This piece originally appeared on New Deal 2.0.

The annual drop-dead moment when Americans must file tax returns or face unpleasant consequences has become an opportunity for the Tea Party, protesting what it sees as crippling taxation and overactive federal government, to rally its supporters. Extending this year's filing deadline from April 15 to today, April 18, the IRS gave Tea Partiers a big weekend, and all over the country, tax-day events hymned unregulated markets, excoriated federal programs like the health-insurance reform bill, and defended anti-labor governors. Anti-Obama leaders from Sarah Palin to Donald Trump urged the faithful to oppose evils summed up for them in the annual requirement to file federal tax returns. For the Tea Party, "Tax Day" represents all that's gone wrong with America since the founding.

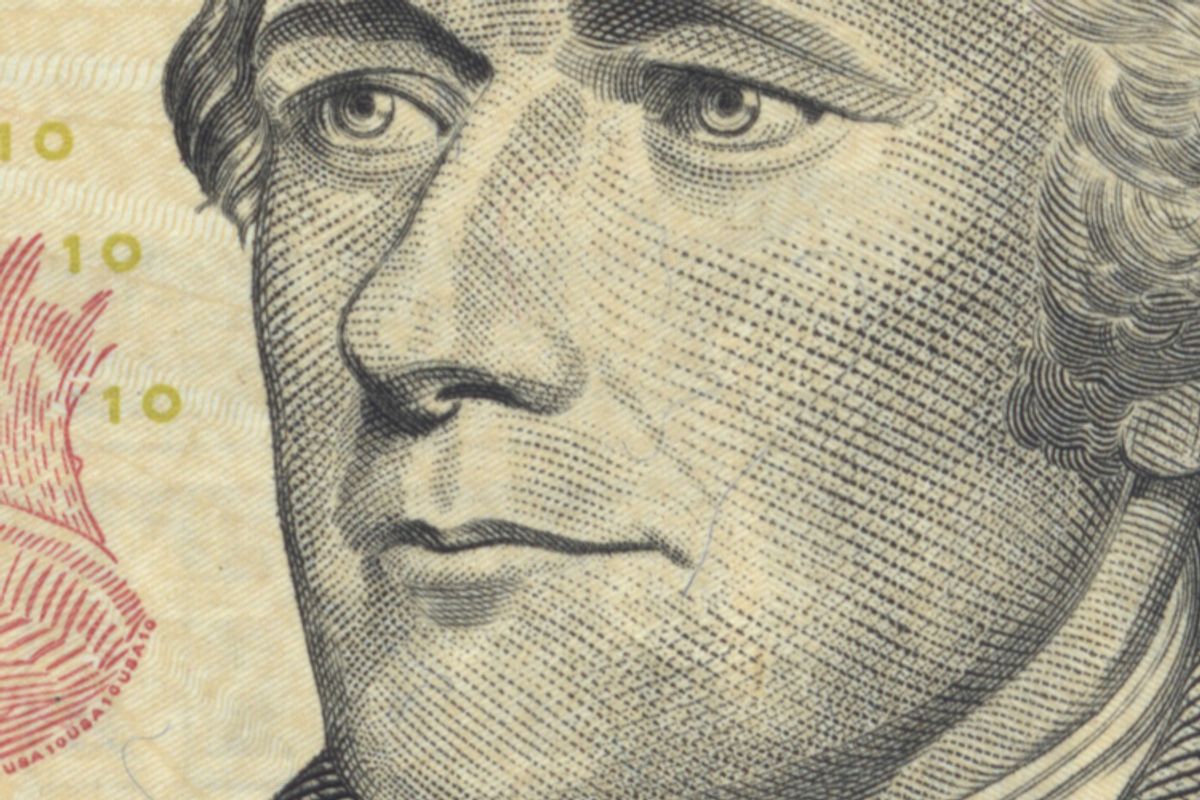

So as we stand on long lines at the post office hoping to avoid the midnight axe, we might spare a moment to consider the father of federal taxes, Alexander Hamilton. Our first Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton is celebrated by both establishment liberals and establishment conservatives: The Hamilton Project is an economic effort of the liberal Brookings Institution, and former Obama budget director Peter Orszag hung a Hamilton portrait in his office; on the right, the writer David Brooks and former Bush Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson are two of Hamilton's biggest fans. It's not surprising. Hamilton is rightly said to have put the new nation on sound financial footing and secured its creditworthiness. He gave us our first comprehensive national finance policy.

