Since announcing Saturday's "Restoring Honor" rally, Glenn Beck has steadfastly maintained that it's not a political rally.

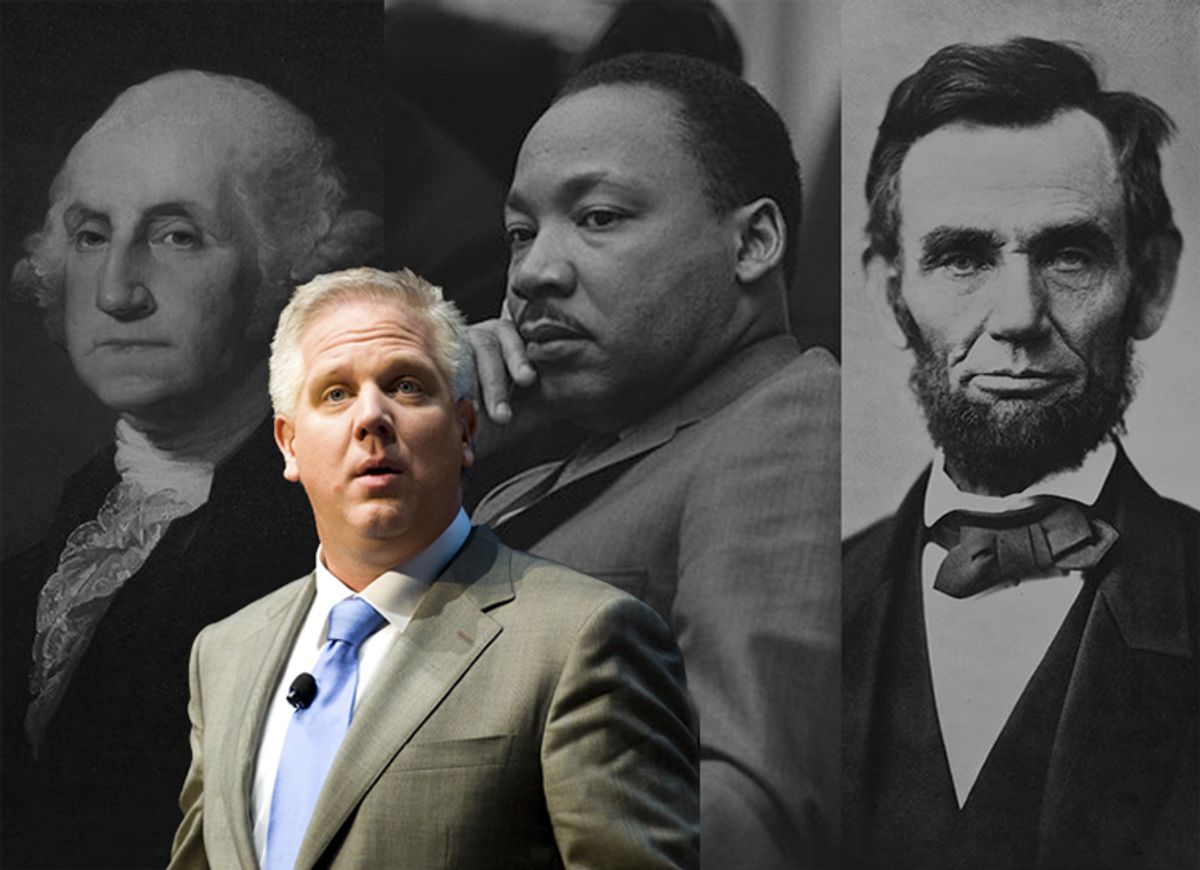

In the promotional video "We Need Heroes," he claims, "This has nothing to do with politics. It has everything to do with -- who are we?" He venerates "our sacred American heroes and ideas" and proclaims that "we need a George Washington, or a Thomas Jefferson, or a Ben Franklin." Images of Jefferson, Franklin, Washington, Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King provide a backdrop to a single word: honor.

Beck claims to be restoring not only honor, but truth: to be setting the record straight on liberal revisionist history. But his history is the most revisionist of all.

By invoking great American leaders in a call for apolitical heroism, Beck seeks to whitewash the political struggles and debates of earlier eras: to suggest that our finest leaders have always been above politics, and that to achieve their greatness, we need to rise above politics and do "the right thing."

