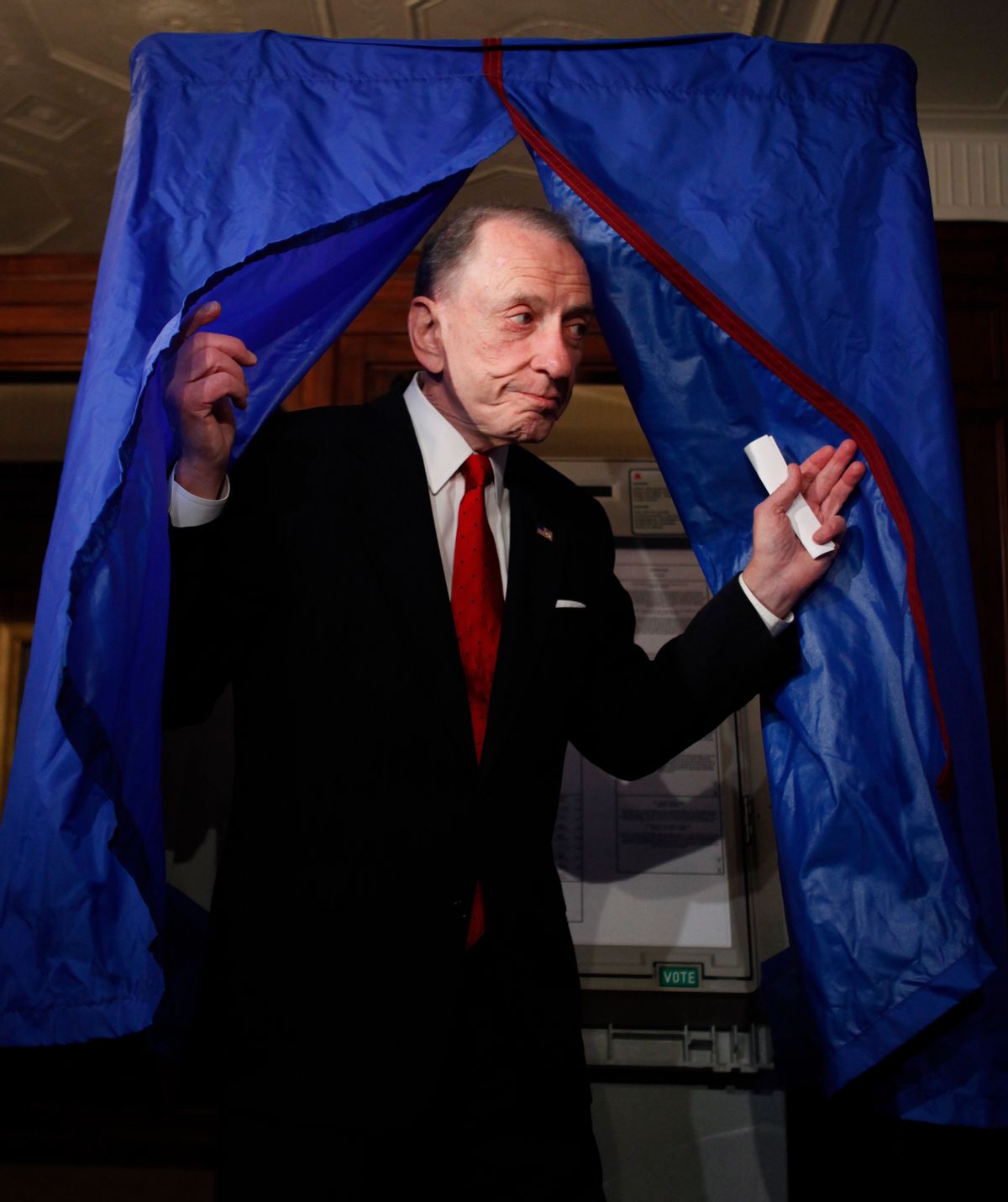

The Arlen Specter era ended with more of a whimper than a bang Tuesday night.

In a race few voters bothered to show up for, Rep. Joe Sestak ended Specter's political career after 30 years in the Senate, defeating him easily -- the AP declared Sestak the victor less than three hours after the polls closed -- to win the Democratic nomination for the seat Specter held. He'll face Republican Pat Toomey, who drove Specter from the GOP primary last year, in the fall.

A few minutes after the news broke, Specter strode into a half-empty ballroom in a Center City hotel and said a quick goodbye. "It's been a great privilege to serve the people of Pennsylvania," he said. "And it's been a great privilege to be in the United States Senate. I'll be working very, very hard for the people of the commonwealth in the coming months. Thank you all." And then he strode off the stage, his eyes rimmed in red, accompanied by his wife, Joan, his son Shanin and his granddaughters. And an already mopey party turned downright pathetic. (The DJ said he'd been told to play upbeat music, but avoided anything too celebratory "in case he don't win.")

Philadelphia, which Specter had been counting on to deliver the race, struggled to serve up more than 150,000 votes -- which in some years past had been the margin that candidates from the city won its precincts by. Sestak blew Specter away in rural counties and beat him easily near Pittsburgh. The Philly suburbs, some of which Sestak has represented in the House since 2006, went for him heavily.

Specter had been well ahead in polls until a few weeks ago, when Sestak -- whom people around the state hardly knew before then -- suddenly surged. The biggest lesson of the night seemed to be that Democratic voters want to vote for, well, Democrats. Specter lined up powerful endorsements when he abandoned the GOP, but none of them -- the White House, the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (which paid for some of Specter's TV ads in the closing weeks), Gov. Ed Rendell, the city Democratic machine -- managed to get the party faithful to get behind him.

Rendell tried to put a happy spin on the news, though he'd been outspoken in saying that Specter would be a better candidate than Sestak for the general election. "Look, we have 1.3 million more Democrats in Pennsylvania than Republicans," he said. "We gotta give them a reason to get out and vote this fall, and if we do, Joe will win." He offered an elegy for Specter, who he said had always delivered for the city and the state: "No one served longer than Arlen Specter, and no one served better ... No one's done more for the state than Arlen Specter."

Speaking to his supporters in Valley Forge, Pa., Sestak tried to set himself up as an outsider, calling the victory "a win for the people over the establishment, over the status quo, even over Washington, D.C."

For years, Specter had seemed more or less invincible. Democrats didn't even bother running serious candidates against him in some elections, a nod to his ability to win crossover votes. Six years ago, Joe Hoeffel fell short even as John Kerry won the state in the presidential election. Switching parties, though, seemed to finally do to Specter what no one else had been able to. Sestak hounded him for insufficient commitment to Democratic values, and then hit him with a devastatingly effective ad that made the switch look opportunistic and insincere. (It was certainly opportunistic; Specter had cast enough votes with Democrats over the years that it probably wasn't entirely insincere.)

Specter's career in public life spanned decades. He started out as a Democrat, then switched to the GOP in 1965 when he was elected district attorney. He worked on the Warren Commission investigating John F. Kennedy's assassination -- coming up with the "single bullet theory" that has infuriated conspiracy theorists ever since -- and after a few failed attempts, made it to the Senate in the 1980 election. There, he became a frequent thorn in the side of GOP leaders, opposing Robert Bork's nomination to the Supreme Court and voting for abortion rights. But he also hounded Anita Hill during Clarence Thomas' Supreme Court hearings, which some Democrats brought up during this year's campaign. In 1998, he voted "not proven" on the question of Bill Clinton's impeachment -- citing Scottish law as a precedent. Over the years, he hung on even though he infuriated people, proving that being an effective, but surly, lawmaker can work.

Beating Toomey now may take more out of Sestak than beating Specter did. It's a good year for Republicans, and Sestak may struggle to win over the kind of moderate Republicans or independents who routinely voted for Specter in previous elections. The biggest challenge could be getting Democrats to show up at all in November -- with 86 percent of the vote in Tuesday night, fewer than 900,000 ballots had been cast in the primary. Republicans, who had no real contest on their side, still turned out more than 600,000 people.

But the Democratic victory in a special election in western Pennsylvania -- in a district John McCain had carried in the 2008 presidential race, even as President Obama won the state by 10 points -- may give the party some hope. They hammered the GOP candidate, Tim Burns, for his business ties. Toomey, who spent a career in Washington battling for lower taxes on corporations, offers a chance at being the same kind of target. They'll just have to do it without Specter. Who -- until Tuesday -- had seemed like the ultimate survivor.

Shares