The Army earlier this year steered a $31 million contract to a psychologist whose work formed the psychological underpinnings of the Bush administration's torture program.

The Army awarded the "sole source" contract in February to the University of Pennsylvania for resilience training, or teaching soldiers to better cope with the psychological strain of multiple combat tours. The university's Positive Psychology Center, directed by famed psychologist Martin Seligman, is conducting the resilience training.

Army contracting documents show that nobody else was allowed to bid on the resilience-training contract because "there is only one responsible source due to a unique capability provided, and no other supplies or services will satisfy agency requirements." And yet, Salon was able to identify resilience training experts at other institutions around the country, including the University of Maryland and the Mayo Clinic. In fact, in 2008 the Marine Corps launched a project with UCLA to conduct resilience training for Marines and their families at nine military bases across the United States and in Okinawa, Japan.

Government contracting regulations allow sole-source contracts, but only under very limited conditions, such as when only one company has the ability to do the needed work, according to Trevor Brown, a contracting expert at Ohio State University.

Brown said inappropriately awarding sole-source contracts is an "endemic" problem throughout the Department of Defense.

"I am not an expert on resilience training," he said, "but I know enough to know they could have put out a tender, and my guess is they would have gotten a number of bids. My first reaction was that there is a market for this stuff."

Army resilience training is the pet project of Army Chief of Staff Gen. George Casey, previously the commander of U.S. forces in Iraq during the darkest days of the war there, from July 2004 through February 2007. Army sources say the director of the Army's resilience program, Brig. Gen. Rhonda Cornum, rammed the training contract through the Army bureaucracy on Casey's behalf.

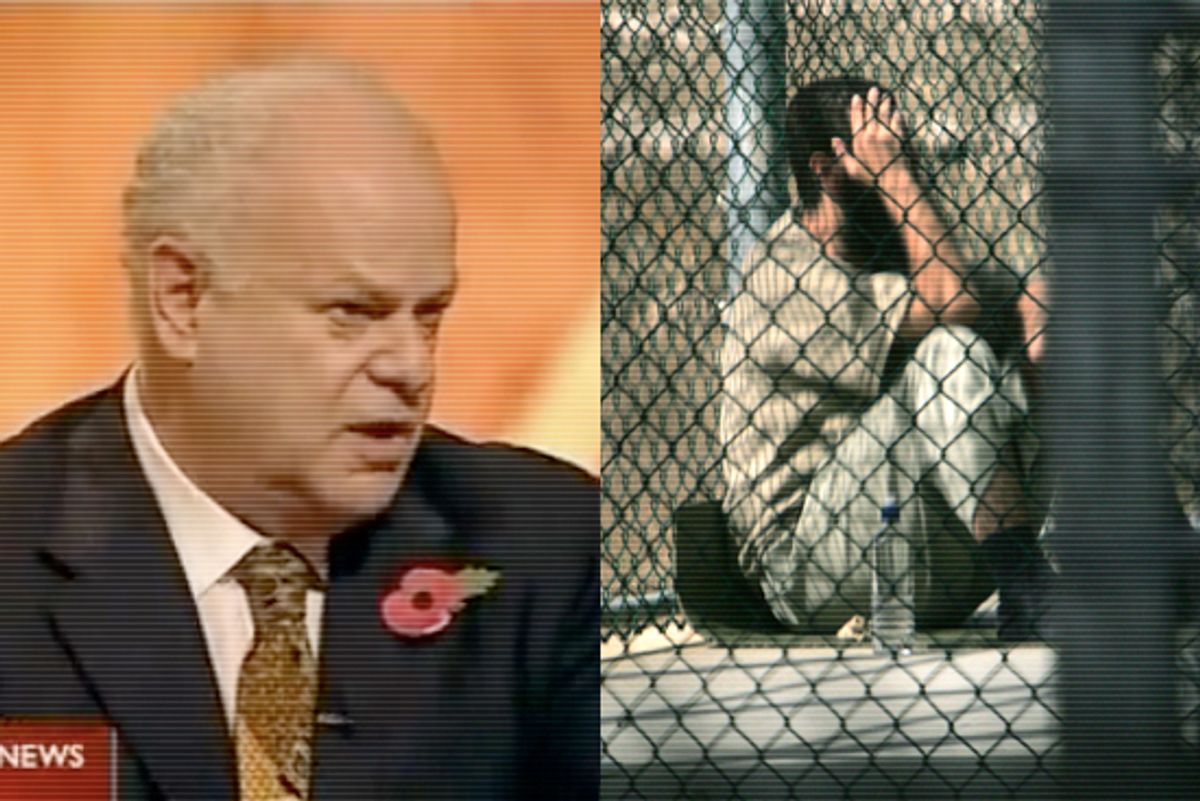

Seligman is most famous for his work in the 1960s in which he was able to psychologically destroy caged dogs by subjecting them to repeated electric shocks with no hope of escape. The dogs broke down completely and ultimately would not attempt to escape through an open cage door when given the opportunity to avoid more pain. Seligman called the phenomenon "learned helplessness."

Government documents say that the goal of Bush-era torture was to drive prisoners into the same psychologically devastated state through abuse. "The express goal of the CIA interrogation program was to induce a state of 'learned helplessness,'" according to a July 2009 report by the Justice Department's Office of Professional Responsibility.

Seligman, described as politically conservative by a psychologist who knows him well, once chastised his fellow academics for "forgetting" 9/11. "It takes a bomb in the office of some academics to make them realize that their most basic values are now threatened, and some of my good friends and colleagues on the Edge seem to have forgotten 9/11," Seligman once wrote on the Edge Foundation website. In that post, Seligman was arguing that any science advisor to the president "needs to help direct natural science and social science toward winning our war against terrorism."

