So this is what it's come to for Joe Lieberman. Faced with meager poll numbers across the board, the man who once came within a few hundred accidental Buchanan votes of the vice presidency is now set to announce his retirement from the Senate after four terms.

Like any proud politician, he'll probably frame his departure as a voluntary act and insist that he could have won if he'd toughed it out. But make no mistake: When it came to his reelection prospects in 2012, Lieberman -- just like his longtime colleague Chris Dodd last year -- was simply out of options. He could run as a Democrat, he could run as Republican, he could run as an independent, but each path led to the same glum place. So he's hanging it up instead.

While his role as Al Gore's running-mate in 2000 earned him a spot in history (the first Jew ever to appear on a major party's national ticket), it's the decade that followed that campaign that figures to define Lieberman's political legacy. By embracing the Iraq War from the beginning and refusing to let go even as Americans -- and Democrats in particular -- turned on it, Lieberman earned pariah status within his own party, was stripped of its backing in his 2006 reelection campaign, and has spent the four years since as an "independent Democrat" who seems to delight in poking sticks in the left's eye. So it's hardly surprising that, for instance, the Daily Kos' Markos Moulitsas is now expressing satisfaction "that America and Connecticut will soon be rid of this useless sack of crap."

If you know how it started, it was almost inevitable that Lieberman's Senate career would end this way.

In theory, there shouldn't have been much room for a Democrat to run for the Senate in Connecticut in 1988. True, the seat that would be up belonged to a Republican. But the Republican in question was Lowell P. Weicker, Jr. -- the kind of Republican for whom the term RINO was invented.

Elected in something of a fluke in 1970, Weicker was one of the last of the authentic Rockefeller Republicans still standing after the Reagan revolution. A staunch supporter of abortion rights, gay rights, and school busing, he'd scored points with liberals early in his first term by refusing to toe the Nixon administration's line on the Watergate select committee. As the Reagan era dawned, Weicker found himself positively isolated in his party, battling the White House -- and an overwhelming majority of Republicans on Capitol Hill -- on school prayer, civil rights, Central America, and funding for education, AIDS research and the homelessness programs, to pick just a few areas. In its 1986 rankings, the venerable Americans for Democratic Action rated Weicker the most liberal Republican in the Senate, by far -- and 20 percentage points more liberal than his fellow Connecticut senator, a Democrat named Chris Dodd.

To the extent Weicker was in jeopardy as ’88 approached, the thinking went, it would be within his party. In his previous reelection campaign in 1982, he’d faced an initially formidable challenge from his right, with Prescott Bush, Jr. -- the brother of then-Vice President George H.W. Bush and the son of Prescott Bush, who’d represented the state in the Senate from 1952 to 1963 -- seeking to grab the GOP nomination from him. Early polls put Bush ahead by more than 20 points, but Weicker engineered a surprisingly dominant victory at the state party convention that July, keyed by fears that nominating a conservative candidate would cost the party a winnable Senate race like it had in 1980, when Republicans had nominated James Buckley. ("Weicker the winner" was the incumbent’s slogan. Shortly after the convention, Bush dropped out and Weicker went on to win a third term.

In the run-up to ’88, conservatives in Connecticut sought to organize another primary challenge, stirring speculation that Weicker might end up bolting the party to run as an independent or even a Democrat. But their plans fizzled toward the end of 1987, when state Senator Tom Scott opted not to run, citing need to raise $1.5 million. There would be no need for Weicker to switch parties; the Republican nomination – and, it was widely assumed, a relatively easy path to a fourth term -- was all his.

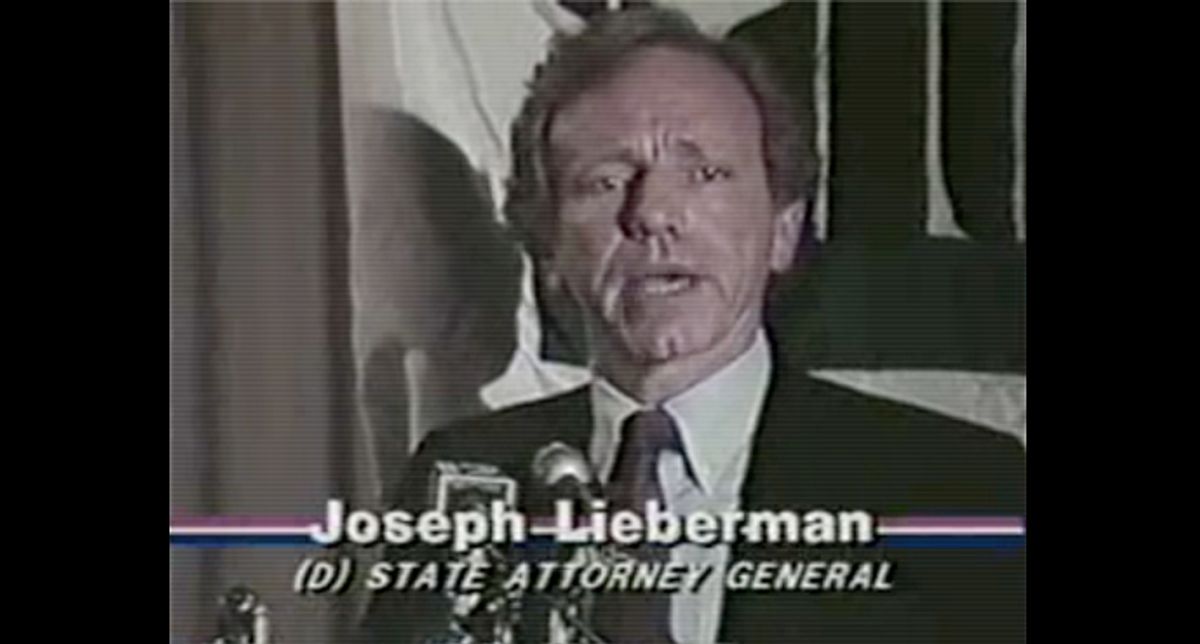

It was against this backdrop that, on the day before Thanksgiving 1987, Connecticut’s Democratic attorney general announced that he’d challenge Weicker. Lieberman was 45 years old and had been eying Washington for a while, having lost a 1980 congressional race to Republican Larry DeNardis. Two years after that, he’d bounced back to win the A.G.'s post, and in the 1986 general election, he'd won more votes than any other Democrat on the statewide ticket, including Governor William O’Neill.

