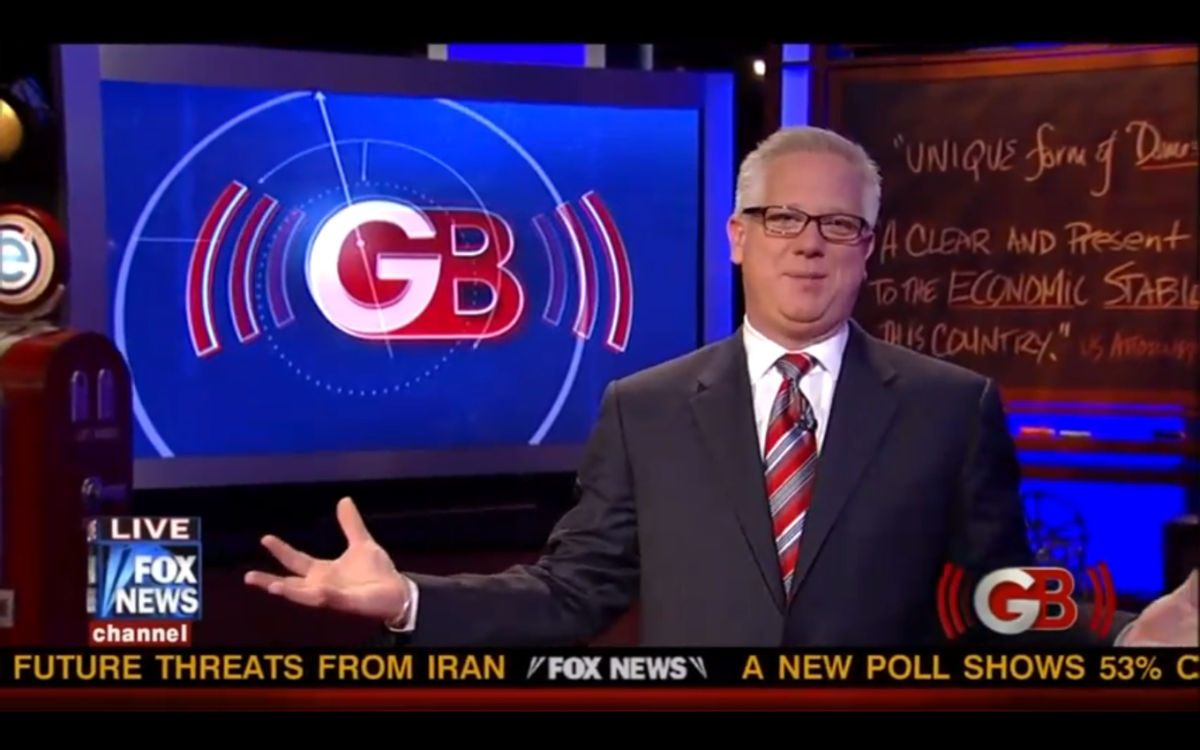

I try to ignore Glenn Beck as best I can. I really do. Yes, I know I wrote about his crazy caliphate ideas -- linking the godless American left with Muslim extremists in a plot to restore an Islamic caliphate that stretches from Cairo to Madison, Wis. -- as well as his vicious attacks on scholar Frances Fox Piven. After Beck-head Byron Williams drove to San Francisco planning to shoot up the obscure (before Beck crusaded against it) Tides Foundation, I think he's dangerous, but I also think he's a loon. Media Matters does a great job keeping track of his crusades, so if he foments violence again, we'll know about it. Generally I have better things to do with my time than parse Beck's latest nutty conspiracy theory.

But this week Beck is going after a former SEIU leader named Stephen Lerner, who presented an idea for direct action against banks to the LeftForum2011 conference last weekend. Tuesday Henry Blodget gave Beck's anti-Lerner jihad serious, worried attention in Business Insider -- Blodget quotes Lerner advocating "destabilizing the country," but in fact those words don't appear in Lerner's talk, though Blodget put them in quotes as if they did. I wound up following the links and reading what Lerner actually said. There's going to be a debate about Lerner's ideas, and there should be; some of them are excellent, some of them aren't so great. But his overall point is valid: Generations of protest, strikes and other kinds of nonviolent civil disobedience won us the economic and civil rights protections we think of as basic American values. (For that matter, the Boston Tea Party so revered by the right involved civil disobedience and property destruction.) We're not going to restore those rights without some of the same tactics.

By way of background, I noticed that Lerner once worked at the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, and I've been reading a lot about the ILGWU lately as I try to understand why the world is paying so much attention to the 100th anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire coming up Friday. For the record, I think the attention is a great thing; I am just trying to make sense of it, and I'll be writing more about it in a longer piece Friday. My short conclusion is the obvious one: The Wisconsin ferment showed that a lot of Americans are very worried about the power of the uber-rich over the economy. Clearly, the Triangle fire tragedy is seizing attention because it's a vivid, heartbreaking example of what happens when you have unbridled capitalism, no unions and a state dedicated to protecting the prerogatives of business owners, not the larger society. It's also getting attention because, in the words of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's heroic labor secretary Frances Perkins, the day of the awful fire was "the day the New Deal began." New Deal architects and New York powerhouses Al Smith and Robert Wagner led the remarkable four-year investigation into the fire, which resulted in an astonishing barrage of pro-labor legislation, creating new health and safety codes as well as restricting child labor and shortening the work week for women (to 54 hours).

