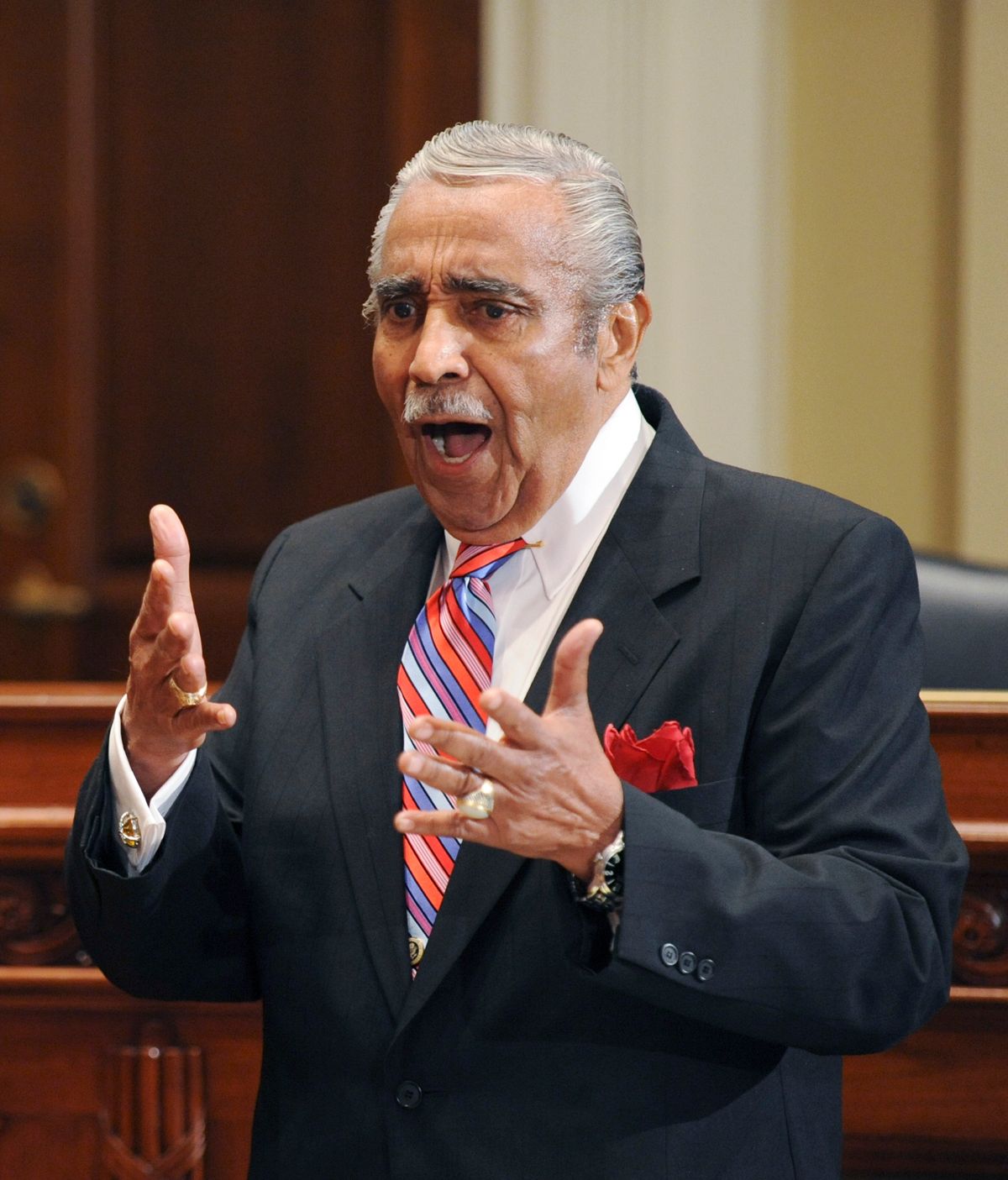

There was something unnerving about the scene that played out as Charlie Rangel's House ethics trial concluded Thursday afternoon.

An ethics subcommittee had already found Rangel guilty (unanimously) earlier in the week of violating New York City's building code, improperly using congressional letterhead, and failing to file his taxes correctly. The purpose of Thursday's full committee session was to determine Rangel's punishment. It was gaveled to order hours after Rangel, who had stormed out of the trial on Monday, released a statement throwing himself on the mercy of the committee -- and after Rangel used his clout to shut down rallies that his supporters had planned for him.

In other words, there wasn't much to accomplish on Thursday. Rangel's guilt had been established and he was seeking mercy. Plus, precedent clearly established that expulsion -- the most dramatic punishment available -- was not a viable option for the committee. Rangel would be receiving some sort of formal rebuke; the only thing left to do was to announce exactly what form that rebuke would take.

