It remains to be seen whether Scott Walker, the Wisconsin governor bidding to deny public workers collective bargaining rights, has taken things one step too far, but it's clear that today's Republican leaders -- and an increasing number of Democrats, too -- welcome the opportunity to wage battle with public employees and their unions.

From the standpoint of political strategy, it's hard to argue with their logic. Fair or not, the perception has taken hold that public sector workers have become a privileged class -- showered with generous benefits and treated to favorable work rules by politicians who fear saying "no" to them, even as their private sector counterparts make painful sacrifices. Thus, New York's Democratic governor, Andrew Cuomo, is demanding major concessions from public employees just as aggressively as Republican Chris Christie is in New Jersey -- and both are faring quite well in polls. And Walker's basic proposal for union givebacks is popular in Wisconsin.

What Cuomo, Christie and others are profiting from is a divide among working- and middle class Americans. To those who don't enjoy them, the pension and healthcare benefits that many public workers have negotiated are just as likely to be a source of resentment as aspiration. And when economic conditions are as grim as they are now, this resentment is particularly pronounced -- and, from the politician's standpoint, easy to manipulate.

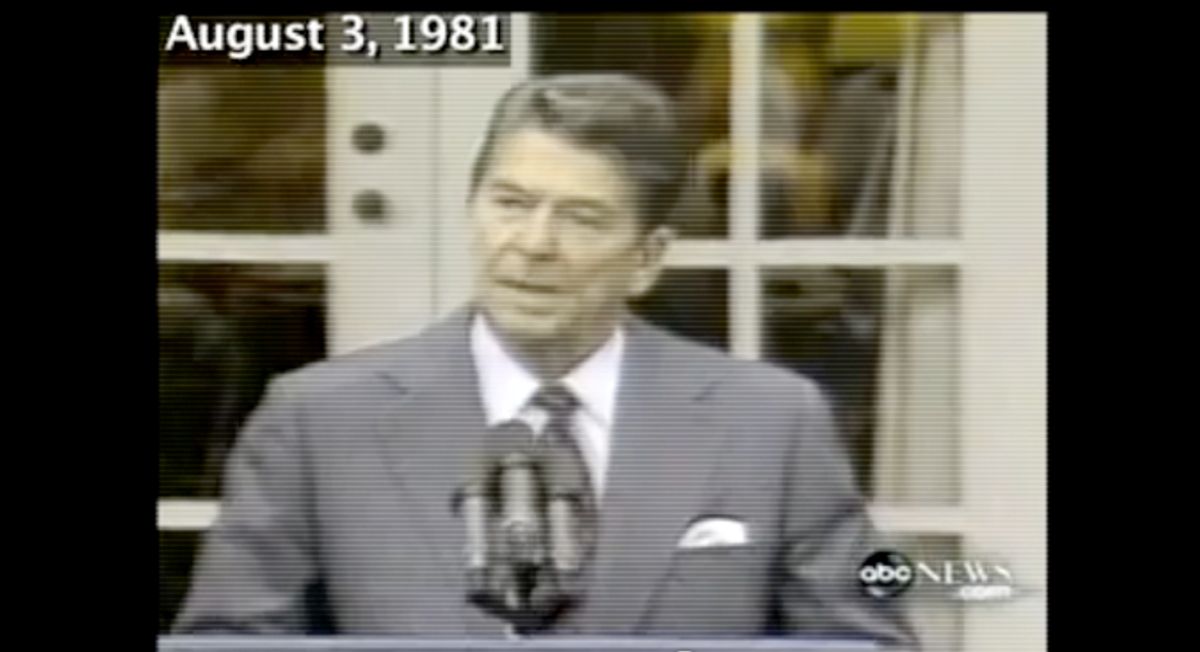

It's a lesson that was first delivered -- emphatically and memorably -- 30 years ago, when Ronald Reagan called the bluff of 11,400 striking air traffic controllers, fired them, dissolved their union and banned them from ever getting their jobs back. He was called petty, vindictive and cruel, but you wouldn't have known it from the polls: Firing the air traffic controllers was one of the most popular episodes of Reagan's presidency. The saga, which played out just as the economy -- already plagued by stubbornly high inflation, unemployment and interest rates -- was plunging into a deep recession, demonstrated just how easy a divide-and-conquer approach to union politics could be.

When Reagan came to office, members of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) thought they had caught a break. Since its creation in 1968, PATCO had been something of a loner in the union world. In the 1980 presidential campaign, it had actually endorsed Reagan, who pledged to address the controllers' longstanding grievances about long hours, dated equipment and generally stressful work conditions.

But when it came time to negotiate, PATCO members were sorely disappointed. Essentially, they asked for a reduction of their schedules to 32 hours per week, the ability to retire with full benefits after 20 years, and a raise of $10,000 for every controller. Forty-hour weeks, they claimed, were too onerous and could lead to danger in the skies, while 20 years of daily work as a controller was enough to burn anyone out for life. The price tag for their wish list was around $500 million -- or about $460 million more than Reagan was willing to shell out. Instead, the administration offered 42 hours of pay for 40 hours of work, paid retraining for workers with medical issues relating to their work, and a chance for controllers to earn more than the annual wage limit by working nights, weekends and holidays. The negotiations were ugly and a strike was threatened, but at the end of June 1981, PATCO President Robert Poli pronounced the deal "fair" and recommended it to his members.

