The advice is pretty much exactly what you'd expect from a loyal Democrat to wavering House members of her party, unsure whether to vote for a healthcare reform bill or not: Stop dithering, and just do it.

"There's a difference between leading and being led... I think you have to decide what is fundamentally right, and not listen to those people who are such extreme naysayers."

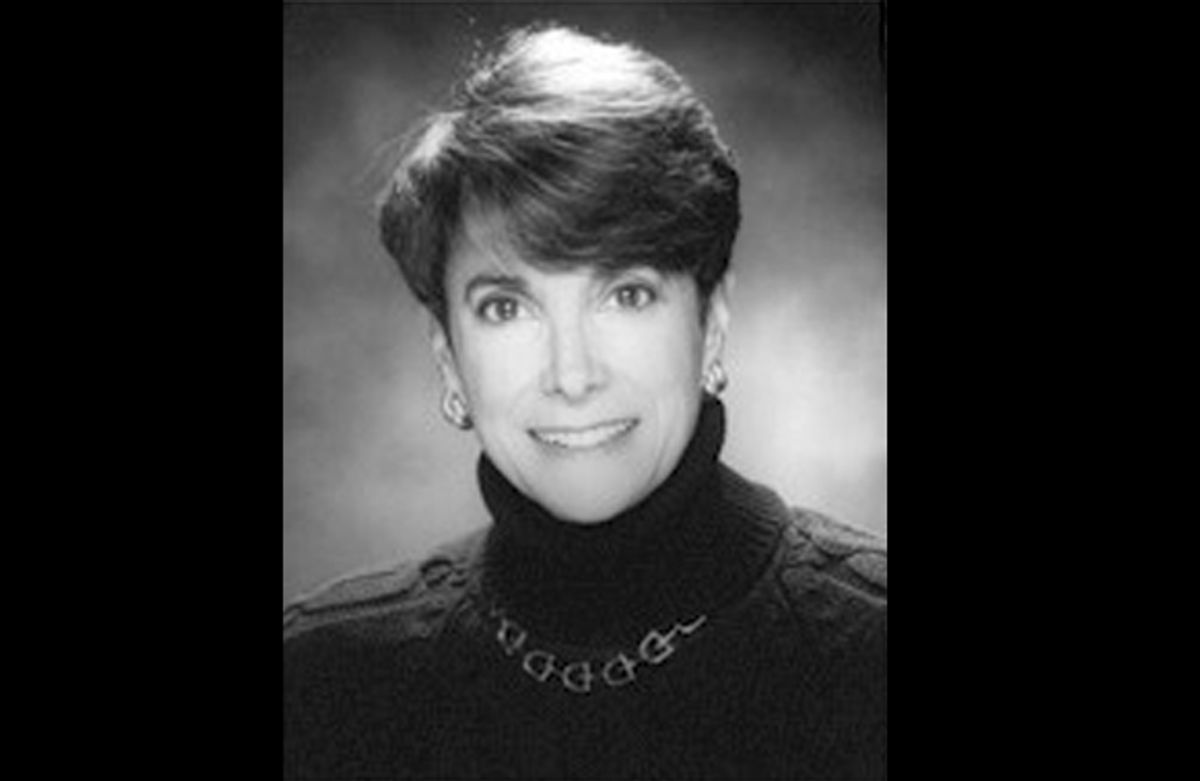

But the source of it might give it a little extra weight with any Democratic lawmakers anxious about becoming the 217th vote for President Obama's healthcare bill in the face of ferocious Republican attacks: Marjorie Margolies, the former House member from Pennsylvania who was pilloried, and eventually lost her seat, for providing the one-vote winning margin for Bill Clinton's 1993 tax-raising budget. (She was Marjorie Margolies-Mezvinsky then.) When she says sometimes tough votes are worth casting anyway, she knows what she's talking about.

Margolies had been elected in 1992, winning an open seat in a district Republicans had long held on the strength of Clinton's presidential coattails. Which only makes the similarities to this year, and the 21 new Democrats in Congress, even sharper. The debate over Clinton's budget was bitterly divided; the administration, and Democratic leaders, called it vital to helping the government recover from a recession, but Republicans recognized that raising taxes (even on the wealthy) was politically toxic, and refused to vote for it. When Margolies cast the deciding vote, she recalls seeing a nearby Pennsylvania Republican jump up and down, waving, "Bye-bye, Marjorie."

Still, she told Salon this week that Democrats in Congress now need to get past narrow concerns about their own political survival, and vote for the healthcare bill if they believe, as she does, that it's necessary.

"It's the fundamental fear that people who are members have of losing their seats," she said. "And you can't blame them -- it's so darn hard to get there."

Margolies could justify her vote after the fact to voters -- but not in the language of 30-second attack ads. "The problem for me was that I could explain to a group in a fairly coherent, cogent manner what it was all about," she said. "And it made sense. It was 4 minutes long, though."

These days, 17 years after her fateful vote, Margolies teaches at the University of Pennsylvania's Fels Institute of Government and runs Women's Campaign International, a nonpartisan, non-profit group that helps prepare and advocate for women politicians around the world.

If passing healthcare is important, she said, Democrats just have to swallow hard and do it. Even if it means early retirement.

"People have to really step up and say, 'This is it,'" she said.

Shares