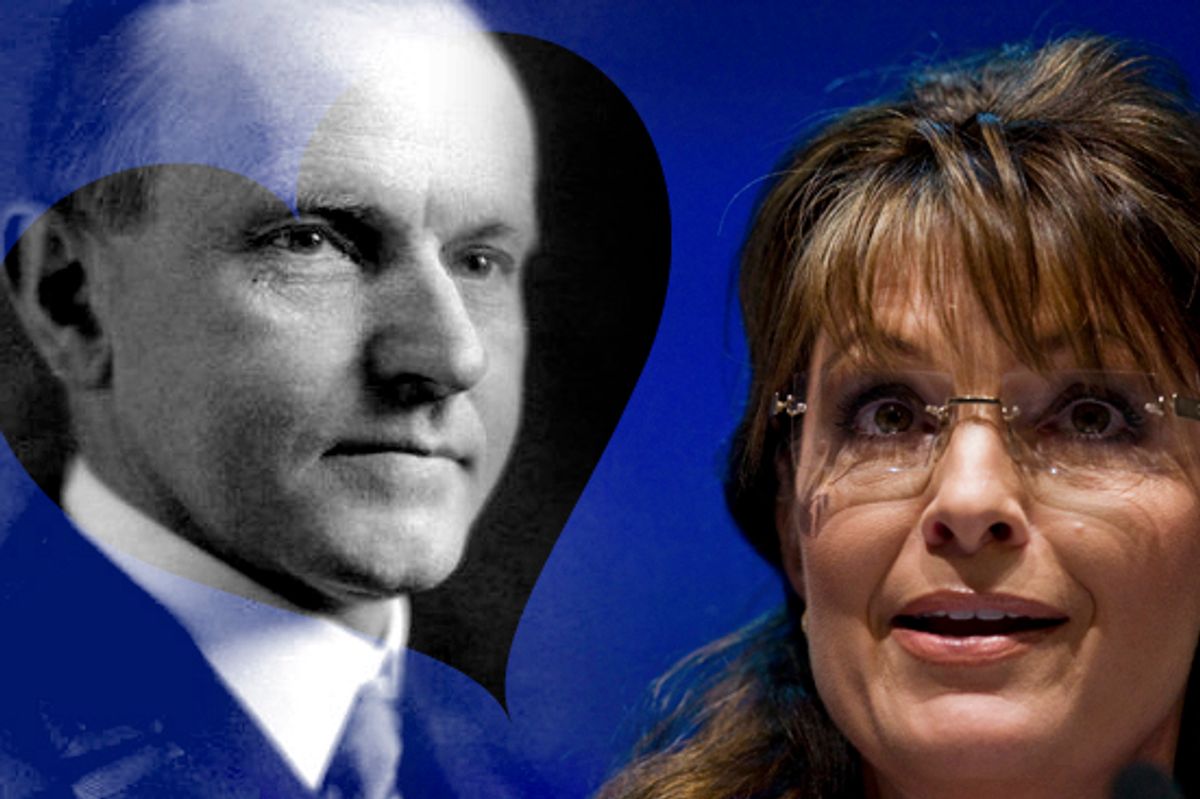

A reader who knew only the author and title of Sarah Palin’s new book, "America by Heart," would in all likelihood be able to predict many of the delights contained within: self-justifying accounts of her behavior on the 2008 campaign, snarky jabs at President Obama, paeans to the Alaska grizzly. Rapturous words for Calvin Coolidge, however, would probably not be among the expected finds. And yet peppered through Palin’s new volume of ruminations lies a handful of admiring references to our 30th president. The oddity is worth pondering.

To most people today, Coolidge is little more than a cartoon. If he’s remembered at all, he’s the grim-faced "Silent Cal," the man said by Theodore Roosevelt’s daughter Alice to have looked as though he had been weaned on a pickle. His taciturn style provoked no end of jokes and anecdotes. One hostess, aware of the president’s laconic reputation, was said to beseech him at an event, "I made a bet today that I could get more than two words out of you." Not missing a beat, Coolidge replied, "You lose."

There’s no evidence in "America by Heart" to suggest that Palin has dug much beyond this familiar lore about Coolidge. It’s hard to believe that she’s well-versed in the achievements of his presidency, whether the Dawes Plan to aid a debt-ridden Europe or the unprecedented mobilization of federal resources to deliver relief to victims of the 1927 Mississippi flood. She may not know the finer points of his economic policies. Coolidge seems to appeal to her, rather, because of his talent for evoking the values of a small-town America that was disappearing even during his presidency. Three times she cites his speech on the 150th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence ("I highly recommend it," she burbles) in which he swears by the timelessness of the ideals of equality and popular sovereignty that it uncontroversially avows.

