Andrew Sullivan reacts to the long-form birth certificate:

Nonetheless, I think this should have been done long ago.

Because a president has to put his public responsibilities before his pride and his privacy. That's the price of the job - to defuse or debunk conspiracy theorists or just skeptics with all the relevant information you have.

It's also the job of the media always to press for more information, not less. But so many spent their energy arguing that Obama need do no more and piling on the Birthers. They still seem to think they are gatekeepers, possessors of the power to decide what is or is not legitimate for citizens to ask of their public officials.

Emphasis added. I would tend to agree with the principle of asking for more information not less. But is it really a reasonable standard that the president, or public figures in general (Sullivan clearly has Sarah -- and Trig -- Palin in mind here), should have to "defuse or debunk conspiracy theorists or just skeptics with all the relevant information you have"?

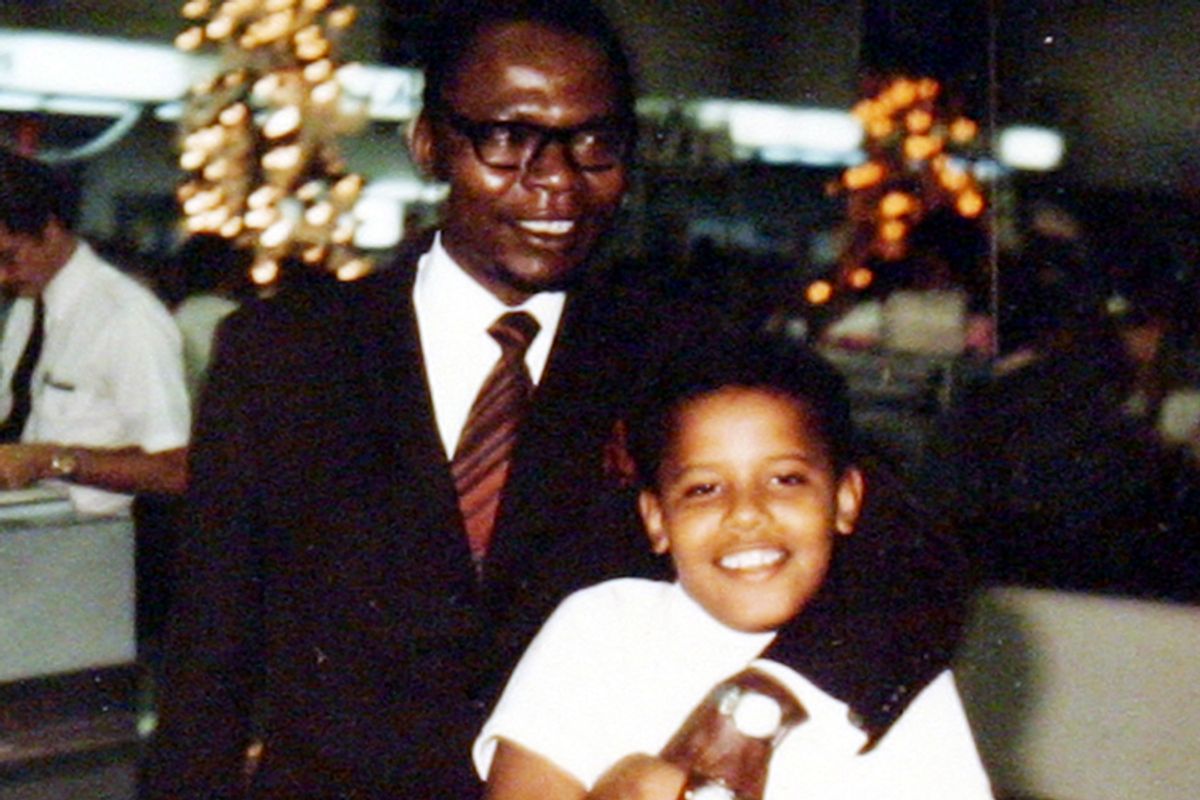

Look at a conspiracy theorist like WorldNetDaily columnist Jack Cashill, author of "Deconstructing Obama: The Life, Loves, and Letters of America's First Postmodern President." Cashill told me in an email exchange today that, despite the birth certificate, he still has doubts about whether the man and woman Obama claims are his parents are actually the president's parents. Here is a sample of Cashill's thinking on the idea that "an American black" -- not Barack Obama Sr. -- is the true father of President Obama:

If a black guy had impregnated Ann, this would explain the family's abrupt departure to Hawaii, the one state in the union where a mixed-race baby could grow up almost unnoticed. It certainly explains the move to Hawaii better than the dreamy rationale Stanley Dunham offers in "Dreams." This scenario makes sense of any number of other details as well, like Ann's angry resistance to the move, her mother's willingness to quit her job as an escrow officer in nearby Bellevue, Wash., Ann's poor performance in her limited first-semester courses at the University of Hawaii, her failure to enroll for the second semester and, most of all, her otherwise inexplicable return to Seattle in August 1961 – if not earlier.

True, to make this scenario work, we have to add one major variable, but it is a credible one. Imagine Ann coming home from class one day in Hawaii in fall 1960 in one of her all-concealing muumuus – she had written friends that muumuus were worn on campus – and telling her father about a charming, larger-than-life Kenyan in her class.

The scheming Stanley befriends Barack Sr. and enlists him in his plot. He explains that a boy named Barack, the legitimate son of a Kenyan, could move through American life more seamlessly than a boy named, say, Stanley, the illegitimate son of an American black.

This is no loonier than the idea pursued by so many -- despite the short-form birth certificate -- that Obama was not born in the U.S. Lest you think it's an entirely fringe proposition, note that Cashill's book, -- which came out back in February -- is #573 in Amazon's rankings of bestsellers. It's #26 in the Politics section.

According to Sullivan's argument, President Obama should be pressured by the media to defuse Cashill's theory. How could he do that? DNA tests of the president and one of his putative Kenyan relatives should do the trick. Why isn't the media insisting Obama take a DNA test to prove he is who he says he is?

This game of demanding "more proof" about basic, well-established facts could go on and on with Obama (Bill Ayers wrote his memoir!) and other political figures (Trig is not Sarah's child!). It's simply impractical and a poor use of resources for the media to demand absolute "proof" to debunk every conspiracy theory. Journalists should investigate these questions -- as they have in all the cases I just mentioned -- and pursue them aggressively if there is evidence of a coverup. But endless appeasement of the conspiracists is not the answer.

Shares