think because national government had become a threat in the 18th century that therefore we should abandon the principle of national government. Nor today should we abandon the principle of strong economic units called corporations, merely because their power is susceptible of easy abuse." This is not the language of a radical, and indeed FDR told the Democratic State Convention in Syracuse, N.Y., in 1936: "The true conservative seeks to protect the system of private property and free enterprise by correcting such injustices and inequalities as arise from it. The most serious threat to our institutions comes from those who refuse to face the need for change. Liberalism becomes the protection for the far-sighted conservative ... I am that kind of conservative because I am that kind of liberal."

The Straussian claim that American liberals since the New Deal have repudiated the ideals of the Declaration of Independence, then, is nothing more than a smear, like calling Barack Obama a socialist or fascist. What about Voegeli's claim, seconded by George Will, that liberals have a limitless appetite for addicting Americans to welfare?

Here, too, the historical record contradicts right-wing propaganda. Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson detested what both called "the dole." In 1935 FDR asked Congress to replace relief payments with public employment programs:

The lessons of history, confirmed by the evidence immediately before me, show conclusively that continued dependence upon relief induces a spiritual and moral disintegration fundamentally destructive to the national fibre. To dole out relief in this way is to administer a narcotic, a subtle destroyer of the human spirit. It is inimical to the dictates of sound policy. It is in violation of the traditions of America. Work must be found for able-bodied but destitute workers. The Federal Government must and shall quit this business of relief.

I am not willing that the vitality of our people be further sapped by the giving of cash, of market baskets, of a few hours of weekly work cutting grass, raking leaves or picking up papers in the public parks. We must preserve not only the bodies of the unemployed from destitution but also their self-respect, their self-reliance and courage and determination.

Like his mentor Franklin Roosevelt, Lyndon Johnson, who headed the National Youth Administration work program in Texas in the 1930s, supported workfare, not welfare, for the able-bodied poor. Describing the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, which promoted jobs and training for the poor, Johnson said: "This is not in any sense a cynical proposal to exploit the poor with a promise of a handout or a dole. We know -- we learned long ago -- that answer is no answer ... We are not content to accept the endless growth of relief rolls or welfare rolls." When the bill was being drafted, Johnson ordered one aide, Lester Thurow, to remove any cash support programs, and told another aide, Bill Moyers, "You tell [Sargent] Shriver, no doles."

The Rooseveltian liberal preference for public jobs over cash grants for the poor was shared by the patron saint of natural rights liberalism, John Locke, who in the 1690s proposed that the deserving poor be employed at public expense. Will and Voegeli to the contrary, liberals in the Rooseveltian tradition have always favored public work programs like Roosevelt's Works Projects Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps and Johnson's Job Corps and Volunteers in Service to America as an alternative to welfare payments to poor people able to work. It is conservatives who have consistently opposed public work programs. When FDR's National Resources Planning Board in 1943 proposed using a permanent public works program as an alternative to cash relief after the war, conservatives in Congress killed the agency and buried the report. In 1984, when Congress, led by Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York, created the American Conservation Corps, modeled on the Depression-era CCC, President Ronald Reagan vetoed the bill.

Reagan's veto was ironic, because in the 1930s his father, Jack Reagan, had been the head of the WPA in Dixon, Ill. Reagan remembered the WPA fondly: "Now, a lot of people remember it as a boondoggle and ... raking leaves ... Maybe in some places it was. Maybe in the big city machines or something. But I can take you to our town and show you things, like a river front that I used to hike through once that was swamp and is now a beautiful park-like place built by WPA."

It is true that in his 1972 presidential campaign, George McGovern supported the idea of a guaranteed income or "demogrant," a proposal that Johnson had rejected. But the idea of a guaranteed income or negative income tax was proposed by none other than the libertarian economist Milton Friedman in the conservative magazine National Review in 1967. After defeating McGovern, Nixon adopted the negative income tax as his own proposal. When it was rejected by Congress, a modified version of the negative income tax in the form of the Earned Income Tax Credit became the preferred welfare program of the Ford and Reagan administrations and of Bill Clinton, a center-right Democrat who broke with the New Deal tradition on this as on other subjects. Recently, Charles Murray wrote an entire book proposing to replace welfare programs with a guaranteed income.

What accounts for the infatuation of conservatives like Milton Friedman and Charles Murray with giving cash to the poor instead of providing them with public works jobs like the WPA job that rescued Reagan's father from unemployment in the Great Depression?

Friedman and most other economists on the American right, like neoclassical economists in general, do not think about the economy as Roosevelt and Johnson did, in terms of republican citizenship and the dignity of labor. Chicago School economists are utilitarians. For them, poverty is by definition a lack of money and the simplest way to cure it is to write checks to the working poor or the non-working poor. Writing checks involves less bureaucracy than public works programs that add to our national infrastructure or increase our quality of life. The Lockean republican objection of Roosevelt to cash relief -- "We must preserve not only the bodies of the unemployed from destitution but also their self-respect, their self-reliance and courage and determination" -- is alien to the value system of utilitarian economics.

Of course there are reasons other than ideology why conservative elites prefer a negative income tax to public jobs programs or a higher minimum wage. The guaranteed income, like the earned income tax credit, functions as a subsidy to the employers and customers of low-wage labor. These programs obey the First Commandment of Crony Conservatism: privatize the benefits while socializing the costs. The EITC is a massive subsidy of businesses and consumers in the low-wage South by American taxpayers in other regions. That is why the EITC has been the favorite antipoverty program not only of conservatives but also of center-right Democrats from the South like Bill Clinton, Lloyd Bentsen and Russell Long.

This strategy of direct or indirect taxpayer subsidies for starvation-wage enterprises is the opposite of the one announced by FDR in 1933: "No business which depends for its existence on paying less than living wages to its workers has any right to continue in this country." While acknowledging a minor role for a limited EITC, liberals in the New Deal tradition prefer a combination of a living wage with public works programs to mop up any incidental unemployment caused by a living wage. And the case for WPA-style public works programs for the long-term unemployed in today's near-Depression grows stronger by the day.

As long as the Straussian school consisted of a small group of uninfluential scholars who spoke mainly to one another, it could do little harm to the republic. But now that their attempt to rewrite American history in the service of contemporary conservatism is being broadcast to the world not only by demagogues like Glenn Beck but also by serious public intellectuals like George Will, the Straussians must be refuted. America does not need to choose between James Madison and Woodrow Wilson. But it does need to choose between Franklin Roosevelt and Herbert Hoover. And we know which side George Will, William Voegeli and the Straussians are on.

(Michael Lind is policy director of the Economic Growth Program at the New America Foundation and author of "Up From Conservatism: Why the Right is Wrong for America."

Shares