Twenty years after Operation Desert Storm, George H.W. Bush and his war council gathered in College Station, Texas, on Thursday night for what amounted to an exercise in legacy enhancement.

The 1991 Persian Gulf War was, at the time, considered a thorough triumph. After Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in the summer of 1990, Bush began a months-long troop buildup and assembled an authentic international coalition aimed at pressuring Hussein to leave Kuwait. When a Jan. 15 deadline came and went, the war began -- and within weeks, ended. Despite dire warnings from opponents, Desert Storm ended up costing just 370 American lives, with Saddam quickly giving up Kuwait. Back home, the war seemed to lift the country's spirit and pushed Bush's approval rating above 90 percent. America, it was said, had finally kicked its Vietnam syndrome.

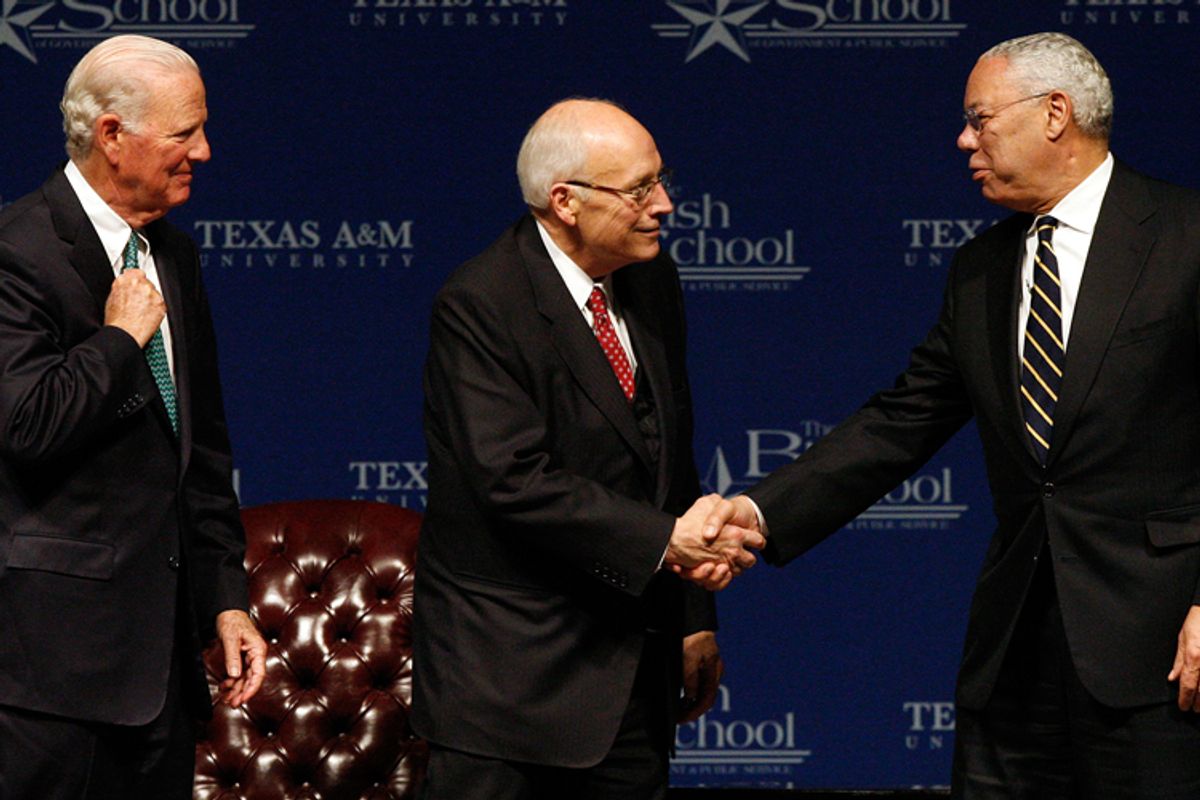

Politically, it was the high point of Bush's presidency. By the end of 1991, his approval rating had plummeted 40 points, thanks to a stubborn recession, and in 1992 he was defeated for reelection, drummed out with the lowest share of the vote for any incumbent since William Howard Taft. In speeches in the months and years after that defeat, Bush would frequently express his belief that "history will be kind to us," despite his rejection by the voters. Like any other president, legacy matters greatly to Bush, which explains Thursday night's highly choreographed reunion at Texas A&M's basketball arena. Among those joining Bush were Colin Powell, who was Joint Chiefs chairman in '91; Jim Baker, Bush's secretary of state; Brent Scowcroft, his national security adviser; and Dick Cheney, Bush's defense secretary. (Also: Dan Quayle!) As the New York Times' Elisabeth Bumiller summarized it:

For what could well be the last time, the major American decision-makers in the 1991 invasion that drove Saddam Hussein’s forces out of Kuwait gathered here on Thursday night, celebrating the 20th anniversary of what they quietly consider the "good" Iraq war — as opposed to the one that the second President Bush ordered in 2003.

There are two ways of thinking about the legacy of the '91 Gulf War.

You could certainly argue that the tragedy of the second Gulf War has illustrated the wisdom that Bush and his team showed in refusing to press on to Baghdad after liberating Kuwait. This left Saddam Hussein in power, but allowed most U.S. troops to return home quickly and spared the U.S. from having to oversee the rebuilding of a post-Saddam Iraq. As Baker noted at Thursday's event, "We would have been breaking our word to the rest of the world. You would have been turning a war of liberation into a war of occupation." (Cheney himself famously made the argument against going into Iraq back in 1994 -- even though he aggressively pushed the second President Bush to overthrow Saddam after 9/11.) In this sense, history has vindicated Bush -- because his own son refused to follow his example.

Of course, whether liberating Kuwait was really worth 370 American lives -- not to mention all of the non-American casualties -- is another matter. Plus, there's the issue of the Kurdish uprising that Bush encouraged at the end of the war -- and that Saddam brutally crushed while America did nothing. But the real problem with the "good" Gulf War was how easy it all seemed. To sell the country on the war, Bush spent months building up Saddam Hussein as the second coming of Hitler, vastly overstating the threat that Saddam posed globally and even regionally. Thus, when they saw how quick and (relatively) painless it had been to drive Saddam's forces out of Kuwait, Americans naturally asked, "Why don't we just get rid of this horrible man once and for all?"

This is why polls in the wake of the Gulf War -- and throughout the '90s -- showed that a majority of Americans believed Bush had ended the war too soon -- that he had erred in not sending troops to Baghdad. It was only after the second Bush actually did invade Iraq that Americans understood why his father had been so reluctant; back in the '90s, arguments about the dangers of occupying Iraq didn't resonate with most Americans. They'd seen how easy Desert Storm had been. Why would another Gulf War be any different?

This perception allowed neoconservatives and other hawks to spend the '90s slowly building the case for another war with Saddam. The 1998 Iraq Liberation Act, which made deposing Saddam Hussein the policy of the United States, was ostensibly a symbolic document. But that Bill Clinton felt powerless to oppose it spoke volumes about the political climate created by the success of the '91 war. There was, as we all now know, no connection between Iraq and the 9/11 attacks. But for 10 years, Americans had been exposed to one story after another about the evils of Saddam; no wonder they were so willing to believe those who claimed there was a connection. And no wonder the 2002 vote to authorize war was so lopsided in Congress. Back in '91, just 11 Senate Democrats had supported Desert Storm. But after that war's success, those who had voted "no" were ridiculed and pilloried. Faced with a similar vote in '02, a majority of Senate Democrats opted for war.

Shares