Will conservatives restore America to constitutional government? The new Republican leadership in the House of Representatives has promised not only to begin the new congressional session by reading the Constitution in its entirety, but also to require that every new piece of legislation cite the passage in the federal Constitution that authorizes it.

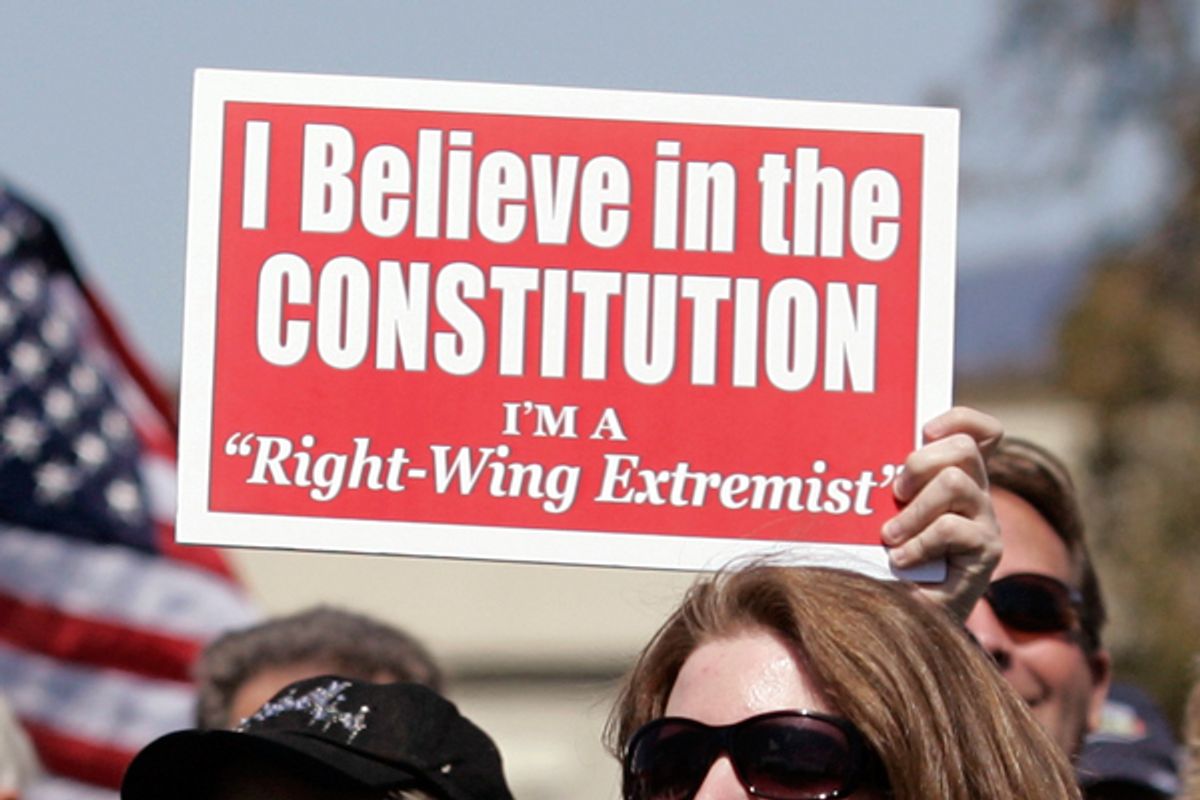

These gestures are certain to please the conservatives of the Tea Party movement who are the ascendant force in Republican primary elections. But Tea Party constitutionalism represents a deeply flawed understanding of America's founding, which ought to be based on the revolutionary idea of the power of the sovereign people to make and unmake constitutions of their design, not on superstitious veneration of particular constitutions handed down by wise demigods.

Tea Party constitutionalism blends several American traditions. One is the tradition of hostility to the federal government chiefly associated with the South, which adopted states' rights ideology in order to resist federal interference first in Southern slavery and then in Southern racial segregation. Now that the Republican Party, founded as a northern party opposed to the extension of slavery, is disproportionately a party of white Southern reactionaries, dominated by the political heirs of the Confederates and the segregationist Dixiecrats, the denunciation of many exercises of federal authority as illegitimate would have been predictable, even if the president were not a black Yankee from Abraham Lincoln's Illinois.

But there is more to the constitutional theories of the modern GOP than neo-Confederate ideology. Beginning with the adoption of the federal Constitution, some Americans have sought to promote reverence for this particular Constitution, while others have emphasized the power of the Constitution-making people. Thomas Jefferson thought that laws and constitutions should be updated frequently, while his friend and ally James Madison thought that constitutions and laws should be changed only infrequently in the interest of stability. John Adams thought that the founders of constitutions should be revered, as in ancient Greece and Rome.