But none of this was going to stop Jo Bonner, a fifth-term Alabama Republican who serves as his party's ranking member on the ethics committee, from climbing on his high horse and -- with the cameras rolling, of course -- reading a blistering and at times petty eight-minute statement that repeatedly challenged Rangel's honor.

Rangel's transgressions, Bonner asserted, demonstrated "so little regard and respect either for the institution he has claimed to love or for the people in his district in New York that he has claimed to proudly represent for more than 40 years."

"Sadly, Madam Chairman," he said, "it is my unwavering view that the actions, decisions and behavior of our colleague from New York can no longer reflect either honor or integrity."

And on and on it went. At other points, Bonner claimed to be speaking on behalf of tenants in New York City and other cities and small businesswomen who had faced tax trouble. He also invoked a three-year-old incident on the House floor during which Rangel lashed out at one of Bonner's Republican colleagues.

As noted above, by the time Bonner spoke, Rangel had already been found guilty and it was already clear what his punishment would -- and wouldn't -- be. So it has to be asked: Why was Bonner so intent on rubbing it in? Certainly, simple partisan politics -- highlighting the ethical lapses of a prominent member of the other party -- had something to do with it. But it's also worth considering how the spectacle of their congressman lashing out at Rangel -- who in some ways is the face of black urban politics in America -- is likely to play with Bonner's constituents back home.

This is where things get a little troubling, because Bonner's 1st District was ground zero for the South's race-based transformation from Democratic stronghold to Republican bastion. I wrote about this evolution -- which was largely set in motion by the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 -- earlier this week. The South had been a uniformly Democratic region since Reconstruction, but the GOP's decision to nominate Barry Goldwater, who had joined segregationist Southern Democrats in their futile effort to block the Civil Rights law, prompted mass defections to the GOP in the fall of '64. Even as Goldwater racked up just 38 percent of the national popular vote, he carried five Southern states -- some by absurd margins (87 percent in Mississippi).

Bonner's 1st District illustrated this shift powerfully. Like just about every other Southern district, it had been represented by Democrats since Reconstruction. But because of civil rights, Goldwater carried it in a rout in '64 -- and his coattails helped a Republican, Jack Edwards, win election to Congress from the district. Edwards went on to hold the seat for 20 years; when he retired in 1984, he asked Sonny Callahan, then a former Democratic state senator, to switch parties and run to replace him. Callahan obliged.

The '84 GOP ticket that Callahan ran on was headed by Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. At one point, Bush was dispatched to campaign with Callahan. The vice president's visit was notable for what it revealed about how civil rights and race were reshaping the South's partisan balance. Here's how a Washington Post story at the time reported on Bush's campaign swing:

[T]the GOP strategy appears to play into old racial tensions in the Deep South. The Reagan administration has retreated from affirmative-action and civil-rights legislation embraced by the Carter administration, and the Democratic Party has tightened its links to the black community in this campaign.

According to a prominent Alabama Democrat who asked not to be identified, the Democratic Party, historically powerful in the South as the party of the whites, is now seen by many white and black southerners as the party of Jesse L. Jackson.

Mayor Emory Folmar of Montgomery, Ala., head of his state's Reagan-Bush finance committee, said the GOP saw a surge of white support in Alabama after the Democratic convention, and he attributed it to Jackson's prominence in the proceedings. Folmar said white southerners are uncomfortable not just with "the race thing" but also with Jackson's support of increased federal spending.

When Bush campaigned for House hopeful Sonny Callahan Monday before an all-white audience in Mobile, he drew boisterous cheers when he declared, "The party of Mondale and Ferraro and Tip O'Neill is not the Democratic Party that the people of Alabama remember . . . . The Democratic Party has left the people of Alabama."

Jackson, of course, had run for president as a Democrat in 1984. Callahan went on to win and to serve for 18 years in the House. One of his top aides during that time? You guessed it -- a man named Jo Bonner, who would succeed Callahan in the House after the 2002 elections.

This back story is what makes Bonner's speech on Thursday somewhat disturbing. The civil rights battle of the '60s and the GOP's subsequent emphasis on busing, affirmative action and "law and order" helped remake Bonner's once-Democratic district into a Republican stronghold. Bush summed it up perfectly in his '84 speech to an almost all-white crowd: The Democratic Party of Jesse Jackson was "not the Democratic Party that the people of Alabama remember."

So when Bonner launches a very public, very unnecessary attack on a black Democrat from Harlem, it's worth keeping in mind the effect it's likely to have on more than a few voters back home.

Shares