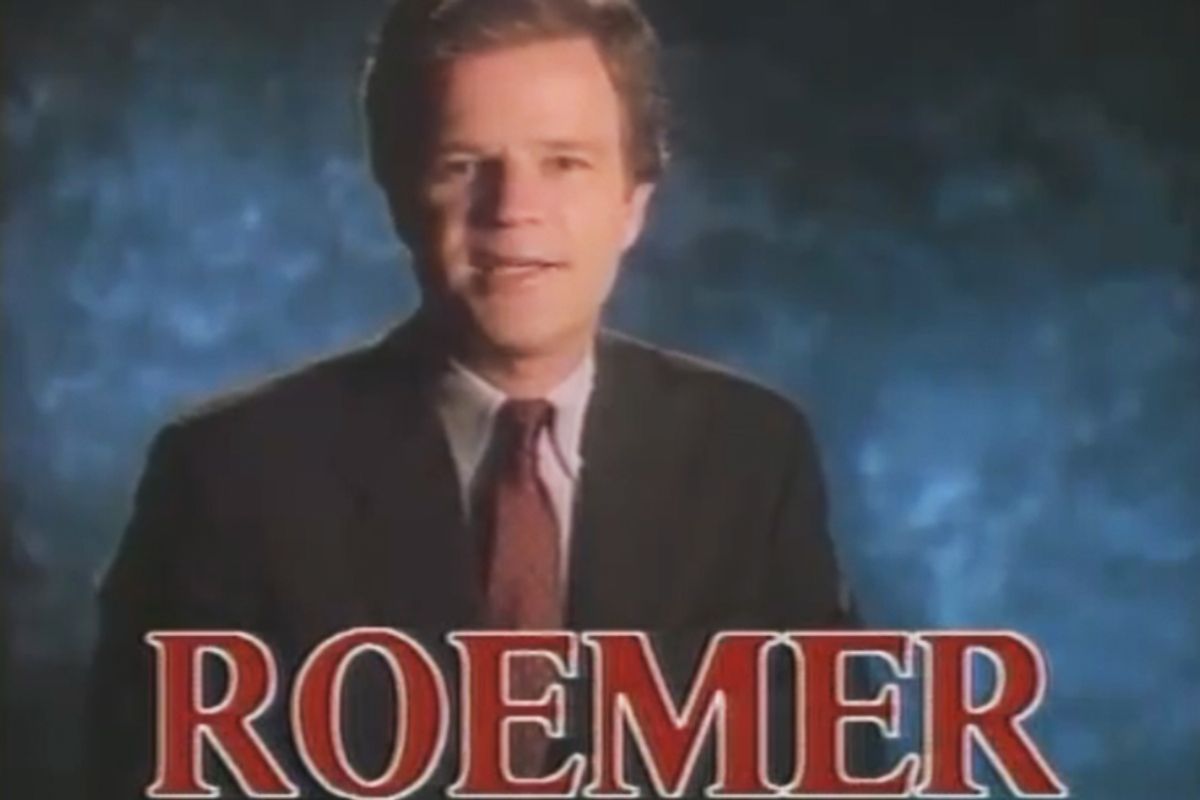

There's a new entrant into the Republican presidential sweepstakes, and you can consider yourself excused if his name doesn't mean much to you. Buddy Roemer is 67 years old, hasn't won an election in 23 years, hasn't been in office for 19, and hasn't stood on his own on the political stage in 16.

But his pending candidacy (he's due to form an exploratory committee on Thursday) is a perfect illustration of how weak the competition for next year's GOP nomination now is.

Roemer, to the extent he's remembered at all outside of his home state, is best known for managing to win just 27 percent as the incumbent in Louisiana's 1991 preliminary gubernatorial election -- even though one of his two main opponents was the ex-Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan and the other was enjoying a break between indictments on federal corruption charges.

That campaign began with immense promise for the highly ambitious Roemer, who had been elected governor in 1987 as a conservative "Boll Weevil" Democrat -- only to switch parties in early '91. The road map seemed simple: He'd win a second term as a Republican, then begin positioning himself as the South's candidate for the 1996 GOP presidential nomination.