Still, conventional wisdom had it that he’d be a sacrificial lamb against Weicker – that the race might help him build name recognition for a subsequent run for statewide office, but that the prospects of victory were remote because, as the New York Times put it, he would be facing "a Republican who has won strong support from unaffiliated voters and Democrats."

''I don't kid myself,'' Lieberman said. ''I'm an underdog. But it's a winnable race. This is an incumbent a lot of people don't like. There are lot of people who feel that 18 years is enough for a senator.''

Most political observers took this as hot air, but they probably should have known better. After all, even after surviving the Bush scare in '82, Weicker had only defeated his Democratic opponent, Rep. Toby Moffett, by 30,000 votes. And while some of that narrow margin could be chalked up to the national political climate -- soaring unemployment that stirred a midterm backlash against virtually anyone who shared President Reagan’s party label -- Weicker’s margins hadn’t been particularly impressive in 1976 or 1970, either. He had plenty of fans in Connecticut, but he was hardly the invincible pol many took him for.

But the real reason Lieberman was formidable was that, unlike every other big name Democrat in Connecticut, he was actually well-positioned to capitalize on Weicker’s liberalism. An unapologetic proponent of capital punishment (then a hot button issue, with crime rates soaring), he sided with the Reagan White House on aid to the Nicaraguan Contras, advocated a hawkish foreign policy, and played up his devout religious faith, leading some in the anti-abortion community to conclude that he shared their views. Another Democratic candidate would have worried about Weicker eating into his liberal base, but Lieberman set out to claim all of the turf to the incumbent’s right.

Weicker had made plenty of powerful enemies on the right, and without a candidate of their own on the GOP side, many of them began gravitating toward Lieberman -- most notably William F. Buckley, Jr., who was then still running the National Review. Buckley, along with his brother James and son Christopher, organized an anti-Weicker PAC and devoted himself – and his magazine -- to electing Lieberman. “Does Lowell Weicker make you sick?” asked one 1988 headline in the National Review.

''We want to pass the word that it's O.K. to vote for the other guy or stay at home,'' Buckley told the New York Times.

Buckley’s Lieberman cheerleading captured perfectly the upside-down nature of Connecticut’s 1988 Senate race, which also featured an enthusiastic endorsement of the Republican incumbent from the National Organization for Women. With polls showing him more popular among Democrats than Republicans, Weicker sought to make his estrangement from the GOP a general election asset. He showed up at the August Republican convention in New Orleans -- just to make it more dramatic when he announced that he was rejecting the party’s official platform. He lamented that religious conservatives like Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell were turning the GOP "into a one-note party," and adopted a new campaign slogan: "Nobody’s man but yours."

Steadily, Lieberman cut into Weicker’s lead. The Democrat’s fundraising was especially impressive, allowing him to air ads earlier and to stay on the air throughout the fall. He aggressively targeted Connecticut’s blue collar "Reagan Democrats," stressing his death penalty and foreign policy positions, and lampooned Weicker as a lazy, out-of-touch windbag. In one devastating Lieberman ad, Weicker was depicted as a sleeping bear who might occasionally raise his head to growl but who was mostly content to snooze. Riffing on Weicker’s slogan, Lieberman told crowds that the incumbent was simply "nobody’s man."

By the end of October the race was dead even. So was the result on Election Day. As the returns trickled in, neither candidate was able to establish a clear lead. Only when virtually every precinct had reported did it become clear that Lieberman had eked out a victory, by about 10,000 votes. Any one of several factors could have put him over the top, including a late surge in the state by Michael Dukakis, the Democrats’ presidential nominee. Dukakis had trailed badly in the weeks before the vote, but ended up holding Bush to a five-point margin -- potentially lifting downballot candidates like Lieberman. Plus, Weicker seemed to underperform in what should have been his base: the affluent, culturally liberal cities and towns in Fairfield County, Connecticut’s Gold Coast. Here, the culprit may well have been Lieberman’s attacks on Weicker for missing Senate votes and (supposedly) losing touch with his home state.

But the biggest single factor, it seemed, was Lieberman’s remarkable success in the state’s working class, culturally conservative areas -- particularly in the Naugatuck Valley near Waterbury. The same voters who had rejected the Democratic Party in favor of Reagan in 1980 and 1984 (and, in the case of the Naugatuck Valley, who had elected a fiercely conservative 27-year-old congressman named John Rowland in 1984) returned to the Democratic fold in 1988 to vote for the more conservative candidate: Joe Lieberman.

Weicker conceded the race with surprising grace (perhaps because he was already thinking ahead to 1990, when he waged a comeback bid for governor and won), while Lieberman headed off to Washington, where nearly two decades later he’d settle into the same role nationally that he first perfected in Connecticut back in 1988: Every Republican’s favorite Democrat.

Shares