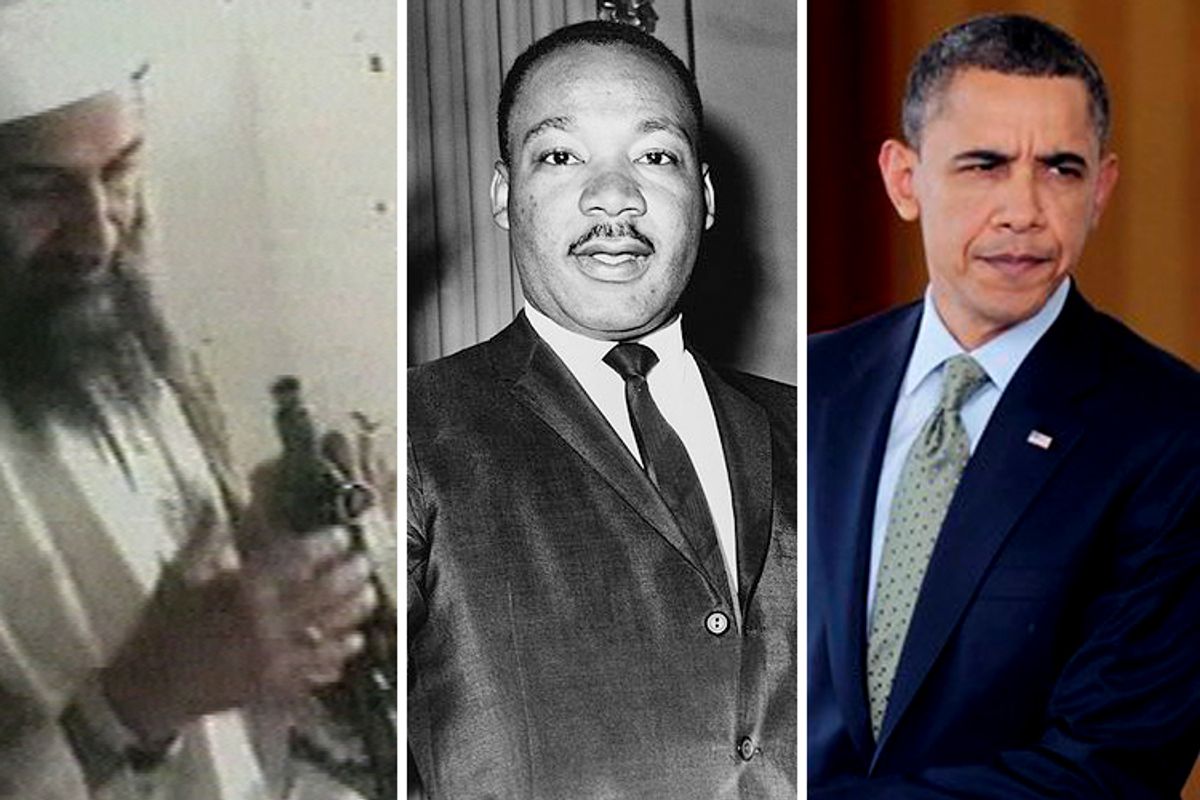

I've found myself fascinated by the controversy over the "fake" quote from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that went viral Monday, in the wake of the news about Osama bin Laden's killing. It's been the rage on Facebook and Twitter, broadcast to millions of social media users. It's already been debunked; and then the debunking was debunked. Beyond the messy details, I'm fascinated by the desire of all sides -- there aren't merely two sides to the debate over bin Laden's killing -- to claim King as their moral ally (or to at least make sure he's not on the other side!).

First, the messy details, quickly. Sometime Monday parts or all of the following "quote" flew around Twitter and Facebook, attributed to King:

I will mourn the loss of thousands of precious lives, but I will not rejoice in the death of one, not even an enemy. Returning hate for hate multiplies hate, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate, only love can do that.

Then someone Googled the first sentence, and found King never said it. The Atlantic's Megan McArdle went up with a "gotcha" post, accusing folks with reservations about both bin Laden's killing and its celebration with fabricating evidence that King would have agreed with them. But then it came out that, while King didn't say the first sentence, he had in fact made the other two statements, on Page 53 of his book "Strength to Love." And it turned out nobody "fabricated" anything: A 24-year-old teacher named Jessica Dovey wrote her own thoughts, sans quote marks, before the King quote, and posted it on Facebook, but as the post was cut and pasted and abbreviated in countless ways, King's words and Dovey's got jumbled. No fabrication; no harm, no foul.

