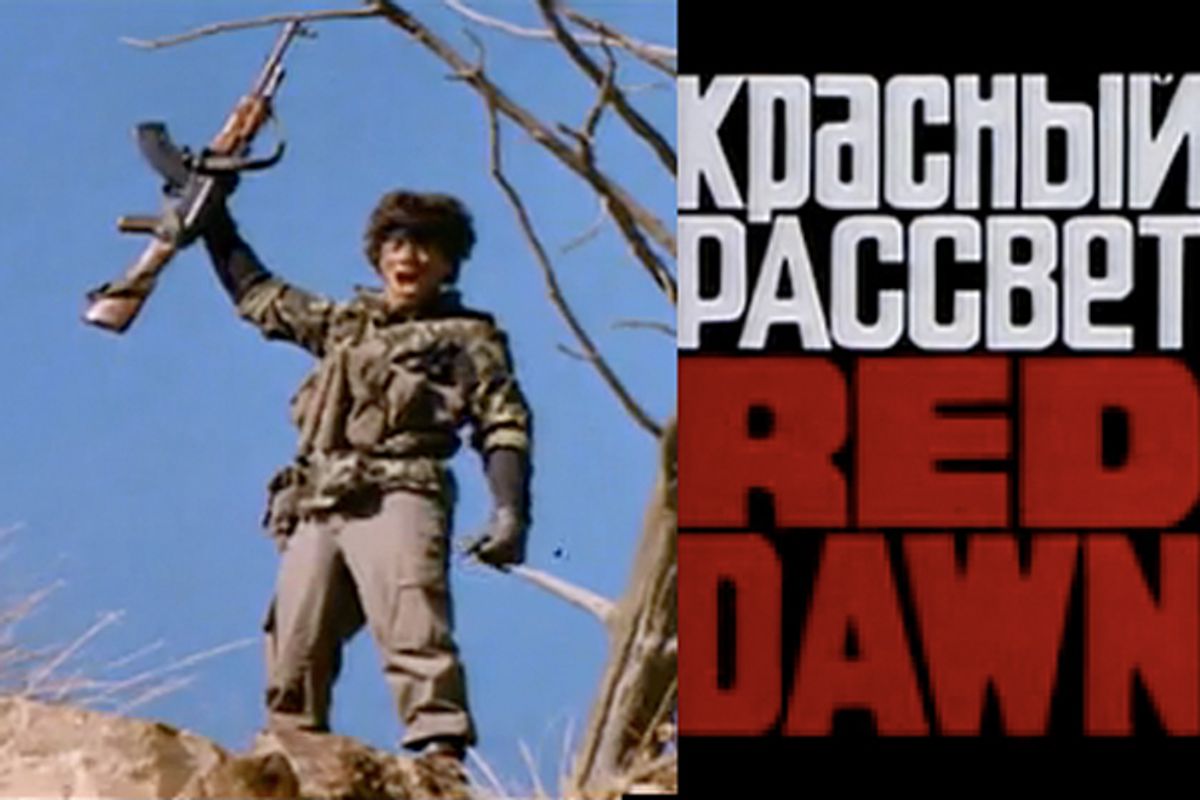

The 1984 film "Red Dawn" fantasized about a group of American teenagers called the Wolverines who valiantly repelled an invasion of foreign communists. For its mix of dystopia and hope, the movie became such an enduring cultural touchstone that U.S. military leaders honored it by naming their 2003 effort to apprehend Saddam Hussein "Operation Red Dawn." Amid the triumphalism, however, we missed the fact that the invaders started winning -- a fact that none other than "Red Dawn's" 2011 remake underscores.

That's the subtext of a Los Angeles Times report this week about MGM taking "the extraordinary step" of digitally removing fictional Chinese villains from the $60 million film "lest the leadership in Beijing be offended." Why the fear of upsetting such an odiously anti-democratic government? Because movie executives worry that a film involving a negative message about China "would harm their ability to do business with the rising Asian superpower, one of the fastest-growing and potentially most lucrative markets for American movies."

The studio suits are right to be concerned. China's government only allows about 20 non-Chinese movies per year into its theaters, and in the late 1990s, the regime halted Walt Disney, Sony and MGM business in the country after those companies produced films deemed critical of China. Seeking to avoid a similar fate, the film industry now regularly shapes its products to appease -- rather than challenge -- the political agenda of the Chinese despots. In that sense, the only thing newsworthy about this week’s "Red Dawn" tiff is the public nature of the content revision.

Whether you are a "Red Dawn" fan or not, the episode shows that for all the high-minded theories about American cultural exports aiding democratic ferment and challenging autocracy, the dynamic is starting to work the other way as autocracy gives orders to American culture. Indeed, wielding its increasing market leverage, China is now countering our First Amendment ethos with a push for what Times reporter Ben Fritz calls pervasive "self-censorship” -- the kind in which America's media industries preemptively shape content to keep China's dictators happy.

The consequences are more profound and worrisome than just a change of bad guys in a campy '80s retread. Just ask Rupert Murdoch. In 1993, the world's leading media baron removed the BBC from his Star TV channel so as to satisfy Beijing and thus secure the station’s access to China's audience. A few years later, Murdoch's publishing firm nixed a book by British diplomat Christopher Patten after seeing that the manuscript was critical of the Chinese government, and then the same publishing company released a fawning biography of Premier Deng Xiaoping by the dictator's daughter.

Then came Google’s move in 2006 to censor its search engine in exchange for a pass through China’s Great Firewall. And though Google recently said it was ending that censorship, Microsoft's Bill Gates -- another powerful content gatekeeper with business interests in China -- publicly slammed companies for daring to thwart Beijing's demands.

In a radio interview this week, Fritz explained the cumulative effect:

"If you think the rules and restrictions of the authoritarian government in China are a bad thing and amount to censorship, then in a global economy where products made in America are seen and consumed in China, those rules and that censorship is affecting what we here in America see."

And unfortunately, no band of Wolverines can stop it.

Shares