So it's true: Everyone looks for his or her first love on the Web. We all do it. Mostly because we can. Then time passes, we start to browse, check stock quotes and news, and we forget to keep looking. I did. I couldn't find him at first and, I admit, I did not diligently keep trying. So imagine my surprise when I checked an e-mail service that I rarely use, and there it was: a message from a screen name that I recognized instantly, sent to a screen name sufficiently different from my real one but, nevertheless, me.

Lo and behold, he had found me.

The message said, "I once knew an Eve Aisling Parnell -- and that's an odd name. She used to live in Rockaway. Did you?" I opened my member profile immediately and rued the visibility of E.A. Parnell, astonishing in its boldness. Why had I not created a sufficiently masking moniker, the way I had for my other e-mail accounts? Was I in trouble? Oh, was I in trouble.

"Replique me, my baby." He met me on the street corner and grinned. Replique was one of the fragrances I wore back then. And then there was Femme, by the House of Rochas -- who could forget that one? It sent him up the wall. We girls wore it, a veritable madam's parfum, only on weekend nights if we were lucky enough to score some -- it would never do for school days.

Before our first date, I left my friend Lauren's house on a Friday afternoon to meet him, wearing Estée Lauder Super Cologne -- it had just come on the market and her sister had a bottle. We rode the train to the East Village to see the movie "Che" about our idol Che Guevara and his girlfriend Tanya. Afterward, we went to his "apartment," a suitably decrepit place in a walk-up firetrap on Sixth Street east of First Avenue. He was 16, I was 15. Not many 16-year-olds had apartments in the village; it was quite a status symbol and a reliable girl catcher as well, but of course it did not last too long.

Once school began in September, there was no apartment anymore; during that school year and part of the next I was to take two buses to his house every evening after dinner. (I didn't have to sing "Magic Bus" -- even the bus knew it was magic.) The fact that we attended different high schools and lived miles from each other served only to underscore the preordained rightness of Andy and Evie as a couple.

Back then, you didn't date if you were hip -- you hung out. So we did. On the street to socialize, but mostly in his room. Talking, kissing, loving each other beyond life and death, we said. Hushed and humbled, we sprawled together listening to Graham Nash sing "Our bodies were a perfect fit, in afterglow we lay," subliminally aware that we were not the only tall, skinny boy and round, darker girl alive and in love. We celebrated anyway. Nearly every night we told each other, "This is one for the books," and meant it.

That is how we hung out most evenings, but not if there was a riot going on. If there was, we had to be there. We went to riots, peace marches, moratoriums, affinity groups, plenary sessions, you name it. We thrust our fists into the air and shouted, "Avenge Mark Clark! Avenge Fred Hampton!" after the Chicago cops broke into their house and killed two Black Panthers, one of whom I believe even now was sleeping when he was shot. And "Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh. NLF is gonna win!" Today I give myself 50-50 odds that I even knew what the initials NLF stood for at the time.

His parents were home in the evenings and entertained a great deal. They played Santana and the Moody Blues, which we scoffed at. The two of us disowned Santana shortly after he became too popular, but we liked to watch Andy's mother dance to "Black Magic Woman." I thought they played the album "Abbey Road" way too often, but hell! You were not about to walk into my parents' living room and hear "Abbey Road." Their guests, a blend of academics and brats in their 20s, would loll around and discuss music and politics, envying us, we believed strongly, because we were on the front lines of the revolution. We were the youngest ones in the room, at a time when youth was the most valuable currency going.

When Andy was covered with chickenpox I was allowed to visit because I had had the virus as a child. He looked just as beautiful that evening as at any other time. I brought him soda and told him not to scratch. His mother, Arlene, taught me how to cook the pasta called bucatini, and sometimes we played hearts or helped Andy's sister with her homework.

