Ulysses S. Grant, the commanding general of the Union Army and the 18th president of the United States, would have been 189 years old last week -- not long after the "official" opening of the Civil War Sesquicentennial, which will run through 2015.

Grant -- like George Washington and Dwight D. Eisenhower -- was both a professional warrior of a defining war and a twice-elected president. And like Washington and Eisenhower he dominated his era, which in his case encompassed both the Civil War and its aftermath, called Reconstruction, from 1862 (when he rocketed to fame with his defeat of Confederate forces at Fort Donelson) to 1876.

At the end of the war, Gen. Grant stood with Republicans in making sure that Union victory was secured on northern terms, restoring the rights and privileges of citizenship to white southerners, but also protecting the rights and establishing the citizenship of the freed people. While president, Grant believed that he was carrying out Abraham Lincoln’s plan of a prosperous reunited country, in the end going further than Lincoln envisioned to ensure black civil rights.

After leaving the presidency, Grant made a triumphal tour of the world from 1877 to 1879, hailed by millions across Europe, India, China and Japan as a military hero and leader of an emerging democratic global power. Retiring to New York City, the ex-president lost his entire savings in a financial scandal and was reduced to poverty. To earn money, he agreed to write about his wartime experiences for Century magazine’s spectacularly successful "Battle and Leaders”" series. Grant's contributions proved so popular that he decided to write his military memoirs, just as he was diagnosed with throat cancer.

While dying of the cancer in 1884 and 1885, Grant completed the writing of his autobiography, which brought renewed reverence from many citizens. The two-volume "Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant" sold 300,000 copies and became a perennial bestseller. Grant's volumes delivered a beautifully rendered narrative of the Civil War written from the viewpoint of the man, after Lincoln, most closely identified with bringing about Northern victory. Although imbued with the spirit of reconciliation between the sections, Grant's account made clear that it was the Northern cause -- union and emancipation -- that would forever remain the morally superior one. The "Personal Memoirs" volumes are considered one of the greatest autobiographies of the English language, earning classic status as both literature and history.

When Grant died on July 23, 1885, he was the most famous of all Americans both at home and abroad. More than a million people watched his funeral procession in New York City on Aug. 8. The dedication of his massive tomb in Manhattan on the 75th anniversary of his birth on April 27, 1897, drew another million plus. Grant’s Tomb, the largest in North America, remained New York City’s most popular tourist site until 1929. Grant’s beautiful memorial sculpture in Washington, D.C., was dedicated on the 100th anniversary of his birth, in 1922. At the foot of Capitol Hill facing down the Mall toward the Lincoln Memorial, the equestrian statue with flanking figures took 20 years to complete and is one of the largest such pieces of artwork in the world.

And yet, despite all of this, Grant’s legacy today is largely forgotten. His memoirs are unread, his monuments are unvisited and in disrepair, and his reputation is synonymous with brutal warfare and overwhelming corruption in public office. In the 1950s, comedian Groucho Marx would pose a standard question to contestants on his quiz show, "Who is buried in Grant’s Tomb?" The answer in 2011 seems to be "Who cares?"

