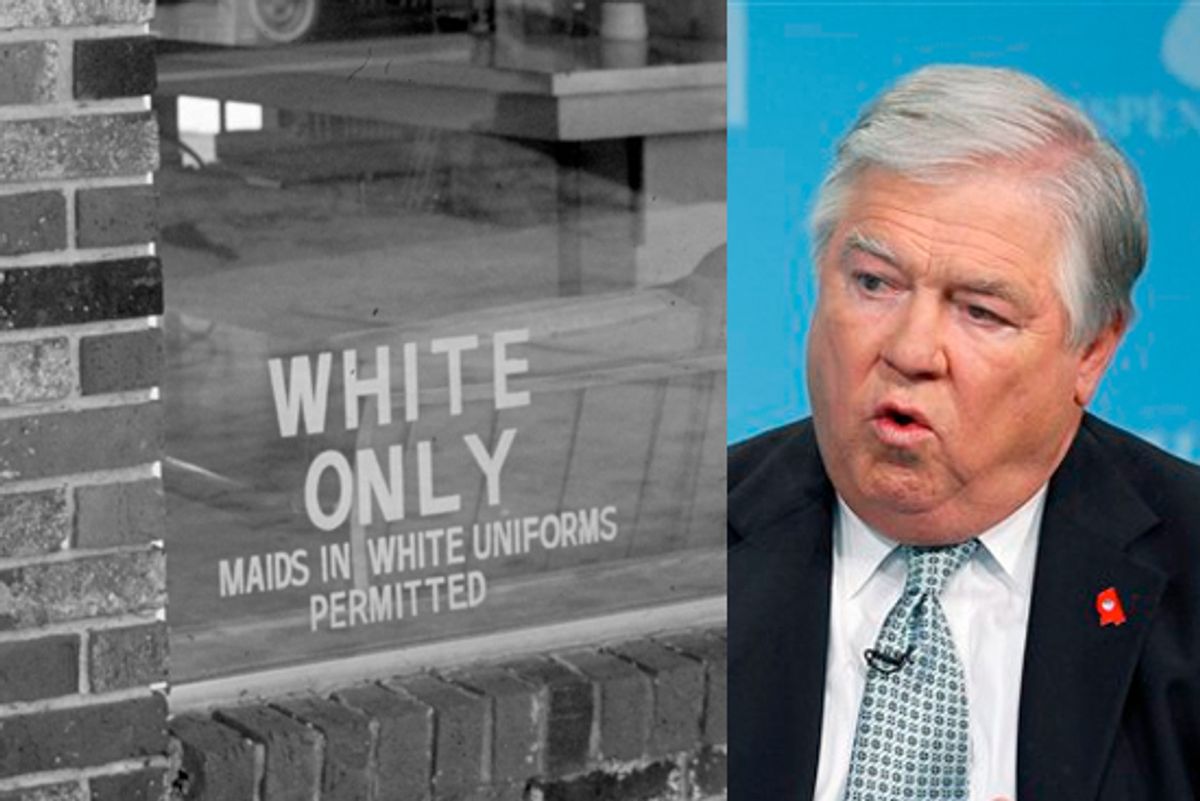

One of the most striking parts of the Weekly Standard profile of Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour published this month was the governor's recollection -- or, more accurately, non-recollection -- of what was going on around him when he was growing up in the segregated South in the 1950s and 1960s.

"I just don’t remember it as being that bad," Barbour said, in perhaps the most memorable line of the piece.

Now, a man who says he was a close childhood friend of Barbour in Yazoo City, Miss., has come forward with a strikingly different account of those years -- one marked by brutal and persistent injustice under segregation. Salon spoke with Steve Mangold, a retired San Jose public relations executive who wrote a letter to the Clarion-Ledger newspaper this week disputing Barbour's take on Yazoo City's history.

Mangold, who, like Barbour, was born in 1947, says he grew up a block away from Barbour and that the two were close friends through the end of junior high, when Mangold went off to a boarding school out of state and Barbour remained in Yazoo City to go to the local high school.

"I like Haley. He's one of the brightest, most charming people I have ever met in my life," Mangold says, while acknowledging that he disagrees with Barbour entirely on matters political.

In the Weekly Standard profile, Barbour marveled at the fact that Yazoo City's schools were desegregated without violence, unlike in many other towns in Mississippi. But for Mangold, whose parents were both physicians in Yazoo City, another local institution is in the forefront of his memory of that era: the hospital.

Built in the mid-1950s with federal assistance, the Yazoo City hospital was, at the insistence of the local White Citizens Council, a whites-only facility, Mangold says. As a child, he had the nighttime assignment of answering the back door at his parents' home, where they had their medical practice (whites came to the front door, blacks to the back). He would often see black residents with grievous injuries requiring emergency care -- but they had nowhere to go.

"There was no hospital in town where blacks could go. They would have to go to Jackson 40 or 50 miles away, and many died on the way," he says, adding that this state of affairs lasted for years.

Further, his parents became pariahs in town and their business was damaged because they had resisted the White Citizens Council petition that the hospital be whites-only.

"Threatening phone calls, dead cats on the lawn and other acts of intimidation combined to run my father out of town for two years," Mangold wrote in his letter to the Clarion-Ledger.

It was that same White Citizens Council that Barbour praised to the Weekly Standard:

“You heard of the Citizens Councils? Up north they think it was like the KKK. Where I come from it was an organization of town leaders. In Yazoo City they passed a resolution that said anybody who started a chapter of the Klan would get their ass run out of town. If you had a job, you’d lose it. If you had a store, they’d see nobody shopped there. We didn’t have a problem with the Klan in Yazoo City.”

But again, Mangold remembers things differently.

"What happened in Yazoo City was the White Citizens Council used economic power to try to intimidate blacks not to be uppity," he says. "When Haley says the White Citizens Council kept the KKK out -- it's an argument that doesnt make sense because the people who were in the White Citizens Council would have been in the KKK if they were into wearing sheets. There was very little distinction in my mind."

But, Mangold says, perhaps little of what was going on registered with Barbour. "He grew up and everything was hunky-dory because he wasn't involved with any of this."

Shares