Madison and Adams won the argument. The folk culture of American constitutionalism blends themes from 17th-century English Protestantism and 18th-century neoclassicism. From Protestantism comes the rejection of the "Catholic" idea of an evolving scriptural tradition interpreted by an authority -- the Vatican or the Supreme Court -- in favor of the idea that the Christian or American Creed is in danger of corruption if it strays too far from the literal words of the original, perfect revelation. According to the Washington Post, one Tea Party member in Louisiana "has attended weekend classes on the Constitution that she compared with church Bible study."

From 18th-century neoclassicism comes the idea that citizens of a republic must be taught that their constitutions are perfect and were handed down by superhuman lawgivers or "Legislators" -- Solon in Athens, Lycurgus in Sparta -- and must be preserved without alteration as long as the republic endures.

The blending of Protestant fundamentalism and neoclassical Legislator-worship explains the semi-religious reverence with which the Founders or Framers or Fathers of the Constitution have long been discussed in the United States. Other, similar English-speaking democracies -- not only Canada, Australia and New Zealand but modern Britain itself -- achieved self-governance or universal suffrage generations later, when these Protestant and neoclassical traditions had died out in their domains. The Canadians do not revere their first prime minister, John Macdonald, and to this day the British do not even have a formal, written constitution. Our Anglophone peers regard American constitution-worship as bizarre and quaint, like our fondness for displaying the national flag.

English-speaking democracies tend to be stable and free even when, like Britain, they lack a written constitution. But Latin American republics have been afflicted by dictatorship and civil war for generations in spite of having formal constitutions modeled on that of the United States. The contrast demonstrates that the true security for freedom is a culture of constitutionalism, not a particular constitution, or any written constitution at all. The details of a particular democratic political system -- presidential or parliamentary, bicameral or unicameral, unitary or federal -- are ultimately less important than the unwillingness of the citizens to resort to violence when they lose an election, unlike the Confederate ancestors of so many of today's white Southern Republicans, who tried to destroy the country upon losing an election.

The federal Constitution drafted in Philadelphia in 1787, as amended, is still in effect in the United States. In contrast, France is now under its Fifth Republic. An old joke has an American in Paris asking a bookseller for a copy of the French constitution. Irritated, the Parisian bookseller replies, "We do not sell periodical literature."

But the joke is on Americans, not the French. Indeed, the 50 states are very "French" in their populist approach to constitutionalism. Most states in the Union have gone through several constitutions, with no apparent harm. Many of today's state constitutions in the Northeast and West Coast date back only a few generations to the Progressive era, and show the influence of belief in apolitical, technocratic executives in the number of state officials appointed by a strong governor. At the other extreme, many constitutions adopted by the defeated Confederate "Redeemers" following the Civil War create weak state governments and feeble governors. The influence of Jacksonian populism accounts for the fact that in some states most executive branch officers and even state judges are directly elected.

In no state, to my knowledge, is there a cult of the all-wise Founders of the State Constitution, who drafted the most recent of several state charters. Few legislators, even few conservative Republicans, would be able to tell you the date at which their latest state constitution was adopted, much less name any of the drafters or ratifiers.

The treatment of state constitutions as mere charters of government to be periodically updated or replaced, not secular versions of holy scripture, gets it right. The essence of American republican liberalism is found in Jefferson's words in the Declaration of Indepedence: "That whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and and to institute new government, laying its foundations on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness." Here there is no implication that a perfect code of laws has been handed down to later generations by a superhuman generation of Lawgivers, who should be worshiped as demigods century after century. Constitutions are above ordinary statutes, to be sure, but both constitutions and laws are ordinary rules agreed upon by members of the sovereign people, not to promote their eternal salvation or to conform to some mystical law of nature discerned by philosophers, but to "effect their safety and happiness." Not only are later generations in a free and democratic republic likely to include as many intelligent, patriotic and virtuous people as the founding generation, but later generations have more knowledge of what works and does not work in politics in their country and other societies.

Of course federal laws should be constitutional. But if we as a people want the federal government to do something that the present constitution does not permit, let's amend the much-amended constitution once again, or replace it with a completely new constitution, as the states have frequently done. The U.S. Constitution is not the stone tablets of the Ten Commandments, and James Madison and John Adams were not Lycurgus and Solon.

Shares