Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker has declared war on state workers, almost literally.

First, he proposed a state budget that would cut retirement and healthcare for workers like teachers and nurses, and strip away nearly all of their collective bargaining rights. But even more significantly, he announced last Friday that he had alerted the National Guard to be ready for state workers to strike or protest, an unprecedented step in modern times.

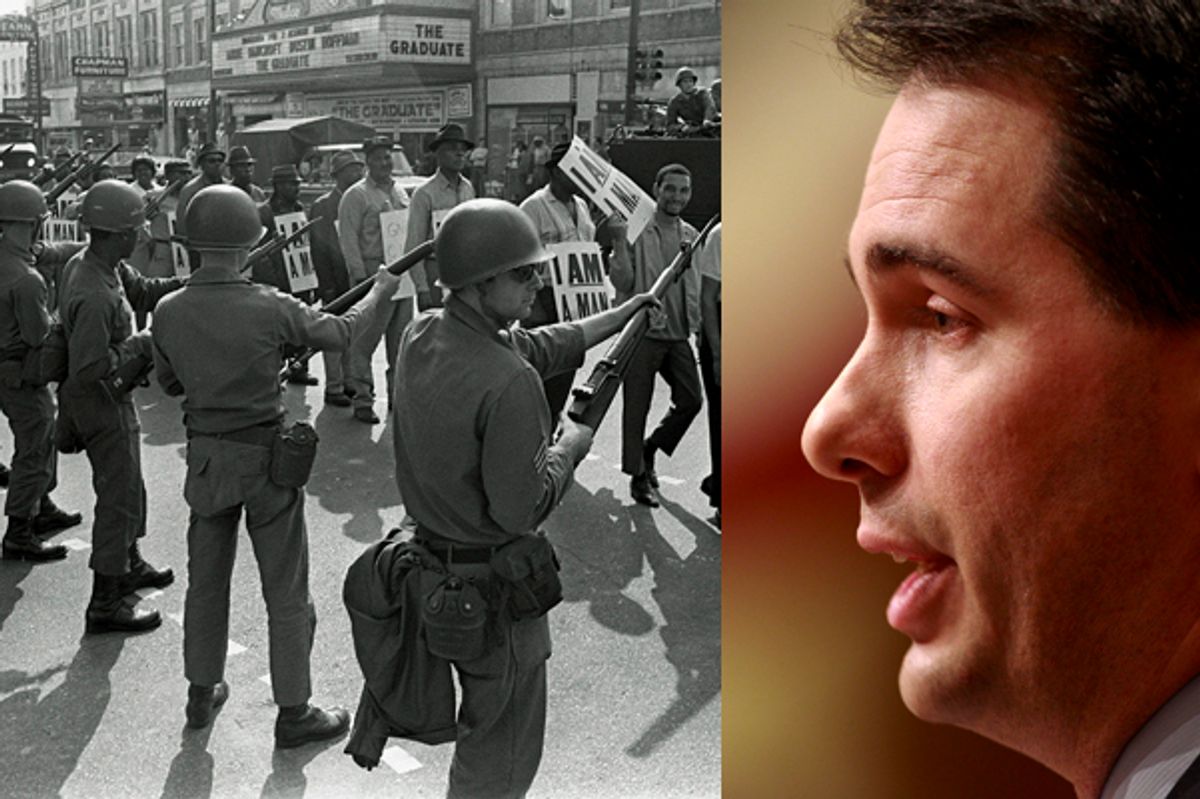

This would be the first time in nearly 80 years that the National Guard would be used to break a strike by Wisconsin workers, and the first time in over 40 years that the National Guard would be used against public workers anywhere in the country. The last time was the Memphis sanitation strike in 1968, just before Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination.

The outrage was immediate across labor message boards, Twitter and Facebook pages. Over the last two days, tens of thousands have protested in front of the capitol building in Madison in defiance of the governor, some even camping overnight.

To understand the visceral, emotional nature of this outcry, you have to understand the history of the National Guard and the labor movement -- and what this means for the relationship between labor and the state today.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, governors often mobilized the National Guard during strikes. Sometimes the Guard was genuinely neutral, assigned to buffer the dangerous zone between strikers and their employers. Other times, the Guard was explicitly charged with breaking the strike. During these instances, violence often erupted between strikers and soldiers with terrible, bloody results.

National Guard soldiers clashed with strikers in Buffalo, N.Y., Birmingham, Ala., Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, Salt Lake City and Telluride, Colo., at the turn of the 20th century. In just two years, between 1911 and 1913, the militia was mobilized against coal miners in West Virginia, textile workers in Massachusetts, textile workers in New Jersey, and copper miners in Michigan. During an infamous bloodbath in 1914, soldiers killed striking coal miners and their families in Ludlow, Colo., including at least six men, two women and 12 children.

During the 1934 Auto-Lite strike in Toledo, a battle raged for five days between 6,000 strikers and 1,300 members of the Ohio National Guard, leaving two strikers dead and more than 200 injured. Three years later, during the famous occupation of General Motors in Flint, Mich., the governor ordered thousands of soldiers to the factory, as the workers swore to resist them by force.

And in Wisconsin, Gov. Albert Schmedeman used the National Guard to disrupt a 1933 strike by dairy farmers, sometimes with bayonets and tear gas, when they tried to raise the price of milk. Newspapers reported that he was preparing for a "bona fide war." The Guard mobilized again the next year during a strike by the United Auto Workers. It was the last time the National Guard would be used during a strike in Wisconsin. Until, possibly, now.

The use of the National Guard against workers is supposed to be a relic of the past, nearly unimaginable to us. That's because of an uneasy understanding, evolved over time, between citizens and the state over the use of state force against civilians. In her excellent book "Army Surveillance in America, 1775-1980," historian Joan Jensen argued that this understanding "maintained restraint, sometimes precariously, in using the army to defend the government from the domestic population."

In other words, Jensen argues that the concept of voluntary restraint by the executive branch -- as opposed to codified legal restraint -- is still largely the governing principle at work when deciding whether to mobilize a domestic military force. So Gov. Walker's action is significant because it is an expanded interpretation of the power of the executive office. This would introduce once again the idea that a governor could use the military to impose his personal, political will on a state.

The cultural and historical significance of Gov. Walker's action can't be ignored. When he proposes using the National Guard to break a strike, he conjures a period of American history in which labor and capital were locked in violent, terrible struggle, when income inequality had reached epic heights, and workers had to bleed to organize. This is a step backward, not forward, in the march of American progress.

Stephanie Taylor is a co-founder of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, and a doctoral candidate in American history at Georgetown. Her research focuses on the relationship of labor and the state in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.

Shares