Yet Palin’s name-checking of our 30th president is less corny than it seems. For decades, since the arrival in power with Ronald Reagan of so-called movement conservatives, Coolidge has been a patron saint to the right — a symbol of patriotism and piety, of hard work and thrift, and not least of low taxes and minimal government. When Reagan moved into the White House in 1981, he removed the portraits of Thomas Jefferson and Harry Truman in the Cabinet Room and put up those of Dwight Eisenhower and Coolidge instead.

For Reagan, who was a boy during Coolidge’s presidency, Silent Cal was "one of our most underrated presidents." Throughout his two terms in office, including the convalescence after his 1985 cancer surgery, Reagan perused Coolidge speeches and biographies. His staff brought to the White House the conservative writer Thomas Silver, whose 1982 book "Coolidge and the Historians" argued that liberal scholars had given Coolidge a bum rap. Reagan agreed. "I happen to be an admirer of Silent Cal and believe he has been badly treated by history," he wrote to a correspondent. "I’ve done considerable reading and researching of his presidency. He served his country well and accomplished much." Like Palin, Reagan drew on Coolidge’s homilies for his own statements.

The president was hardly the only Republican in Washington to find a model in the neglected Coolidge. Wall Street Journal editorialist Jude Wanniski, the apostle of supply-side economics, viewed Coolidge as an unsung prophet for his relentless efforts to cut taxes on the rich. The columnist Robert Novak ranked Coolidge as his second-favorite American leader — after Reagan, of course. GOP consultant Roger Stone hosted annual celebrations of the former president on July 4, which happened also to be Silent Cal’s birthday. The cult of Coolidge remained alive, if largely undetected, for many years thereafter. In September 2006, I was invited to an evening titled "Coolidge: A Life for Our Time," hosted by the Heritage Foundation, featuring a premiere screening of what was touted as "the first film ever made of the personal and political life of Calvin Coolidge."

Coolidge retains this mystique because he reconciled two different strains of conservatism and two different factions of the Republican Party. His approval of the decade’s kinetic capitalism pleased Chamber of Commerce types. But economic growth also has a way of unleashing cultural change, and Coolidge’s flinty New England virtue reassured traditionalists worried about moral decay during a time of the "new woman" and the "new Negro," of the Scopes trial and jazz. "We were smack in the middle of the Roaring Twenties, with hip flasks, joy rides, and bathtub gin parties setting the social standards," wrote Edmund Starling, Coolidge’s Secret Service agent and daily walking companion. "The president was the antithesis of all this and he despised it." Despite his reputation for silence, moreover, Coolidge was a skilled speechmaker — a prizewinning orator as a student and the last president to write most of his own remarks — and he excelled especially at the patriotic homilies that Sarah Palin seems to admire.

But Coolidge’s vogue on the right goes beyond the conservative principles he extolled; it lies in his conception of the presidency. He took office at a time when Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson had transformed the executive branch, actively using their powers to restrain big business and secure a measure of fairness in economic life. Coolidge, in contrast, believed in a small federal government, a passive executive and light regulation of business. "If the federal government were to go out of existence," he said, "the common run of people would not detect the difference." The main legislative battles of his presidency were to implement the tax cuts favored by his plutocratic Treasury Secretary Andrew W. Mellon. He even balanced the budget.

There is another reason, of course, that Coolidge — and not Warren Harding or Herbert Hoover, the other conservative Republicans of the interwar years — has become a hero to the contemporary right. Harding, who was probably more conservative than Coolidge, was discredited by the Teapot Dome affair — a wide-ranging scandal that tainted several of his closest aides. Hoover, who put the small-government philosophy into effect at an hour of crisis, saw it fail utterly. They do not appear in Sarah Palin’s new book.

Coolidge, in contrast, presided over six and a half years of economic growth, which was even called the "Coolidge Prosperity." He left office in March 1929, seven months before the crash. If he left no towering achievements as president, neither was he tarred by corrupt cronies or by a callous indifference to the plight of the destitute. And if historians note that Coolidge’s hands-off presidential style contributed, in its own way, to the miseries of the Great Depression — well, who today really knows the finer points of his economic policies?

David Greenberg is a professor of history at Rutgers University and the author of "Nixon’s Shadow" and "Calvin Coolidge." In 2010-11, he is a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington.

Shares