Previous reports have explored how Seligman's fingerprints show up on the CIA and military torture programs -- including his interactions at key moments with individuals and institutions that helped set up and carry out government torture. Seligman told Salon he never intended for the government to use his ideas for torture and described the timing of the meetings as coincidental.

Understanding Seligman's connection to torture requires a bit of background. Bush-era torture was designed by a small group of current and former military psychologists who had been training elite U.S. soldiers to resist torture, an effort that has been in existence in the military for decades in what is called the Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) program.

In late 2001, both the CIA and the Pentagon first requested interrogation assistance from various SERE psychologists, according to a November 2008 report by the Senate Armed Services Committee and a 2004 CIA inspector general report. A small group of those SERE psychologists agreed to reverse-engineer their torture-resistance training tactics into brutal interrogation methods.

Seligman shows up early on. In December 2001, one of the SERE psychologists who helped establish and run the CIA torture program, James Mitchell, attended a small meeting at Seligman's house along with Kirk Hubbard, then the CIA's director of Behavioral Sciences Research. The New York Times has described this meeting as "the start of the program."

In a lengthy correspondence with Salon over the previous months, Seligman described that meeting at his house as a small gathering of professors and law enforcement personnel as well as at least one "Israeli intelligence person," to conduct an academic discussion about the so-called war on terror. "It was about isolating Jihad Islam from moderate Islam," Seligman said of the meeting. "It did not touch on interrogation or torture or captured prisoners or possible coercive techniques -- even remotely."An interview with another attendee as well as an agenda for that meeting, obtained by Salon, support Seligman's description of that meeting.

Seligman said he interacted with Mitchell at that meeting infrequently, but does recall the SERE psychologist "telling me that he admired my work at a coffee break."

Another interaction between Seligman and the architects of Bush-era torture came a few months later, in the spring of 2002. Jane Mayer's 2008 book "The Dark Side" shows that Seligman made a three-hour presentation at the Navy's SERE school in San Diego in the spring of 2002. Mayer said Hubbard, the CIA official, was involved in arranging Seligman's presentation. Hubbard confirmed that in an e-mail to Salon.

In e-mails to Salon, Seligman said that Hubbard, the CIA official, also attended the presentation. So did Mitchell and Mitchell's partner in setting up government torture, another SERE psychologist named Bruce Jessen. Seligman said the audience included 50 to 100 SERE officials. "I was invited to speak about how American troops and American personnel could use what is known about learned helplessness to resist torture and evade successful interrogation by their captors," Seligman wrote.

Seligman did allude to discussions at that time with SERE officials about interrogating al Qaida suspects, but said those talks were limited because of security clearance issues. "I was told then that since I was (and am) a civilian with no security clearance that they could not detail American methods of interrogation with me," he wrote. "I was also told then that their methods did not use 'violence' or 'brutality,'" he wrote.

Seligman's colleagues estimate that the famous psychologist charges between $20,000 and $30,000 to present a speech. Seligman waived his fee when he presented to the SERE officials.

The Senate report says that at around the same time during that spring of 2002, Mitchell's partner, Jessen, wrote for the military a "draft exploitation plan" for use on detainees. The Senate report says that at the same time, a number of SERE officials became involved in developing the torture program. "Beginning in the spring of 2002 and extending for the next two years (SERE officials) supported U.S. government efforts to interrogate detainees," the Senate report says. "During that same period, senior government officials solicited (SERE) knowledge and its direct support for interrogations."

Another related thing was going on at the same time in the spring of 2002. The CIA had also just recently taken custody of al Qaida suspect Abu Zubaydah, the first so-called "high-value" detainee subjected to CIA abuse. Mayer's book documents how Mitchell, the SERE psychologist, led the team that tortured Zubaydah that spring of 2002. She quotes an unnamed source present at the scene who says Mitchell described his plans for Zubaydah "like an experiment, when you apply electric shocks to a caged dog, after a while, he's so diminished, he can't resist."

(Mayer's book also explores the ironic leitmotif of Bush-era torture: that SERE officials are not trained interrogators and the methods they employed were originally designed by Communists to produce forced confessions, not good intelligence.)

In his correspondence with Salon, Seligman said the CIA and military appear to have hijacked his learned helplessness work without his knowledge or consent. "I am grieved and horrified that good science, which has helped so many people overcome depression, may have been used for such dubious purposes," he wrote in an e-mail. "Most importantly, I have never and would never provide assistance in torture. I strongly disapprove of it."

Similarly, Seligman says he doesn't know anything about how or why the military early this year steered the $31 million resilience-training contract to his psychology center with no other competition allowed. "I just don't know," Seligman wrote. "Government contracting is way above my level of knowledge or competence."

"You will need to ask General Cornum and (Army Chief of Staff.) Gen Casey about their process," Seligman added.

Gary Tallman, an Army spokesman, said in an e-mail that the Army steered the contract to Seligman for the benefit of soldiers. "The decision not to compete was affected by a compelling reason to execute this contract as quickly as possible, as the impact of current operations (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder [PTSD] incidents) and a suicide rate reported to be sixty percent higher than in 2003 posed significant concern for the well-being of our Soldiers," Tallman wrote. He said the contract also went to Seligman because the psychologist had "the only program available that demonstrated it could meet stated requirements such as 'longitudinal efficacy in randomized clinical trials, with improvement well documented in published research.'"

Tallman said Casey and Cornum declined Salon's interview request.

Shares