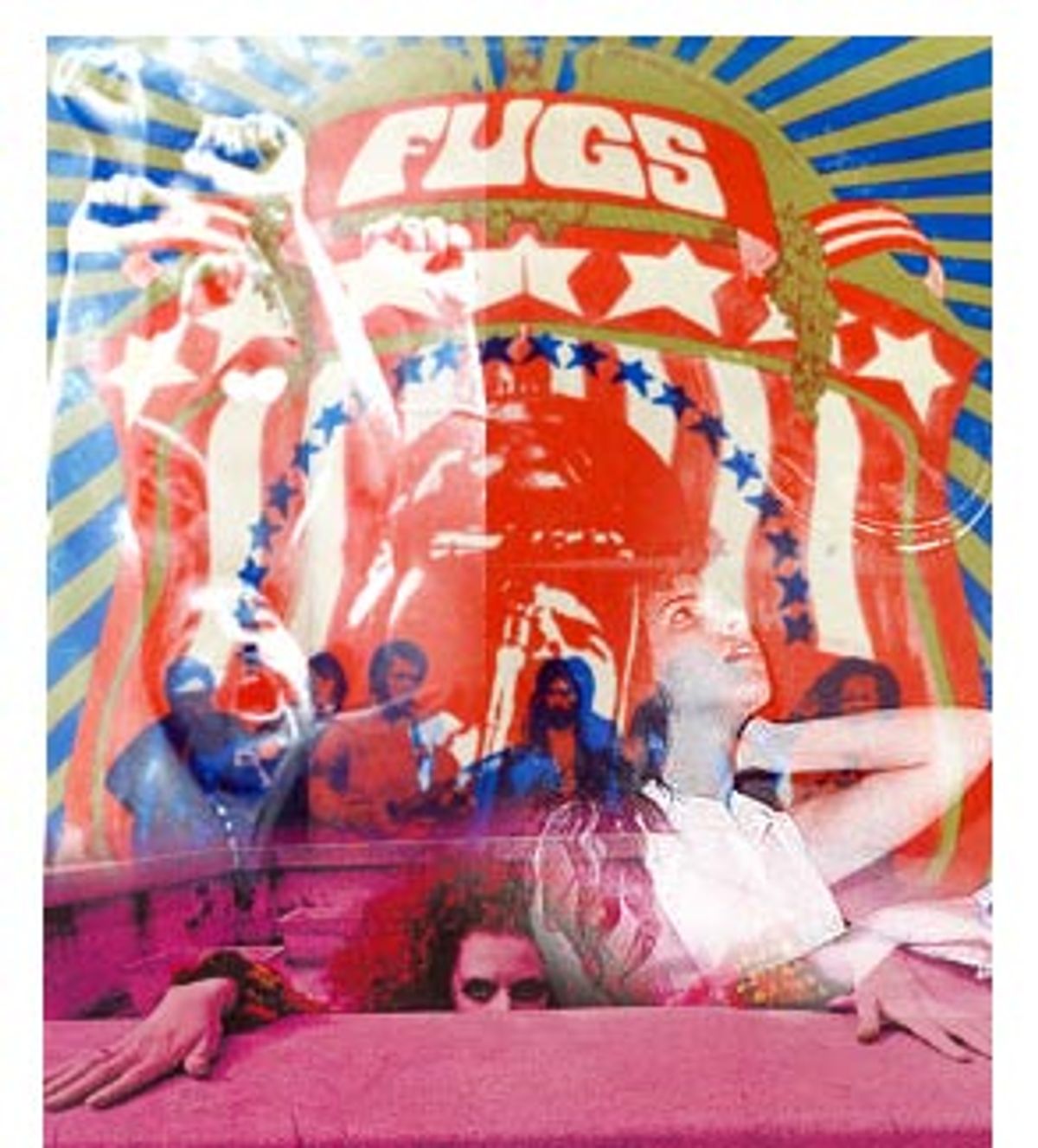

For Christmas, he gave me his old phonograph and his father gave him money to take me to the pancake house. He liked crullers but couldn't remember their name. I spent $9 to get him Frank Zappa's "Hot Rats" and two Fugs albums.

