My colleague Alex Pareene recently dubbed the New York Times' Matt Bai "the political reporter who doesn't believe in political science." Not to pile on or anything, but it doesn't seem that Bai believes in -- or understands much about -- political history, either.

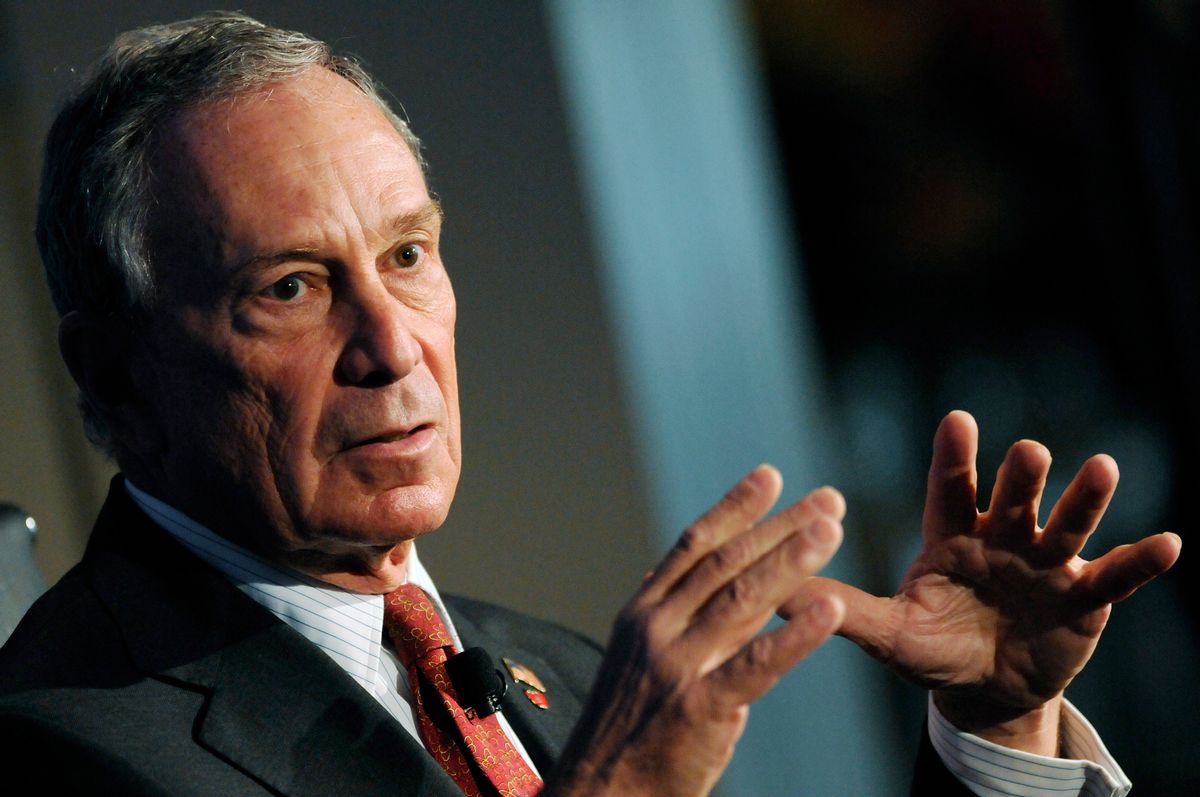

The main idea of Bai's latest piece is that most speculation about a potential independent presidential bid by Michael Bloomberg is flawed because it assumes that the New York mayor would need to build a third-party organization of his own -- perhaps one that could grow out of the "No Labels" organization he addressed on Monday -- in order to run. This used to be true, Bai tells us, but not anymore, because "the Web has created an increasingly decentralized and customized society" that has pushed voters away from large institutions. Thus, there is an "unprecedented" opportunity for an independent candidate to run without a traditional organizational infrastructure:

All of this might just explain why Mr. Bloomberg would reject the idea of running in 2012 while at the same time continuing to level a candidatelike critique of the status quo in Washington. Since he wouldn’t need to build a party organization in the way Mr. Perot did in 1992, Mr. Bloomberg can wait considerably longer — perhaps even until the 2012 primaries — to assess whether a campaign might be viable. In the meantime, ruling himself out as a candidate only enhances his credibility as a national reformer.

This is just aggressively ignorant history. Bai seems to believe that Ross Perot, the Texas billionaire who nabbed 19 percent as an independent in '92, created his Reform Party in advance of that election. He didn't. The Reform Party was launched after the '92 election as an attempt to capitalize on Perot's surprisingly strong showing and to keep the momentum alive.

Bai seems completely unaware that Perot's '92 candidacy sprung up exactly the same way that he imagines a Bloomberg '12 effort starting; Perot was on no one's White House radar -- and had taken no steps to fund or build any kind of political organization -- until Feb. 20, 1992, when he appeared on "Larry King Live" and, after some prodding from the host, finally declared that "if you (the people) want to register me in all 50 states, I'll promise you this: Between now and the conventions, we'll get both parties' heads straight." Even though few Americans had heard of him, Perot's challenge sparked a grass-roots phenomenon: Local petition drives, with no official connection to Perot or any official Perot organization, were launched across the country. Within weeks, Perot was on course to qualify for every state ballot -- and he was steadily moving up in polls against George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton. By the end of May, he was leading the three-way horse race with nearly 40 percent of the vote. Then Perot began to wilt under the media spotlight, dropped out during the July Democratic convention, reemerged at the end of September, performed strongly in the three presidential debates, and ended up with the biggest share of the popular vote any independent candidate had achieved since Teddy Roosevelt in 1912.

The entire Perot saga, by Bai's logic, shouldn't have been possible. After all, the Web revolution that, according to his thesis, has eroded Americans' loyalties to political parties was in its infancy back in '92, a few million people dialing into Prodigy and CompuServe with their 2400 BPS modems.

The reality, of course, is that Perot in 1992 very much represented the "break from the dictates of any party organization, mainstream or otherwise" that Bai believes voters are only now looking for. Perot's moment came about because of intense economic anxiety, which turned Americans against Bush, and the high negative poll ratings with Clinton, who was poised to win the Democratic nomination even after being hit with a barrage of scandals. Perot's supposed independence -- from both parties, from Washington, and from the political establishment in general -- stirred excitement. But even when he got serious about running, he didn't create an actual party or hold an actual convention; in fact, his fall campaign consisted mainly of a series of 30-minute nationally televised addresses (and some unusual 60-second ads, that featured long strings of text scrolling down the screen).

The Reform Party wasn't created until September 1995, after Perot hosted a convention of his remaining supporters in Dallas. (Perot's standing had been in decline since a disastrous CNN debate with Al Gore over NAFTA in November '93.) Ultimately, he baited Dick Lamm, the former Colorado governor, into seeking the new party's 1996 nod, but it was a trap. Perot wanted to run himself, but needed someone to beat up in order to make himself look stronger. No one was fooled and Perot made little mark in the '96 general election. Not only was he damaged goods, but the climate had changed; the economy was strong and Clinton was a popular incumbent. Perot received 8 percent. Jesse Ventura managed to use the Reform Party's line to win election as Minnesota's governor in 1998, but otherwise, the party steadily faded from view. And contrary to what Bai suggests, it did not exist in 1992.

The notion that our "decentralized and customized" society is threatening political parties in ways never before seen is apparently a Bai favorite. He built an October New York Times Magazine piece on Linda McMahon around it, claiming that it had made possible the WWE's Senate campaign. That piece was horribly flawed, as well, with Bai ignoring all sorts of Connecticut political history that undercut his thesis.

Shares