Within weeks, though, the deal collapsed, with PATCO members rejecting it by a 95 to 5 percent ratio. The two sides returned to the table, but their differences were so vast that talks quickly dissolved.

"At a time when President Reagan and Congress are working strenuously to control federal spending and reduce inflation," Drew Lewis, Reagan's Transportation secretary explained, "we cannot yield to demands that would contradict all our best efforts for reasonable and sensible fiscal policy."

So it was that PATCO members voted to strike and, at 7 a.m. local time on Monday, Aug. 3, the vast majority of them walked off the job. Their willingness to reject the deal Poli had made and their eagerness to strike was a product of supreme confidence. Their skills were highly specialized, so they'd be hard to replace. Plus, their brothers and sisters in the pilots union and the airline mechanics union -- to say nothing of their fellow controllers overseas -- would surely stand with them in solidarity. Millions of Americans depended on air travel. Surely, the president would quickly come back to them with a better offer.

They maintained this confidence even when Reagan responded that same day by citing the Taft-Hartley Act, which forbade strikes by public employees, and announcing:

It is for this reason that I must tell those who failed to report for duty this morning that they are in violation in the law and that if they do not report for work within 48 hours they have forfeited their jobs and will be terminated.

But no president had ever followed through on a threat to fire striking public workers. Even Richard Nixon, who'd flirted with doing so during a postal strike 10 years earlier, had made sure to establish back-channel talks with labor leaders that ultimately settled the strike. The controllers assumed Reagan was playing the same game.

"If we're all fired," Poli said, "I want to know who's going to work the airplanes."

Said the president of PATCO's Omaha chapter: "He's bluffing."

But PATCO's leverage quickly took a hit, when organized labor leaders met in Chicago to discuss how to handle the strike. The pilots and mechanics unions could have opted to honor the picket line, a move that would have shut down the airline industry on the spot -- and, perhaps, forced Reagan's hand. William Winpisinger, the head of the mechanics union, urged this course, but his members rebuffed him. The pilots felt the same way. They would all continue working. When Reagan's deadline arrived, the controllers stayed home -- and were promptly fired. It was the largest mass dismissal of federal workers in U.S. history.

PATCO's hopes then rested with the court of public opinion. Maybe the strike would cause so many flight cancellations and prompt so many Americans to cancel their travel plans that the administration would be forced off of its hard-line stance. Again, though, the controllers were frustrated. First, the pilots union publicly vouched for the safety of the administration's emergency arrangements – 60-hour workweeks for the controllers who hadn't walked off the job and for the military personnel who now joined them, and a plan to begin hiring and training thousands of new controllers immediately. Air traffic was lighter than usual the first week of the strike, but the decline wasn't nearly as significant as PATCO had warned. The major carriers lost about $25 million for the first week, not the $100 million that had been forecast. And in the following weeks, traffic picked up and those losses declined.

It quickly became apparent that the public was behind Reagan. A mid-August poll found that 64 percent of Americans supported the firings. Nearly 70 percent believed the union had acted irresponsibly by striking. And more than 60 percent expressed confidence in the federal government's ability to oversee air traffic without the strikers. The administration announced in late September that it was accepting applications for new controllers -- 125,000 people applied, and the first class of 900 prospective controllers was quickly sent off to training school in Oklahoma. Even among those who belonged to unions, there wasn't an outpouring of sympathy for the controllers.

"Sure, they have a right to strike,'' a Chicago cop told the New York Times, ''and they have a right to get fired, too. I can't feel sorry for them. Reagan has to draw the line somewhere. If other federal employees see him back down, they'll figure they can strike and get away with it."

By the end of October, the Federal Labor Relations Board agreed to decertify PATCO. Appeals in federal court failed. Poli quit shortly thereafter. The union had been killed. There were then calls for Reagan, having delivered his message, to hire back some of the strikers, in the interest of improving safety and efficiency in the skies. But to Reagan, there was no point in doing this. His stand against PATCO was popular, even with blue-collar voters. Why show mercy now?

Plenty of union members, of course, were enraged by Reagan's actions. And in 1984, as he was winning nearly 60 percent of the national popular vote, just 39 percent of AFL-CIO members voted to reelect the president. But that so many union members and blue-collar Americans supported him during the '81 strike -- enough to keep the pilots and mechanics unions on the sideline, enough that the administration was flooded with applications for the fired controllers' jobs, and enough that the presence of a picket line did almost nothing to curb airline traffic -- was a revelation.

When times are tough and you pick on public sector unions, Reagan showed, it hardly means that the working- and middle class masses will rise up against you. In fact, a good number of them might just rally around you. No wonder Gov. Walker, in an unguarded moment last week, seemed to admit that his collective bargaining push isn't really about balancing Wisconsin's budget, as he's claimed publicly. It's about staging a Ronald Reagan moment of his own.

Shares