For at least a decade, I walked around thinking that I had stopped being a virgin on the night after the New York Mets won the World Series. I thought this when they won it again in 1986 and I was living it up in Isla de los Ladrones, by then a true Mets fan. I thought so for an awfully long time and was more devoted to the team for having played a part in my coming of age. But I was wrong -- it happened the night after they won the division: "The Mets won the playoff!" he yelled on Wednesday, and that Thursday night, we did it. When I came home I looked at my face in the mirror for ages to see how different, how womanly, I suddenly was. "Big girl," he said. "You're a big girl now." This occurred, of course, well before he began his numerical ranking system for the girls in his life or comparing the delights of our bodies in his notebook.

People say that the '60s were about sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll, but they weren't, not really. Drugs were just something to have around, like incense and ashtrays (except acid, of course, which any earnest teenager had to take far more seriously than homework). Radical politics got us going, assured us that we were an invincible tribe with absolute beatitude on our side. Sex was the vehicle in which we traveled. There was no credibility in virginity; it was as ridiculous as, say, liking the music of Chicago Transit Authority or Blood, Sweat and Tears without Al Kooper as frontman: shameful and lame-o. And love was the petrol. After I finished messing about with one of his friends and causing a crisis to rival "Anna Karenina," he wrote me a poem that ended, "Evie, I love you and I always will/The land lay flat before us/We've conquered the last hill." It wasn't his best work, but how profound for a 16-year-old boy, we agreed.

Thirty years ago, right now, I was carrying his baby. I wonder if he knows that. Is it something that he too would never forget? As he clicks the "Refresh" icon on his screen, checking his stock quotes and waiting for my response, does he remember how I snuck urine in a tightly closed jar, under a coat, from my house onto the subway train, all the way to the East Village free clinic? Or how he told me over the phone where to meet him? "Take the subway to DeKalb Avenue; I'll be at the front when you get off."

Does he remember how we plotted and schemed to get the paperwork done, and ate at a Blimpie near the hospital every time I had a doctor's appointment? The only way to do it was on "health of the mother" grounds. And the surest-fire way to present oneself as unhealthy as possible was to threaten suicide, which I managed rather convincingly. But I prefer to remember having lunch together, eating for that other I would never see and laughing at his jokes.

We had a good time before and after those hospital visits to see different psychiatrists for 10 minutes at a clip, and oh, did we love Manhattan, wide open and exciting -- spring in Spanish Harlem. Somehow, with minds honed at meetings of the high school student union, Andy and I plenary-sessioned until we had succeeded in hoodwinking both sets of parents into believing that I was going to Philadelphia for four days. When his father noticed that we were keeping the lights on in the bedroom more and more often, he said, "What's going on in there; are you two hatching an assassination plot?" We collapsed, smirking to ourselves, "If he only knew."

But keeping the lights on all those nights bore some pretty powerful results in strengthening us as a couple. We thought alike and we began to look alike, too: My oval face became more heart-shaped, and his hazel eyes grew browner. "Derrrrh Igg Fuhrrrr Mouhddh." If he remembers, then he and I are the only ones in the world who understand that phrase. We went to the office of some local doctor we had heard about. I thought he was mean and he refused to help me anyway, so when I ran out into the street I burst into tears. Andy made me laugh by scrambling every last part of the doctor's name into phonetic oatmeal.

He was a good boyfriend all during that time; I think it was only later that year, when the sister of that other girl died in a car accident, that he relegated me to second place. I was asked to "share" while he spent a weekend on grief counseling, and probably pretty tender sex, if you think about it. I could not refuse because I knew that sharing was right -- after all, the Jefferson Airplane's "Triad" was one of the songs we loved best: "I don't really see why can't we go on as three," sang Grace Slick, pleading to be with both lovely men at the same time. Not only did I play along, I believed it too. Not once did it occur to my malleable mind to say, "Hey, wait a minute! I thought you were my boyfriend."