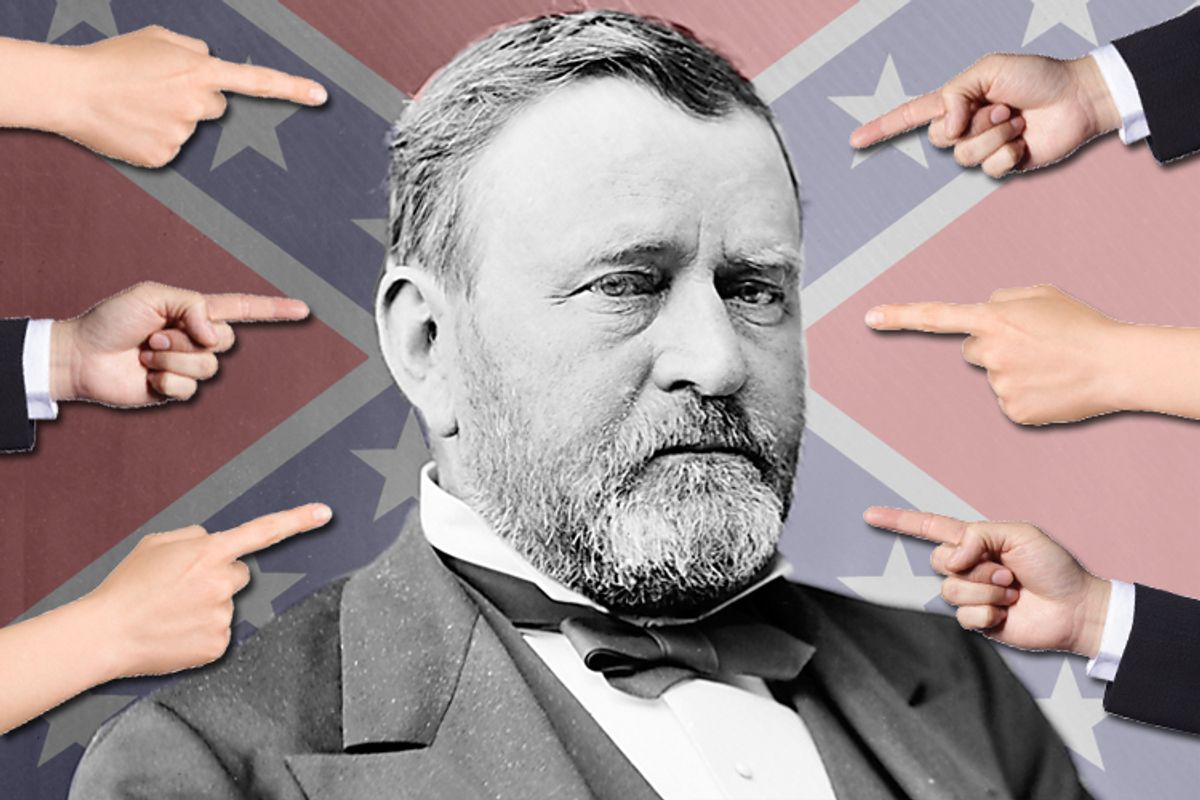

Indeed, few major figures in American history have been so denigrated and disgraced as Grant. How did this happen? A big part of the answer can be found in the successful campaign by historians sympathetic to the Confederacy’s "Lost Cause." Led by William A. Dunning of Columbia University, they portrayed Grant wrongly as only a drunken butcher general and as an enfeebled president who pandered to Radical Republicans, presiding over, as Dunning contended, "the darkest page in the saga of American history." These distortions still thrive in countless history textbooks and classrooms, in movies and on television shows, as well as on popular websites.

Perhaps Grant’s rehabilitation is on the horizon. The 150th anniversary of America’s most devastating conflict will produce a flood of books, articles, exhibits, conferences and the like recasting and reinterpreting the dominant military, social and political events and figures that make up the story of this endlessly fascinating war. Will a serious reconsideration of U.S. Grant, one of the major architects of both victory and reunion, be in the offing? It should be.

One reason mid-19th-century Americans loved Grant was because of his humble background, which proved, like Abraham Lincoln's, that ordinary individuals could rise to extraordinary heights. It should inspire today’s Americans as well. Raised on the Ohio frontier, educated at West Point, veteran of the Mexican War, a hardworking farmer who built his family a log house, Grant was working as a clerk in a leather goods store in Galena, Ill., when he answered President Lincoln’s call for volunteers in that first spring of the American Civil War. Although fame and fortune had thus far eluded this modest man, which has prompted many to label him a prewar failure, he declared firmly and proudly for the Union.

The 39-year-old Grant did not dwell in obscurity for long, gaining fame in Tennessee and Mississippi with a string of victories that included Shiloh, Vicksburg and Chattanooga. He did not rise to his position without controversy. He suffered attacks on his character and generalship. Charges of alcoholism, incompetence and a brutal indifference to death dogged him throughout his career, and affected his reputation after the war as well. Grant did make mistakes. He was caught unprepared for Confederate attacks at Shiloh, and in a deeply regretted order, banned Jews from trading cotton. The historical evidence on his drinking shows that he rarely imbibed and never when it counted. Absorbing all the setbacks and disappointments, Grant displayed great equanimity throughout the war as throughout his life. He accepted the reality of the situation and moved on to the next challenge.

Grant's rare winning record among Union generals secured him a champion in the White House. Promoted to lieutenant general in March of 1864, he took over the strategic direction of the war, achieving victories that guaranteed Lincoln’s election and the end of the conflict. The Union’s hero was praised for the magnanimous terms of surrender he offered to Gen. Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Shortly afterward, he became the first four-star general in U.S. history, remaining as head of the Army until nominated for president by the Republican Party in 1868. Then Grant, aided by newly enfranchised Southern blacks in states reconstructed by Congress, swept to victory with his famous campaign slogan, "Let Us Have Peace."

Once in office, Grant proved to be a stalwart supporter of African-American civil rights, as he was during the war of emancipation. He proudly signed off on the 15th Amendment to the Constitution in 1870, describing the law enabling black suffrage as "a measure of grander importance than any other one act of the kind from the foundation of our free government to the present day." Few current citizens are aware of Grant’s importance in fulfilling emancipation’s promise, even if that promise was not carried out until the next century. Committed to a genuine reunion, he also signed off on a generous amnesty to former Confederates in 1872. Other successes in foreign policy and economic policy marked his first term.

In 1872, Grant, the first president to be reelected since Andrew Jackson, found himself beset by growing scandals, such as the infamous Whiskey Ring. They threatened his administration as did the major depression that struck in 1873. The northern public’s desire to continue unpopular Reconstruction polices waned, and then died. In sum, Grant’s political career proved frustrating and disappointing. Personally honest, Grant presided over an administration that suffered from corruption and bad management.

A few historians have appreciated the difficulties he encountered during his presidency, noting that Grant’s final task harked back to his first one: to ensure a stable transition, this time in the disputed election of 1876. After that, the country reconciled for good.

Perhaps the looming Sesquicentennial will bring many Americans to a more knowledgeable and appreciative judgment of the man. Ulysses S. Grant became the embodiment of the American nation in the decades after the Civil War. No living person symbolized both the hopes and the lost dreams of the war more fully than Grant. No living person more clearly articulated for posterity a powerful truth about the Civil War when he wrote in his "Personal Memoirs" of his feelings about Lee and the soldiers he had led and the slave republic they had defended:

"I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the down fall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse."

Grant's legacy to his own generation was deep and wide, and he became an icon in the historical memory of the war shared by a whole generation of men and women. They believed that an appreciation of Grant could only come with the recognition that he was both the heroic general that saved the Union, and the essential president who made sure that it stayed together

Shares