In his Sunday column, Thomas Friedman offered an argument that has been made many times before. It goes something like this: Our country faces serious problems, Democratic and Republican politicians in Washington aren’t fixing them, and Americans are running out of patience. Therefore, a new party is on the way.

Specifically, Friedman supplied this prediction: "Barring a transformation of the Democratic and Republican Parties, there is going to be a serious third party candidate in 2012, with a serious political movement behind him or her -- one definitely big enough to impact the election’s outcome."

Brendan Nyhan has done a really good job cataloging forecasts like this over the last few years, and explaining why they’re pretty much all doomed to go unrealized. And Steve Benen smartly identifies the basic inconsistency of Friedman’s vision; the agenda that his "revolution" of the "radical center" would pursue is actually pretty close to the undiluted vision of Barack Obama and Democrats in Congress -- a vision that has been watered down and derailed by unified Republican obstructionism.

What’s most interesting, though, is that there is in recent history a fairly solid precedent that illustrates the folly of Friedman’s thinking: the 1980 election.

Back then, the Republican Party was going through the same internal upheaval that it now faces, with restive conservative activists declaring war on a party establishment that, they believed, was insufficiently committed to ideological purity. Once a party of spendthrift Yankee moderation and small-town Rotarians, the "New Right" -- emboldened by Ronald Reagan's near-miss challenge of Gerald Ford in 1976 -- was rapidly remaking the GOP as a fundamentally right-wing party that catered to the racial and religious politics of the South and the cultural resentments of white ethnics in the north. Longtime Republican officeholders like Clifford Case and Jacob Javits were purged in primaries, while Reagan easily dispatched George H.W. Bush, who ran with the blessing of the old Rockefeller wing of the party, in the ’80 presidential primaries.

At the same time, Jimmy Carter’s presidency was a mess, with high unemployment, inflation and interest rates (not to mention the hostage situation in Iran) conspiring to drag his approval ratings well under 40 percent. To most voters, Carter had been a profound disappointment. And within the Democratic Party, he was accused of selling out the organized labor and the traditional New Deal coalition, giving rise to a primary challenge from Ted Kennedy, which Carter eventually held off.

