Ben Smith has a helpful post documenting the likely 2012 GOP contenders' public statements on the "ground zero mosque." Not surprisingly, none of them are for it. What is surprising, though, is how long it took Mitt Romney to express his opposition.

It was, after all, more than three weeks ago that Sarah Palin called on "peace-seeking Muslims" to "refudiate" the planned community center -- a pronouncement that spurred Newt Gingrich to declare that the Cordoba House shouldn't be built until churches are constructed in Saudi Arabia. Others have followed suit, and the political incentive is obvious: As I wrote on Sunday, Islamophobia binds the GOP's voters together today like anti-communism did a generation or two ago. The mosque is an easy red meat issue for any Republican thinking ahead to Iowa and South Carolina.

And yet, Mitt has been AWOL from the pile-on. We asked his spokesman for a comment more than a week ago, and never heard back. Smith, apparently, had a similar experience. Only after his piece went up this morning did Eric Fehrnstrom, Romney's press guy, say that his boss opposes the mosque because of "the wishes of the families of the deceased and the potential for extremists to use the mosque for global recruiting and propaganda."

At first glance, it seems like Team Romney may have been caught sleeping. But I doubt that's what's going on. Romney has been pursuing the presidency with single-minded determination since 2004, when he began junking the moderate image he'd used to win election as Massachusetts' governor in 2002 and rebranding himself as a fire-breathing conservative.

Back then, Mitt had a lot of compensating to do. He'd left an extensive paper (and video) trail of cultural liberalism (and a boast that he'd voted for a Democrat for president) in the Bay State. So his strategy was simple: get as far to to the right as possible and do it as quickly and loudly as possible on every issue that resonates with the national GOP electorate -- abortion, gay rights, immigration and so on. Past positions be damned. If doing so threatened to make him a tougher general election sell -- well, he'd deal with that when he got there. And he'd never get there if he couldn't overcome the skepticism of the GOP's very conservative base. This was the Mitt who, for instance, called for the wiretapping of mosques in 2005.

It worked well enough in 2008. Romney won a lot of admirers, briefly emerged as the GOP front-runner, then finished in second place. Which was fine with him: By February '08, when he dropped out, it was clear that the fall campaign would be a very heavy lift for any GOP nominee. So finishing second in the primaries and establishing himself as the next-in-line candidate for '12 wasn't a bad consolation prize.

And now, as '12 approaches, the challenge is a little different for Mitt. His Massachusetts past is more distant. There's still skepticism on the right about his commitment to the cause (and there always will be), but it's not as intense. He has, in other words, just a little more wiggle room -- more of an opening to balance general election calculations with GOP primary imperatives.

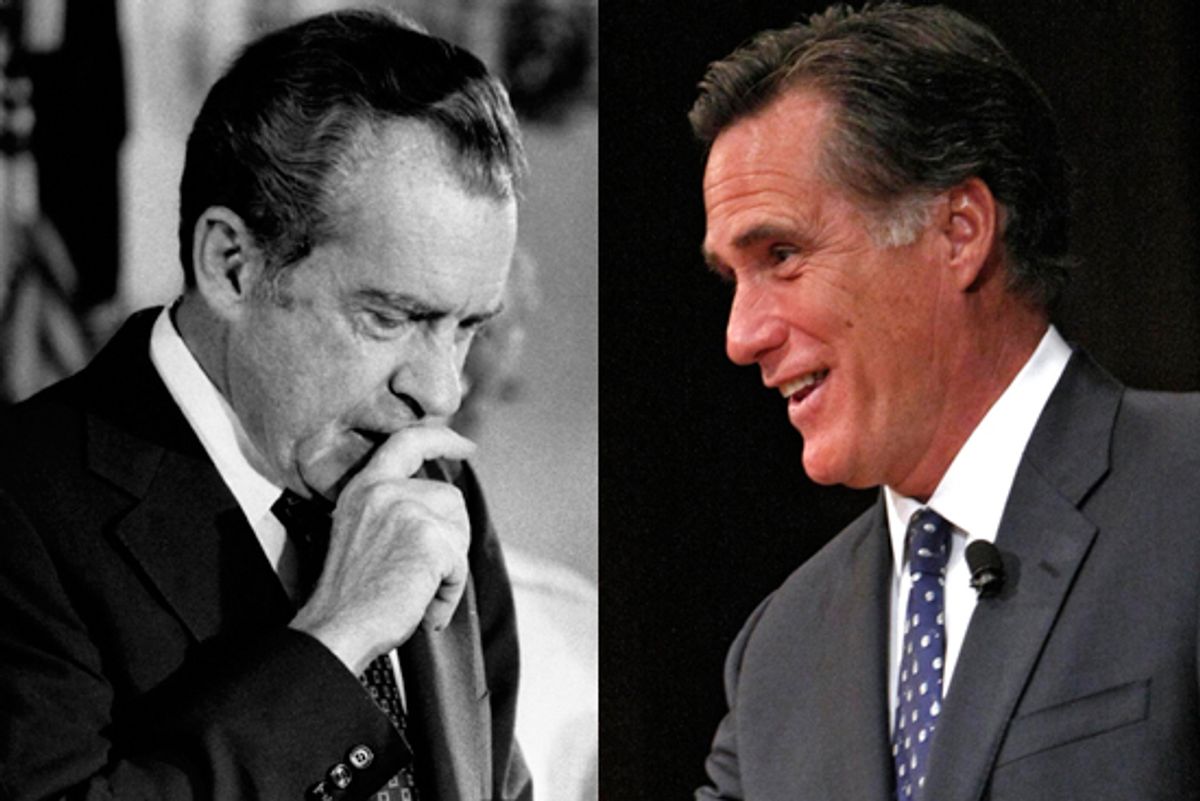

Here, a parallel can be drawn to Richard Nixon, like Mitt an ideological chameleon with an overpowering drive to claim the White House. Back in 1966, when a midterm election with eerily similar dynamics to this year's, was playing out, Nixon was furiously positioning himself for the '68 presidential race. With riots breaking out in cities and Vietnam protests growing in size and volume, the major issue, by far, was "law and order." With little subtlety, GOP candidates were playing on white America's racial fears and resentments, peeling off the white ethnic base of the Democratic Party. It was a political gold mine -- the GOP ended up picking up 47 House seats. But, as Rick Perlstein points out in "Nixonland," Nixon -- who kept up a frantic schedule campaigning with GOP candidates all year -- tried hard to avoid talking about "the hottest Republican issue":

It served a political requirement. What Richard Nixon was campaigning for now was respectability. Yes, law and order was breaking down; the crime rate was making ordinary Americans terrified to walk the streets; "the cities" were becoming wastelands. But others were doing just fine tying these facts to Lyndon Johnson, softening him up for 1968: George Wallace, Ronald Reagan, dozens of lesser figures. There was no percentage for Nixon in adding to the pile-on. The task now was making sure the pundits and the papers no longer considered the idea of him competing for the presidency as a joke. The key to that was raising his stature.

I'd chalk up Mitt's mosque reluctance to the same basic calculation. Sure, he's staked out his share of embarrassing red-meat positions this year; he only has so much wiggle room, after all. But where's the percentage for him in the mosque issue? The Mitt of 2006 and 2007 would have been all over it, but in 2010, he has a little less to prove to the right. Which made staying out of the fight a chance for Romney to gain a subtle stature advantage over the rest of the field. Of course, once the media started asking questions about his silence, he had no choice but to dive in, lest the GOP's Islamophobic base think he was going soft on Muslims. But I'd say Mitt's silence these past few weeks was quite intentional.

Shares