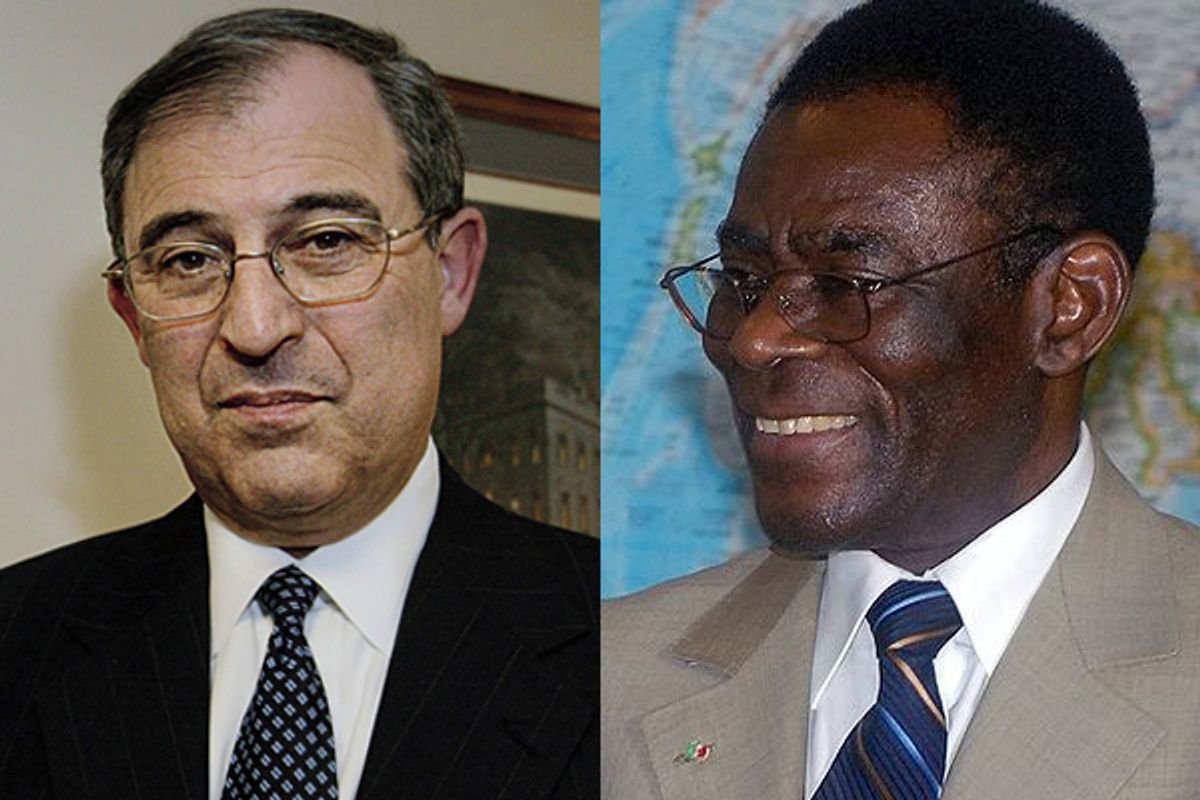

Last April, when Democratic lobbyist Lanny Davis was hired by the government of Equatorial Guinea, he declared himself the "reform counsel" for the longtime dictator of the small, oil-rich African nation. Davis' fee was $1 million per year plus expenses, and he and his client, President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, promised widespread reforms and a new respect for human rights.

But today, human rights advocates who track Equatorial Guinea tell Salon that nothing has changed there and that Davis appears to be engaged in little more than a whitewashing exercise designed to rehabilitate the image of the Obiang regime on the international stage. And despite a direct promise by Davis to a reporter in June that political prisoners in Equatorial Guinea would be released, that has not happened.

Davis, a former Clinton administration official who recently launched a new public relations firm called Davis-Block, is still retained on the Obiang account. That's in contrast to his work for the former president of Ivory Coast, who was also accused of human rights abuses and with whom Davis severed ties last week after scrutiny from Salon and others.

Obiang has ruled Equatorial Guinea since 1979, when he took over in a coup. In the last several presidential elections (the most recent was in 2009) , he won reelection with 95 percent or more of the vote. That's a fact about which Davis joked at an event in Cape Town, South Africa, in June where Obiang delivered a speech promising reforms. "I’ve kidded him he’d do better to win by 51 percent than 98 percent," Davis said.

The economic and human rights situations in Equatorial Guinea have been grim for years. Even as members of Obiang's family and regime have become fabulously rich from oil revenues, the majority of the population lives in extreme poverty.

A March 2010 State Department study reported the following human rights violations under Obiang: unlawful killings by security forces; torture of detainees and prisoners by security forces; life-threatening conditions in prisons and detention facilities; official impunity; arbitrary arrest, detention and incommunicado detention; judicial corruption and lack of due process; restrictions on freedoms of speech, press, assembly, association and movement; government corruption; violence and discrimination against women; suspected trafficking in persons; discrimination against ethnic minorities; and restrictions on labor rights.

(The report also includes gems like this: "According to Human Rights Watch, Teodorin Obiang, the president's son, spent more on luxury goods during 2004-2007 than the government's 2005 budget for education.")

So what's changed since Davis became "reform counsel" for Obiang? Nothing, according to Tutu Alicante, executive director of the Washington-based human rights group EG Justice.

"You have a government that is making all these promises to respect human rights -- to stop torturing, to stop arbitrary detentions -- but they continue to do those same things," Alicante tells Salon. "The June speech [by Obiang] was nothing but an attempt to wash his image before the international community. For people in Equatorial Guinea, nothing will change as a result of that speech."

In September, for example -- many months into Davis' work for Obiang -- Amnesty blasted the regime for the summary execution of four political opponents who had been abducted by Obiang's security forces in Benin. They were convicted of an attempt to assassinate Obiang after a "grossly unfair" trial and torture in detention, according to Amnesty. Meanwhile, two other "prisoners of conscience" were convicted as accomplices and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

That stands in marked contrast to a promise by Davis, reported in the Times in June, that political prisoners "will be freed."

"There is absolutely no doubt in anybody's mind that there are still political prisoners in jail," Alicante says, while noting that exact numbers are hard to come by because the regime holds such information close to the vest.

Asked by Salon what has changed in Equatorial Guinea, Davis wrote in an e-mail: "Several items -- the most significant Bishop Tutu's letter and final negotiations with Red Cross to return to EG for human rights and prison condition evaluations."

The letter is a reference to a missive from Archbishop Desmond Tutu welcoming Obiang's June speech and expressing hope that the government would follow through on the promised reforms. As for the Red Cross, it's unclear whether the group is in fact back in Equatorial Guinea. Davis declined to elaborate or answer follow-up questions.

Shares