But it must also be remembered that a lot of organizing and protest led to that post-Triangle labor agenda. In 1909, 20,000 garment workers, most of them women, engaged in a massive four-month strike, after Triangle workers voted to unionize -- and were promptly fired. Women who joined the "Uprising of the 20,000" regularly went to jail -- over 700 were arrested -- and in the end, the strike won public support and resulted in the unionization of several garment companies. But not Triangle. The awful tragedy just a year later proved the need for unions, and for state worker protection; without the union ferment and the four-month strike, New York politicians might not have paid the kind of attention to the Triangle tragedy that led to Smith and Wagner's legislative agenda and gave the rest of us the New Deal.

So: I don't endorse everything Lerner proposed, but I think he's right that change is going to require some kind of coordinated protest, and I applaud his ambition. The New Deal wasn't handed to us; it took decades of agitation, including strikes and civil disobedience, to get government and business attention. Progressives should be thinking about these strategies again, not just looking to the past but to the future to understand what coordinated action means in a post-union society, when even Democrats care more about Wall Street than Main Street.

I certainly endorse Lerner's analysis, particularly this: "What's changed in America is the economy doing well has nothing to do with the rest of us." It's alarming: The banks are doing well, the stock market is up, and yet unemployment remains at dangerous levels, the number of discouraged workers is at a long-time high – and no one in power seems to care. Our own Andrew Leonard, as well as Paul Krugman and Robert Reich, have written about this troubling disconnect repeatedly.

Lerner talks about a coordinated week of protests against banks, culminating in civil disobedience at a J.P. Morgan Chase annual shareholder meeting. He also advises students and homeowners who want to renegotiate high interest rates or unfair terms to simply stop paying their loans -- 10 percent of people whose mortgages are more than their equity are spontaneously doing just that, judging that delays in foreclosures might keep them in their homes longer while they figure out what to do. Lerner also suggest states and cities, prodded by public workers, should likewise negotiate with banks for lower interest rates, rather than laying off workers.

Using the leverage of students, homeowners, unions and governments to force banks to help those hurt by the fiscal crisis they caused -- now that the banks have been bailed out -- is a creative idea. Trying to "bring down the stock market" and create "a new financial crisis, for the banks, not for us," as Lerner advocates, seems risky and destructive. The destabilization Lerner sketches could have all kind of unintended political and economic consequences that hurt the people he cares about. And politically, it's a dead end: I don't think even people victimized by this economy are going to thrill to the rhetoric of destabilization and crisis; they want the economy to work more equitably, for all of us.

But the idea of civil disobedience to protest the banks' indifference to struggling homeowners, or the government's indifference to the economy's casualties, shouldn't scare anyone -- except its targets. It's perfectly American. We need to remember that the changes wrought by the civil rights movement, that are today hailed by Beck and even Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour, involved nonviolent civil disobedience. If the left-baiting of people like Beck deprives us of the tactics that won so many rights over the years, we're in big trouble. Beck lies so much it's not worth trying to correct him, but I did note that in his frothing about the Wisconsin union movement, he tried to argue that his alleged hero, Martin Luther King Jr., opposed collective bargaining for public employees. In fact, King died visiting Memphis to support the striking sanitation workers, the beginning of what could have been a new alliance between civil rights and labor rights that might have prevented the cultural meltdown that left the two movements alienated and at odds after King's death. King would likely give Stephen Lerner a respectful hearing if he were here today.

Henry Blodget, meanwhile, has a lot of gall to tsk-tsk over Lerner's ideas. The former stock analyst charged with securities fraud is himself a perfect symbol of corrupt Wall Street self-dealing. (He settled and was permanently barred from the securities industry and also paid a multimillion-dollar fine.) Hilariously, at the end of Blodget's alarmist piece, there's a link to a "related" Business Insider article: "15 Mind-Blowing Facts About Wealth And Inequality In America," which warns that we're living in a new "Gilded Age" -- which is, of course, what spawned the Progressive-era activism that included the Triangle Shirt Co. unionization drive, and the post-fire roster of reform.

If we're going to be terrified by proposals for nonviolent protest and civil disobedience that brought us the Progressive era and the New Deal, we're going to be living in a Gilded Age permanently. To call Lerner an "economic terrorist," as Beck does, is itself a kind of terrorism, trying to frighten Americans into disowning their own economic heritage and protecting the plutocracy that runs the country. Let's hope no Byron Williams-wannabe goes out looking for Stephen Lerner.

Shares