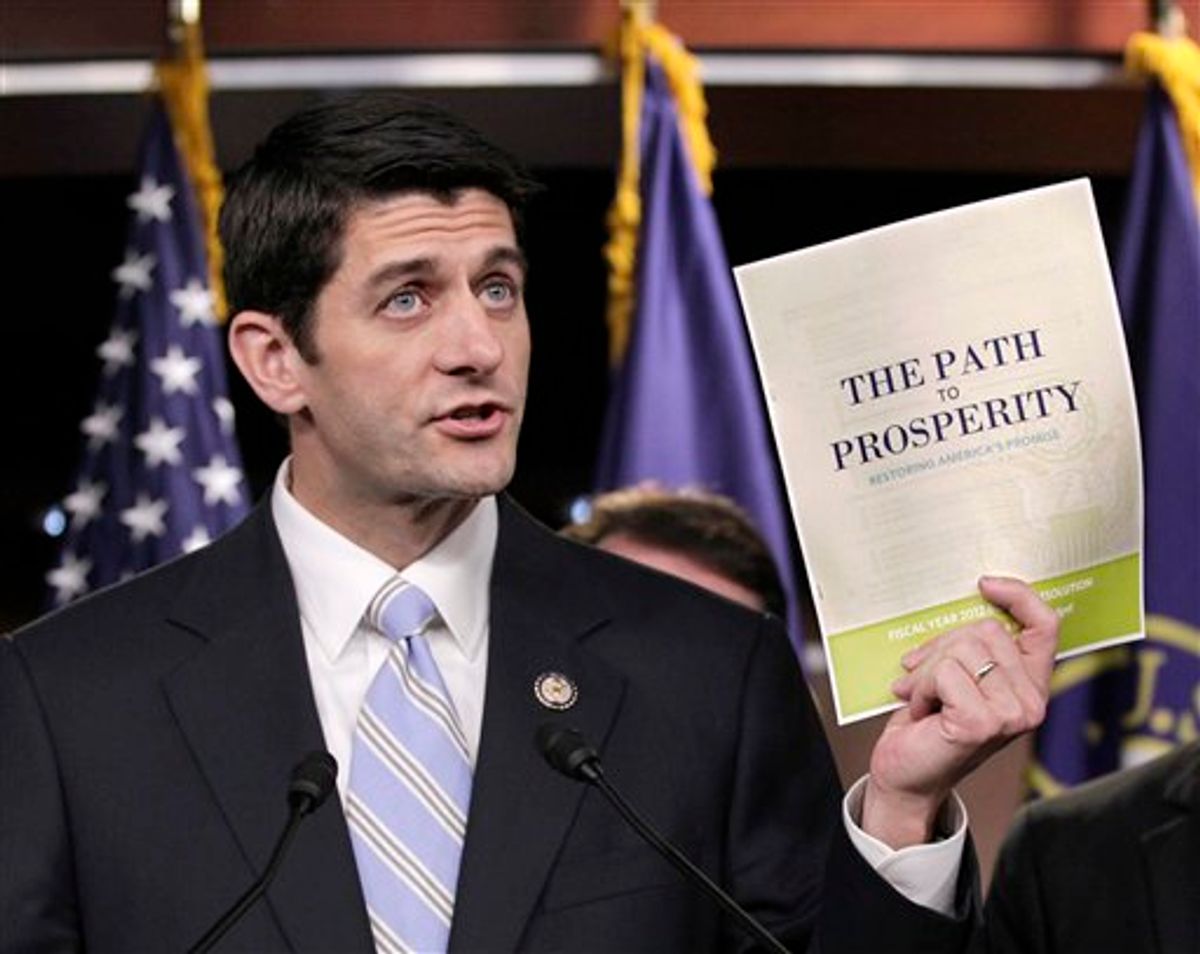

Now that the political toxicity of the Medicare voucher scheme designed by Rep. Paul Ryan and embraced by nearly all of his Republican colleagues in Congress has been confirmed (thanks to last week's special election in Western New York), a number of commentators are urging Democrats not to use the issue as a 2012 campaign weapon.

After all, the thinking goes, at least Ryan and his fellow Republicans are making an honest effort to face up to a serious problem -- wouldn't it be better if, instead of demagoguery, Democrats responded with their own serious plan?

In the New York Times column over the weekend titled "Don't Scorn Paul Ryan," Joe Nocera made precisely this point, arguing that:

…while the Democratic Party might be well served in trying to use the Ryan plan to bury their political opponents, the country itself is not. The debate we need is not about whether Medicare should be reformed, but how.

This echoes a well-publicized comment from Bill Clinton to Ryan when the two men encountered each other backstage at a Pete Peterson Foundation event last week, just after the GOP lost that New York special election. "I hope Democrats don't use this as an excuse to do nothing," the former president was heard saying. By the weekend, numerous commentators were bemoaning the Democrats' eagerness to replicate their special election strategy across the country. "Sadly, the lesson of New York-26 is that Mediscare works," the Washington Post's Ruth Marcus said on "Meet the Press."

But this line of thinking completely misses the point, because it assumes the Ryan plan represents something it doesn't: a good-faith effort by congressional Republicans to start a difficult but necessary dialogue about a third-rail issue. That may be what Ryan believes he's doing, but it's not why top congressional Republicans decided to rally around his plan and make it their official party position. To them, standing for the Ryan budget serves one very important purpose: It establishes vital credibility with the GOP's Tea Party base by intentionally provoking Democrats.

The logic behind this is very simple. As wildly successful as 2010 was for the GOP, there was cause for worry for the GOP establishment, with the party's restive base turning on numerous Republican incumbents and establishment-backed candidates because of perceived ideological impurities. It didn't matter if these establishment Republicans had amassed reliably conservative records (like Utah Sen. Bob Bennett), or if they were uniquely well-positioned to win the general election (like Mike Castle in Delaware), or if the Tea Party-aligned alternative figured to have serious November liabilities (like Sharron Angle in Nevada); the GOP's Tea Party essentially declared two wars -- one against President Obama and the Democrats, the other against Republicans who didn't adhere to a rigidly conservative ideology.

This posed a particular challenge for Boehner when he became speaker, one involving his own political survival. A 20-year House incumbent, his credentials were far more establishment than Tea Party. He happened to be positioned to claim the speaker's gavel when the GOP scored its midterm landslide, but his grip on it would be tenuous. The Tea Party base would be on the lookout for any sign that he was about to sell them out on any issue -- and Eric Cantor, the No. 2 House Republican, and his younger, intensely conservative allies ready to pounce if they perceived an opening to dethrone Boehner.

So what better way to convince the Tea Party crowd that he really was their friend -- and that he wouldn't be one of those deal-cutting GOP compromisers they'd come to hate -- than to embrace Ryan's plan to slash taxes and voucherize Medicare? The fact that Democrats would universally condemn Republicans for supporting this -- and that the media would question Boehner's sanity for making his members vote on it -- would send a loud, clear and unmistakable signal to true believers on the right that Boehner really was on their side. It would buy him the credibility he desperately needed to shore up his own position.

Of course, Boehner had to recognize that the plan was totally symbolic and that, outside of the GOP base, the politics of it would all work against Republicans. But that's precisely the point. Never before have the demands of the Republican base been so insistent and so totally at odds with the party's general election imperatives.

This reality also explains why nearly every Republican in the House voted for Ryan's plan. Many of them are simply true believers who see the plan as a positive and necessary step -- and many of these true believers don't have to worry about general election blowback because they represent overwhelmingly Republican districts where there's no such thing as too conservative. