Somehow I missed this yesterday, but the Washington Post's Richard Cohen authored a truly absurd column that purported to explore a mystery that isn't actually a mystery: Why Barack Obama is not getting credit ("credit," being defined as strong job approval numbers) for the significant achievements that have marked his first 18 months in office.

The reality, of course, is that his approval rating is exactly where it should be for a president facing unemployment near 10 percent. Legislative triumphs like those Obama has enjoyed, no matter how important from a policy standpoint, will never lift a president's poll numbers if the economy is in the gutter. If Obama were now sitting on a 60 percent approval rating despite the economy, it would be a mystery. But he's not.

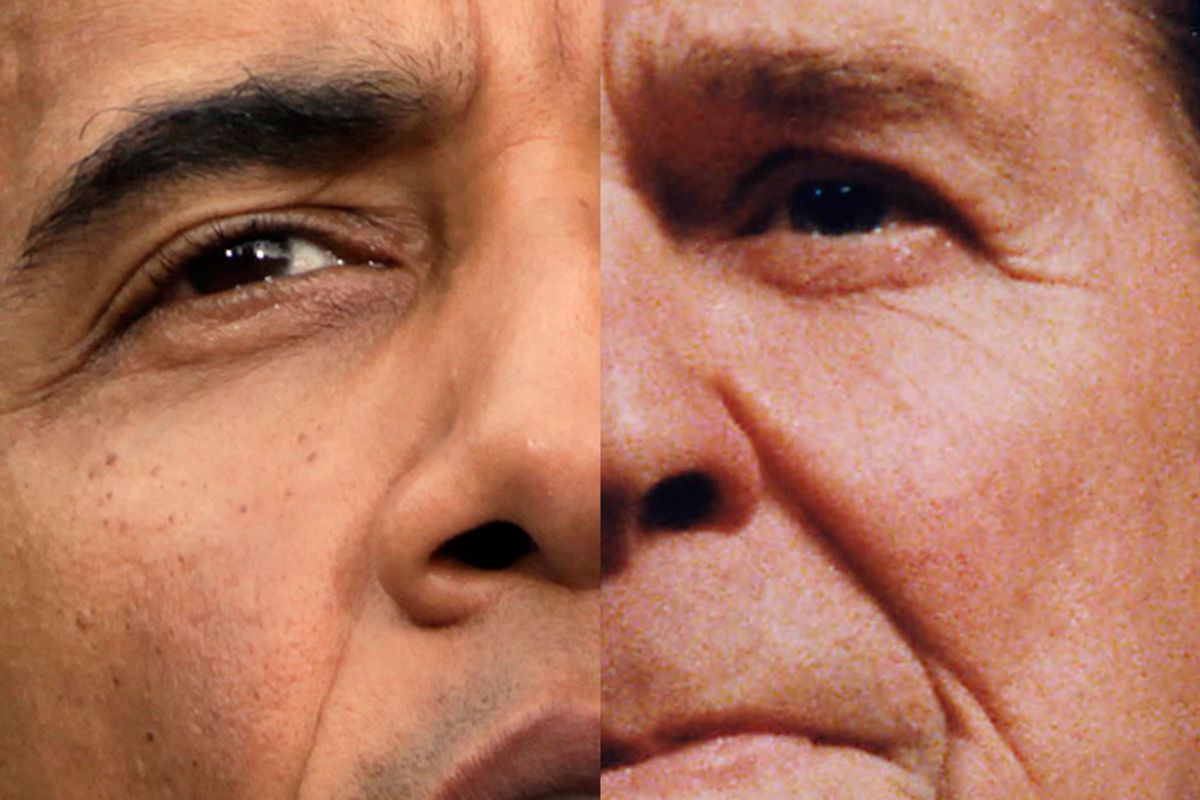

Nonetheless, Cohen plows ahead, claiming he's discovered the real reason for Obama's entirely unremarkable polling plight: "Before Americans can give him credit for what he's done, they have to know who he is. We're waiting." To support this conclusion, he draws a completely false distinction between Obama and Ronald Reagan, whose first two years in office were marked by nearly identical economic and polling turbulence:

The comparison to Reagan may give Obama cheer, but it is not really apt. For even in Reagan's darkest days when, according to Gallup, six out of 10 Americans reported that they did not like the job he was doing, an astounding six in 10 nevertheless said they liked the man himself. He was, of course, phenomenally charming, authentic and schooled at countless soundstages in appearing that way. Just as important, the public had faith in the consistency of his principles, agree or not. This was the Reagan Paradox and it helped lift his presidency.

I really don't know where to begin with this.

First, Obama actually is pretty popular at a personal level, and his favorable numbers outpace his job approval numbers. It's true that Reagan's personal favorable score hovered around 60 percent at this point in his presidency, but let's put that in some context. In October 1982, just a few weeks before his party suffered deep losses in the midterm elections, Ronald Reagan's job approval rating stood at 42-48 percent in a Gallup poll. In the same poll, his personal favorable number was 60 percent -- but with a catch. Here's how the New York Times reported it:

The Gallup organization also noted that Mr. Reagan's personal popularity is lower than comparable ratings for other recent Presidents at similar points in their terms...In April 1980, for example, when only 40 percent of Americans approved of President Carter's job performance, 66 percent gave him a favorable rating on his personal appeal

So for all of Cohen's talk about Reagan's charm and Irish jokes, his favorable numbers in 1982 were actually most notable for how low they were -- lower even than Jimmy Carter's numbers were at one of the bottom points of his presidency. Yes, Obama's numbers are lower today, but I'd suggest that's mainly a consequence of the 24-hour news cycle, which was just beginning in '82.

But that's a relatively minor point. The main flaw with Cohen's column is that he's writing about 1982 from the vantage point of 2010. He knows how the story turned out: the economy roared back in 1983 and 1984 and Reagan was reelected in one of the most thorough landslides in American history. And he's using that knowledge to gloss over (ignore, really) how serious Reagan's political problems really were in '82 -- and how utterly worthless his vaunted charm and communication skills (which Cohen spends paragraphs celebrating) were in alleviating them.

Consider some of the findings of a poll conducted by Cohen's own paper three weeks before the '82 vote (when the unemployment rate stood at just over 10 percent):

* "By an almost 2-to-1 majority, 61 percent to 33 percent, the public rejects the recent assertion by Reagan that "people are better off today" than when he took office in January, 1981."

* "Fifty-seven percent of those interviewed said 'things in this country have gotten pretty seriously off on the wrong track;" only 35 percent feel things' are generally going in the right direction" -- a measure that White House political strategists themselves say is a vital one."

* "Sixty percent of those interviewed said they disapprove of the way Reagan is dealing with 'the financial problems of the Social Security system;' 26 percent say they approve."

* "Sixty-nine percent said the Reagan Administration should do more to help the poor. Only 23 percent said the Administration is doing enough or too much to benefit the poor."

Mind you, Reagan was also able to point to some remarkable legislative feats. His 1980 landslide had delivered a Republican Senate and a working conservative majority in the House. The tax cut package he pushed through in the summer of 1981 was nothing short of sweeping. And he touted it relentlessly, even as the jobless rate edged higher and higher, promising Americans that it would eventually pay off and reminding them that the unemployment rate can be a lagging indicator of recovery. But -- and this absolutely can not be emphasized enough -- IT DID NOT MATTER.

Voters tuned him out and -- by wide margins -- concluded that his polices had failed. Polls in '82 and early '83 showed all of the likely Democratic candidates for the '84 presidential race beating Reagan. Reagan's own party began abandoning him, too. After the '82 elections, GOP leaders on Capitol Hill talked about working with Democrats to pass stimulus legislation over the White House's objections. Liberal Republican Sen. Bob Packwood trekked to New Hampshire, teasing the possibility of a primary challenge from Reagan's left in '84. Not that conservatives were happy with the Gipper, mind you: They openly called him a sellout for not aggressively pursuing their social agenda and for listening too much to Jim Baker, his pragmatic chief of staff. Among Republicans at the end of '82, the consensus was that Reagan wouldn't -- and shouldn't -- seek a second term in '84, and there were even rumblings of a primary challenge from the right. Jack Kemp, Jesse Helms and William Armstrong were all mentioned by conservative activists.

Cohen would have you believe that none of this ever happened -- that even as joblessness soared, even as his party suffered an awful midterm, even as his poll numbers collapsed, even as members of his own party gave up on him, even as polls showed a widespread lack of confidence in his leadership and his policies, that even after all of this, Reagan was somehow insulated by his charm and his convictions.

This may make for a nice narrative in 2010, but it's absolutely bogus. Reagan's turnaround began when the economy finally showed signs of life and the unemployment rate began falling. From a high near 11 percent in 1983, it had fallen to under 8 percent by Election Day 1984. At that point, voters were happy to reward him and happy to celebrate his charm and good humor. But rest assured, we'd be telling a much different story of his presidency if the unemployment rate hadn't dropped.

Shares