But the frenzy over the King quote came along with a disturbing wave of thought-policing, from all over the political spectrum, and they seem to be related. Battles raged Monday not so much over whether the U.S. killing Osama was morally or legally justified, but over the right way to feel about it, and the right way to express those feelings (which seemed to be the core issue the King "quote" was addressing). Has social media made us a nation of biddies, chiding everyone over the "appropriate" way to feel about public events? David Sirota's Salon piece, "'USA! USA!' is the wrong response," was widely attacked. Maybe I should count Sirota among the feelings-police, but he made a valid political argument, and he came in for an avalanche of criticism merely for suggesting sobriety, not celebration, was the right response to bin Laden's death. It was somehow read as Sirota criticizing Obama's decision, which he did not. (It was also posted more than 100,000 times on Facebook, so a lot of people also agreed with Sirota.) Can one both believe that the killing was the right thing to do, and also be sober, even sad about it? Yes, you can, but in some quarters, anything less than high-fiving the president's "victory" was suspect.

I witnessed a similar Facebook and Twitter frenzy last week when President Obama released his long-form birth certificate. I wrote on Twitter, Facebook and my blog that I was "sad" the idiotic birther controversy had come to that. Within moments tweets were flying -- I'm beginning to conflate Twitter with Angry Birds, given all my Twitter trouble lately -- accusing me of finding fault with Obama's decision to release the long-form document. I expressly wrestled with the good-or-bad move question in my blog post; and I came down ambivalent. But I was not ambivalent about my sadness the president had been forced to prove his legitimacy to the likes of Donald Trump. People can feel otherwise, but why attack me for a heartfelt response to an insult to the president?

As I wrote on Sunday night, I personally had a hard time seeing bin Laden's death as something to celebrate, but I didn't judge those who did. The 9/11 attacks were of such enormity, rippling out to reach so many people in such different ways, we're all entitled to our subjective reactions; it was everyone's tragedy, and everyone grieves differently. Ultimately, I'm with Mona Eltahawy, in feeling like I could have done without the drunken "frat-boy" air of some of the partying; but for all I know, someone I see as a drunken frat boy might have lost his mother in the towers, or on one of the doomed planes.

I think we're seeing the rise of the Feeling Police because in a time of profound social dislocation, a lot of people aren't sure what they believe about right or wrong, justice or injustice, and they're not sure whom they trust to give them information and guidance about it. It might be the New York Times; it might also be some witty guy on Twitter; it might be Penn Jillette on Facebook; at its best it's a moral and political figure like Martin Luther King Jr.

But we can't outsource our own moral or political values to Dr. King. We also can't ask President Obama to be Dr. King. I realized years ago that was part of my own problem with Obama being a mere mortal politician, making compromises whether on healthcare reform or government spying. He's a gifted politician who seems to have a strong moral core, but he's a politician; and now he's commander in chief. I can't expect him to be the prophetic, perfect visionary we white liberals have needed our black leaders to be. Also: You can believe fervently in the power of King's words about love, and hate, and violence -- as I do -- and still accept that President Obama did the right thing, based on the knowledge he had before him.

And for now, I do. That doesn't mean I won't avidly consume every new account of the operation that led to bin Laden's killing. If some of the information behind it was acquired through torture or other "extra-legal" means, I want to know that. I may come to believe the president made the wrong decision, but I don't think that, given what I know.

Back to feelings for a bit: We can't help focusing on feelings, in the absence of hard information. We're social animals; we trust our "feelings" to tell us something real. So I had very intense feelings looking at the now iconic picture White House photographer Pete Souza snapped of the president and his team as they "watched" the bin Laden operation in the Situation Room Sunday night. (There's no hard information about what they were actually watching.) You've seen it. It's riveting. Hillary Clinton is beyond anguished; her hand is over her mouth, her eyes red-rimmed. The only person looking as grim is the president himself; he's slumped in his chair, looking hard at the screen. Vice President Joe Biden looked stricken; the New York Times reported that he was fingering rosary beads. The military leaders in the room were more granite-faced, but I was reassured to see our civilian leaders grimacing at the reality of killing bin Laden and his family members – even if they'd make the same decision tomorrow. Their "feelings" -- at least what appear to be their feelings -- reassure me they approached the decision with the moral gravity it deserved.

If Hillary Clinton had been pumping her fist and yelling "USA, USA!" after the killing I'd have been aghast, and said so. The range of "appropriate" feelings -- and the way you telegraph them -- is more clear-cut when you're talking about our leaders. Being reassured by seeing their feelings, while we wait for information, makes sense. But ultimately we need, as citizens, to decide if we believe this was a just decision, a moral decision and a decision that made the U.S. safer (which may add up to three different things.) We can't simply outsource that judgment, whether to King, Obama or our favorite pundits. Wasting time adjudicating whether people are expressing the right reaction in the right way is a silly distraction.

Shares