The national Republican Party -- led by George H.W. Bush's White House -- embraced Roemer's switch, for good reason. Like the rest of the South, Louisiana's politics were shifting, with white voters -- many of whom had inherited an affiliation with the Democratic Party -- increasingly attracted to the national GOP's conservative, Southern-friendly messaging. But there was an art to this messaging. Ever since the debacle of 1964, when the GOP had nominated civil rights opponent Barry Goldwater and suffered one of the worst landslides on record, Republicans had been careful not to engage in blatant racism in their appeals to Dixie, lest they seem like monsters to the rest of the country.

The rise of David Duke, the aforementioned ex-Klansman, in the late 1980s threatened this delicate balance. When Duke ran as a Republican for the Louisiana state Legislature in 1989, he did so as a reformed bigot, swearing off his Klan past and claiming that he now believed in racial equality. And when he won that February '89 election, Bush and other national Republicans rushed to repudiate him. But Duke was on to something. If the national GOP could make inroads with Southern whites by embracing Christian conservatism and railing against affirmative action, welfare and federal power in general, so could he. Duke's past made him poisonous to the Republican Party, but his platform was essentially the same as the GOP's. He then ran for the U.S. Senate in 1990, and even with the Bush White House disavowing him, managed 44 percent of the vote against Democratic incumbent J. Bennett Johnston -- a shocking total, given Bennett's seeming popularity and the fact that Duke had only been polling in the teens.

Emboldened, Duke set out to run for governor in 1991, and national Republicans began panicking that they might not be able to stop him. It was in this context that the Bush White House began courting Roemer. His mandate in his first campaign in '87 had been nonexistent; he'd finished first in the preliminary election with just 32 percent of the vote, then defaulted into the governorship when Edwin Edwards, the Democratic incumbent who had beaten corruption charges during his term, declined to contest the runoff. Instead, Edwards set about undermining his successor and positioning himself for a comeback bid in '91. Roemer's first term had been rocky and Edwards was well-positioned to exploit his vulnerabilities on the left, so the governor was quite receptive to the White House's entreaties. We'll raise money for you and make sure no other Republicans run, Roemer was told, which should guarantee that you'll make the runoff -- in which you'll have no trouble beating Edwards or Duke in a one-on-one race.

For Roemer, this plan had the added benefit of enhancing his national prospects. The rise of an authentically Southern Republican presidential candidate seemed inevitable. The White House was offering him a chance to switch with significant political cover. He could win in '91, then serve out his term and fulfill his national aspirations by running for president in 1996 (when the GOP nomination would be open no matter what happened to Bush in the '92 campaign). So it was that Roemer announced his switch in March '91.

But almost immediately, it became clear that the White House wouldn't be of much use to Roemer. Bush and his allies helped Roemer raise money and Vice President Dan Quayle was even dispatched to campaign with him, but Louisiana Republicans reacted with resentment. Clyde Holloway, a staunchly pro-life Republican congressman, ignored the White House's threats and entered the race -- and promptly won the state party's official endorsement. And Duke, defying predictions that Roemer's party switch might make him think twice about running, plowed ahead and watched his support grow. By the end, Roemer didn't have a chance. Edwards, rallying the Democratic base of black voters and blue-collar Cajuns, finished first with 34 percent. Duke was right behind him with 32 percent. Roemer, in third place with 27 percent, was eliminated on the spot.

"It's my worst nightmare for the state of Louisiana," Roemer declared.

It was also the end of his national ambitions, at least for the next two decades. Edwards, whose runoff campaign spawned a famous bumper sticker reading "Vote for the crook -- it's important," went on to defeat Duke handily and to reclaim the governorship -- which, after more corruption trouble (he ultimately landed in prison this time), he gave up in 1995. Roemer made a comeback attempt that year, but was thwarted by Mike Foster, an extremely conservative ex-Democrat (who would end up endorsing Pat Buchanan in the 1996 GOP primaries --helping "Pitchfork Pat" score an early, momentum-generating victory over Phil Gramm in Louisiana's caucuses).

When it began, the 1991 Louisiana gubernatorial campaign was supposed to be a springboard to national glory for Buddy Roemer. Instead, it derailed his once-promising career. And now, as he heads off to Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina, it makes a nice reference point for commentators who see the 2012 Republican field as heavy on B- and C-list talent: Mitt Romney is such a weak front-runner that even the guy who lost to David Duke thinks he can beat him.

Shares