We decided to avoid hysteria, but really we were too hip to become hysterical. The facts were plain. In those days, Irish girls had babies and Jewish girls did not. I was half each but it was simply out of the question. I had nothing against kids; I just did not want any of our parents to find out. "If we were older," we kept reassuring each other, we would live in the country and name the baby Sandoz after the Swiss pharmaceutical firm. So I had to procure a phony I.D. showing I was 18 years old, and by the time all these details were in place, months had passed and the only solution available was the saline drip, the procedure that most closely resembles a full-term delivery, the only difference being that you don't go through all that hassle for a live, healthy baby, but for a dead one. It was too late to do anything else. I was four months along.

The hospital admission and consultations were so exquisitely dramatic that I could have been onstage. I was brave and excited when a rat scurried across the floor of my room; distinctly middle-class, I had never seen one before but thought it was high time I did. I kept the phony hospital I.D. bracelet as a souvenir. But then, maybe after I was in there three days, the curtains went up for good and I had to quit thinking of myself as "Tanya in a hut."

We knew nothing about edemas, so when my hand swelled to six times its size from the intravenous needle, we panicked. The labor pains were so unexpected, their intensity so off the chart, that I sent Andy away because I could not bear the terror in his face. He was not with me when I delivered the little thing in the bedpan by myself. (I woke up from a pain shot and there it was. I no longer hurt. The bed did not have a call button, so I yelled for assistance and they came and took it away.)

Is he caught up now in the rapture of downloading MP3s, maybe drinking a beer?

I heard once that Andy had married well. Yet I had gone him one better, upholding our earliest prejudice against our natal country and marrying foreign. I was an expatriate carrying the same disdain for high school unity that we had shared as baby Weathermen -- we who had scorned our proms and graduation ceremonies. That was the last I ever heard of him, until a week ago.

I have now lived twice as long as the age I was when I first knew Andy and still I think of him in the purest terms, just as if these last two lifetimes had never been. He has tracked me down on the Internet, a staggering event. Through all the years since I last saw him, well before there was such a thing as the Internet, I simply figured that one day my secretary would buzz me on the good, old-fashioned interoffice communicator and say, "A Mr. Andy _______ to see you."

But no, he is on a screen before me in fonts I myself chose for their aesthetic appeal. He wants to know who and where I am.

What does one say after 30 years apart: "Where did you go to, my lovely?" or "Hello, it's me?" Do I tell him I am happily married with two kids? Tell him how grotesque I felt by the time I turned 18? Does this stranger prefer to hear that I have helped many people with AIDS or that I acquired the perfect tan? Which would matter more to him? "Yes, I live in Canada but winter offshore. I have an important meeting in Brussels next week, can't miss it, sure wish my sprained ankle would heal faster. And après-Bruxelles, well, Gerry Adams needs me." I can say anything at all. Design a life or reflect my real one.

Many times since he decreed that the other girl had won, I've thought that I'm not long for this world. Devoted parents, a decent education and street smarts gave me 30 extra years, but I didn't really need them. What for -- to make money? To bear two kids that Andy never knew? So I marveled at the beauty of Bali and the horror that is Bangladesh; I am not impressed, why should he be? I did most of what we said we would do -- back then. Definitely a hip old girl, but her gait is slightly shambling -- either a sprained ankle or the tardive dyskinesia of love. I didn't need all those years. You can have them back, Andy.

The abrupt end of my childhood is a little too sacrosanct to dally with, concomitant as it was, you might say, with the abrupt start of my womanhood. Which makes anything to do with him -- thinking, remembering, even, God help me, contact -- "heavy." So I will probably respond quietly. I will not tell anyone and then, late one night, I will send Andy a line from that most romantic of all morbidly romantic rock songs, "(Don't Fear) The Reaper": "The curtains flew and then he appeared."

See if he remembers. See what he does with that.

Shares