It's certainly true that Franklin, Jefferson, Washington, Lincoln, King were great orators, philosophers, writers and leaders. But they were also great politicians, and to pretend otherwise is to disown the most enduring legacy of American history: that political expression, action and leadership are essential to the health of our democracy.

Benjamin Franklin was not only an eccentric, bespectacled paragon of virtue and wit, but also an active politician whose career included a stint as a speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly during which he fought the Penn family for control of the then-colony.

Thomas Jefferson was not only an eloquent writer and great philosopher, but also an ambitious political schemer. During his time as Washington’s secretary of state, Jefferson fought bitterly with Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton over fiscal policy and political philosophy, even seeking, unsuccessfully, to remove Hamilton from office through accusations of corruption and ineptitude. Hamilton’s Federalist Papers, now part of the core curriculum of high school American history classes, were essentially political propaganda, the product of the fierce battles waged between Jefferson and Hamilton in the newspapers and pamphlets that constituted the chief media outlets of the day.

George Washington, however revered, was unable to bring about peace in his Cabinet, and privately worried: "I do not see how the Reins of Government are to be managed, or how the Union of the States can be much longer preserved." Washington, who disliked political parties and political maneuvering, is the only one of Beck’s heroes to whom the term "apolitical" can even remotely be applied. But still, he sided with Hamilton more often than not and feared Jefferson’s rise to power after his resignation.

Abraham Lincoln was politically ambitious, and agonized over his political defeats. He was a product of the party system and an important figure in the Whig Party first, and then the Republican Party. Lincoln used his legendary debating skills to make brilliant -- and political -- arguments against slavery and the dissolution of the Union. But his position on slavery evolved gradually in response to shifting political conditions: He initially opposed only the extension of slavery to new Western states, and only endorsed emancipation outright once he believed it necessary for the restoration of the Union.

If anything, some of the strategies used by Beck’s heroes are more troublesome than those utilized today. We would not, for example, look favorably on a politician who purchased a supportive newspaper, as Lincoln did in 1859, nor condone the appointment of sympathetic journalists to Cabinet positions, a tactic that Jefferson utilized in his struggles against Hamilton.

Finally, King, though never a candidate for office, was one of the great political organizers of American history. His legacy has largely been whitewashed since his death; he has been stripped of any hint of radicalism, controversy or political savvy to be hailed as a saintlike figure. His "I Have a Dream" speech has likewise been distilled in the public consciousness to the most nonthreatening, apolitical aspects -- images of white and black children joining hands in the spirit of brotherhood, of multicolored harmony. But previous lines speak of voting and economic mobility, of police brutality and the "marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community," of jail cells and slums. It is a politically challenging address, just as King was a politically challenging thinker and leader.

Conversely, Beck's is a sanitized, easy-to-swallow vision of political change: some people -- the Lincolns and Jeffersons of the world -- are simply right. (Never mind that some of Beck’s heroes hold conflicting beliefs.) They are heroes, and they keep us from going astray by the sheer strength of their vision and honor. It is also a deeply misleading one, one that neglects the often bitter struggles over the nation’s direction and the enormous consequences of such debates. Moreover, it is one that neglects the role played by legions of others whose names aren’t known by all: the abolitionists who pushed for emancipation long before Lincoln signed the proclamation and the organizers who mobilized blacks across the South to boycott buses and march across bridges.

At its heart, politics is the process by which people make collective decisions, and as such, is essential to democracy. The question is what kind of politics we embrace. It can be about ideas, or it can be about itself. It can be about the direction of a nation, or about who wins an endless battle for control. Without political arguments, organizing and debate, we are left with the option of supporting those who claim the mantle of heroism, or patriotism or honor without questioning what those terms mean. To follow demagogues like Beck without engaging their arguments is to confirm the founders’ worst fears about democracy.

"Who are we now?" Beck asks in his video. The answer is that we are a democratic nation in which politics is an essential part of the governing process. It is not always noble and uplifting. It is not always honorable. But it does not follow that politics in and of itself is dishonorable. Where are our Kings, Washingtons, Jeffersons, Franklins, Lincolns? They are running for Congress, arguing in court, organizing their communities. In other words, engaging in the political process rather than shunning it.

Shares