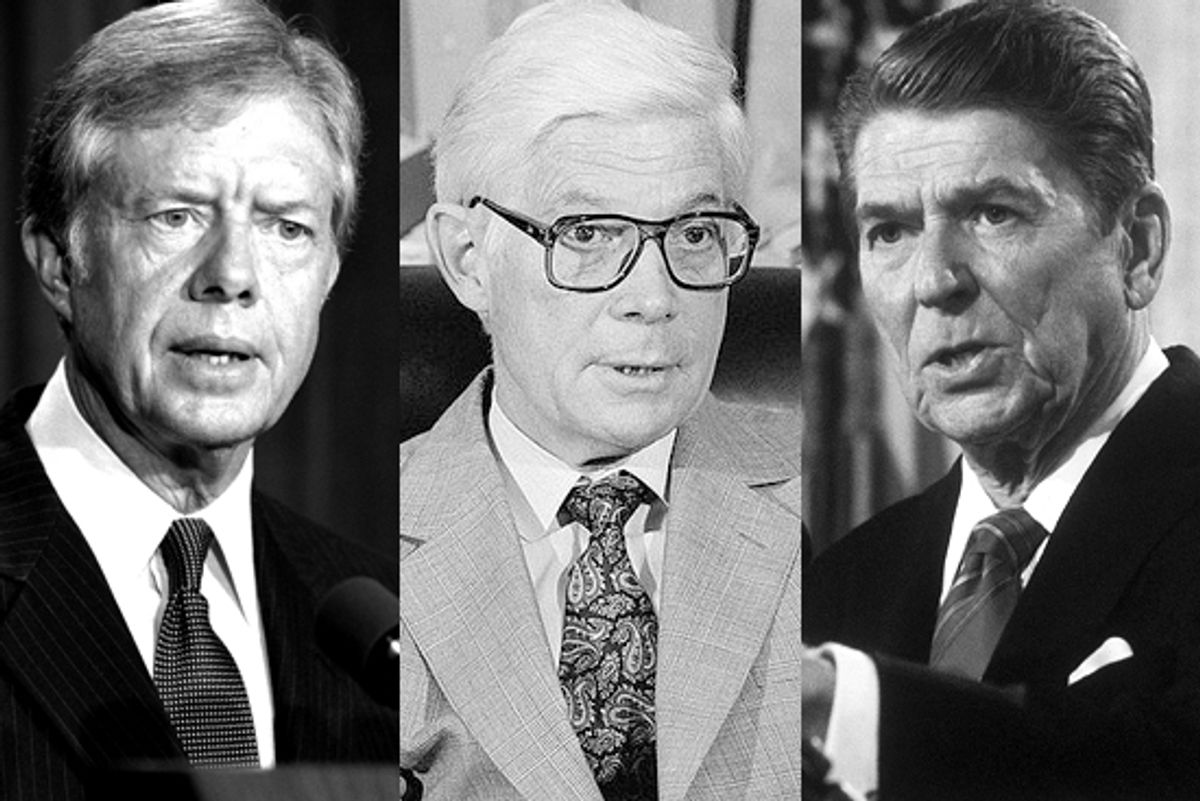

In other words, the conditions were seemingly optimal for a third-party movement: The Democrats (who also enjoyed sizable House and Senate majorities) had proven they couldn’t govern, but the Republicans had gone off the ideological deep end. Enter John Anderson, a liberal Republican congressman from Illinois who gave up his no-shot bid for the GOP presidential nomination in March and announced that he’d run as an independent in November. His move was celebrated by "radical centrist" Friedman-ish pundits, and -- at least initially -- by plenty of voters, too. At one point in the spring of ’80, Anderson scored 24 percent in a trial heat with Carter and Reagan. It was only the beginning, he promised.

But it was actually the beginning of the end. Ballot access and fundraising presented significant barriers to Anderson; glowing treatment by editorial boards and columnists can only get you so far. Voters quickly concluded that the real game was between Reagan and Carter and chose sides accordingly. By October, Anderson’s support had dropped under 10 percent (even after he and Reagan staged a one-on-one debate televised by all three networks), and he finished with just 5.7 percent. Not for the first (or last) time, voters had shown that they liked the idea of a third party more than they were actually willing to vote for one.

The movement that Friedman is now predicting depends on the same basic conditions that defined 1980 being present in 2012. When it comes to the GOP side, this is probably a safe bet: The party that has nominated Sharron Angle, Christine O’Donnell and Rand Paul in 2010 is not likely to discover pragmatism in the next two years. Whether Obama is perceived in '12 as the failure that Carter was in '80 remains to be seen; if the economy improves significantly between now and then, the question is moot. But even if he is, Anderson's example shows the likely outcome for any third-party candidate attempting to capitalize on the seeming uniqueness of the moment.

Granted, individual third-party candidates occasionally manage to win some major statewide races. But the independents who accomplish this are typically well-established figures in their states (or, failing that, they have the money to make themselves well-established figures) and they often merely displace a major party candidate. Think of Lowell Weicker, a former three-term senator, launching "A Connecticut Party" and winning Connecticut’s governorship in 1990 on the strength of Democratic defections. It was an impressive individual feat, but it did nothing to establish a third-party foothold in the state; four years later, Weicker’s lieutenant governor, Eunice Groark, sought to replace him and received less than half the support Weicker did. That was pretty much the end of “A Connecticut Party.”

In this sense, an independent with a powerful personality and deep pockets could make a real dent in certain presidential races. If the conditions are right (that is, if the economy hasn’t turned around) and if he were willing to run, Michael Bloomberg could plausibly score a significant chunk of the vote in ’12 (more than Anderson in ’80, but probably not enough to win). But this would be a tribute to his endless resources and the electorate’s anxiety, not a signal that a viable new party was rising -- something the inheritor of whatever party Bloomberg might create would learn in 2016.

Shares