That policy depended on exercising certain economic powers that finance nationalists like Hamilton and his mentor the rich financier Robert Morris, as well as planter nationalists like James Madison, had been striving to achieve for the federal government throughout the 1780's, and which came to fruition at the Constitutional convention in 1787. While Hamilton and Madison would arrive at dire odds over whether the Constitution gives the federal government the right to form a central bank (Hamilton yes, Madison no), all nationalists had long agreed that a national government, unlike a confederation of states, would have a right to tax its citizens directly, throughout the states. And unlike what they saw as state governments' susceptibility to the American popular-finance movement's riot and noncompliance, a national government, nationalists hoped, would have both the will and the police resources to enforce and collect taxes.

So whereas Tea Partiers sometimes associate their objections to federal taxes with a desire to "get back to the Constitution," federal taxation is one of the Constitution's central purposes. And we can thank the wunderkind Alexander Hamilton for proposing the legislation by which the first U.S. Congress imposed the first federal tax ever on an American product.

Hamilton wasn't messing around. Empowered by the new government to do what he and Morris had long been frustrated in trying to do, the young, charismatic, brilliant, diligent Secretary worked up a full-blown plan for connecting national wealth, and even more importantly national credit, to ambitious national aims. Like Morris, though to a far more sophisticated degree, Hamilton wanted the United States to become an economic powerhouse and financial empire to compete with England. And he'd been tireless in figuring out how to do it.

The key, as Morris had always suggested, was to combine a big public debt with vigorously enforced taxes earmarked for funding that debt. That is: sell U.S. bonds to the small, rich merchant lending class and, as Morris had put it, "open the purses of the people," collecting taxes from the American people, in metal, not paper, and earmarking revenues for paying the bondholders their 6% interest in hard, cold cash -- 6% untaxed interest, that is. Federal power would thus shift national wealth upward and consolidate it. Yoking national credit to national interest, government would serve as an economic pivot between the creditors and the people and thus be in a position to finance roads, canals, wars, and other national projects.

Morris had fought hard during the confederation period for a simple federal tariff on imports, known as an "impost," and opposition even to that measure had always been stiff: states wanted to retain their sovereign power to tax. But he'd also schooled his supporters in what a real federal tax slate would look like. Once people had become inured to paying a federal tariff, Morris had predicted, the federal government would be able to impose taxes on domestic products too, taxes known as "excises." Continuing to expand tariffs alone would hit too hard the very people Morris and Hamilton wanted to encourage: the merchant financiers, who also engaged in international trade (that's where they got the gold). Fully consolidating wealth, and fully connecting it to high national aims, meant collecting revenue for finding bonds from people who would never own a bond. Hence the importance, to Hamilton, of imposing domestic taxes.

And Hamilton pulled his whole plan off, pretty much on his own. He is often portrayed as having faced down and tamed a huge public debt that had been run up, somehow, to unfortunate proportions during the war and now needed to be paid off. Nothing could be farther from how Hamilton himself saw the situation. Swelling the public debt had been a project of his and Morris's for many years -- for all the cogent reasons of national credit described above -- and now as Secretary, his plan was hardly to pay the debt down (many of his biographers to the contrary) but to fund it. Which as those of us with credit cards know, is another thing altogether.

In that context, Hamilton further persuaded Congress to assume all the states' debts in the national one, swelling the public debt to the nth degree at last and placing it all in federal hands. That took a tough political fight. Hamilton won it in part because his Madisonian opponents were nowhere near as finance-savvy as he, and partly because empowering the federal government to enact a top-down national finance plan had all along been a chief purpose of the Constitution under which Hamilton acted.

So state debts were nationalized, and a law for funding the domestic public debt was passed. Hamilton couldn't get his bondholders their full 6%, but they were happy enough. Investing in the U.S. looked safe and lucrative.

Funding and assumption: those were Hamilton's great twin achievements, and they did secure the credit of the nation in just the way he and Morris had always wanted. But they depended on a third leg of the finance program, rarely discussed but utterly essential: federal taxation of the American people, with a full-fledged collection service, inexorably spreading federal power to collect, audit, and prosecute throughout the country, from state to state, town to town, and village to village. To Hamilton, taxes weren't an unfortunate necessity. They created a nation, pulling the country together through a network of federal officers opening offices and banging on doors. Running every last detail of that widespread, growing, and powerful federal agency, Hamilton came into his own.

Next week: How Hamilton constructed and calibrated his first federal tax -- the excise on American distilled spirits -- to achieve his and Morris's longstanding goal of quelling the popular finance movement. Also: How the finance populists fought back. In the meantime: Happy Tax Day!

William Hogeland is the author of the narrative histories Declaration and The Whiskey Rebellion and a collection of essays, Inventing American History. He has spoken on unexpected connections between history and politics at the National Archives, the Kansas City Public Library, and various corporate and organization events. He blogs at http://www.williamhogeland.com.

Shares