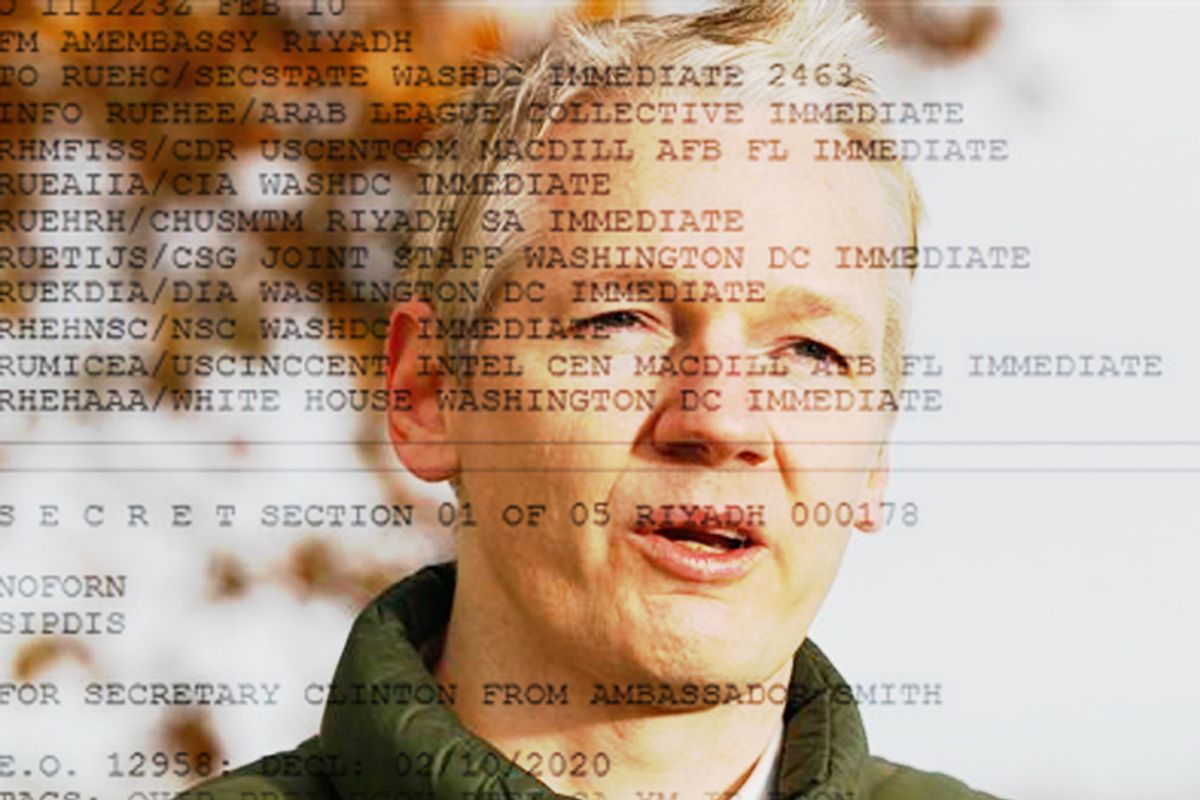

Julian Assange may not be Time's Man of the Year, but he almost certainly is a journalist -- at least as far as the First Amendment is concerned.

The Constitution’s First Amendment forbids Congress from making any law abridging either freedom of speech or freedom of the press. Some commentators and government officials have confidently asserted that Assange is not a journalist -- perhaps intending to imply that he does not enjoy the protections afforded by the First Amendment. But they are almost certainly incorrect.

Let us first dispense with the idea that Assange may not enjoy the safeguards of the First Amendment because he is not a United States citizen. The language of the First Amendment does not limit its protections to citizens, and the courts have never interpreted it that way.

Let us next dispense with the canard that Assange does not enjoy First Amendment protection because he is not objective, has a point of view, or is seeking to achieve a particular political outcome. As a historical matter, it is clear that objectivity has never been an indispensable characteristic of journalism. The ideology of journalistic objectivity emerged at the end of the 19th century as part of a broader cultural and intellectual movement. But for at least half of the history of American journalism, newspapers freely acknowledged that their judgments about news were influenced by partisan considerations. And today many established news organizations no longer even pretend to be neutral about the issues of the day. Others cling to a veneer of objectivity by presenting "both sides" of an issue while nevertheless presenting a clear point of view. More important than this history, however, is that grafting an "objectivity" requirement onto the First Amendment would subject freedom of expression to the subjective judgments of prosecutors and judges about whether a given journalist is sufficiently objective, thereby threatening to cripple press liberty.

Another claim made by some who dispute Assange’s right to First Amendment protection has to do with scale: "Real" journalists may disclose private or secret information selectively, in the context of a given story, while WikiLeaks is in the business (so to speak) of massive document dumps. Here again, there does not appear to be a reasoned basis for depriving WikiLeaks of First Amendment protections extended to others. The principles underlying the First Amendment do not suggest that its protections dissipate the more one engages in the activity it is designed to protect.

One potentially credible argument for denying WikiLeaks full First Amendment protection is that it is merely posting documents without adding its own analysis or commentary. Although I am not sufficiently familiar with the details of WikiLeaks’ website to evaluate the veracity of this claim, if it is true, it could provide a basis for prosecutors and courts to thread the constitutional needle and proceed with a case against WikiLeaks without running afoul of the First Amendment.

So is Assange a journalist? You and I are free to apply whatever standards we like when answering that question. But if the United States government decides to prosecute Assange, it will not have that luxury. Prosecutors and judges will have to put aside their subjective judgments about what constitutes journalism, and instead apply well-established constitutional principles to determine what protections, if any, the First Amendment affords Assange. And applied dispassionately -- without regard for one's personal feelings about Assange's actions -- those principles suggest he is entitled to whatever protections the First Amendment extends to his activities, just as if they had been undertaken by the New York Times.

That said, the protections of the First Amendment are not absolute -- far from it. Application of the First Amendment to WikiLeaks would raise the bar substantially for prosecutors -- and might result in an inability to convict Assange for violating U.S. law. But it would not end their case.

The Obama administration has important decisions to make when it considers whether and how to prosecute Assange. The government is appropriately concerned with protecting national security and preserving diplomatic initiatives. But the lines distinguishing professional journalists from other people who disseminate information, ideas and opinions to a wide audience have largely disappeared with the advent of the Web and inexpensive and powerful personal computers and software. WikiLeaks is just the beginning, and the government’s decision about how to proceed will have important implications for press freedom for years to come.

Shares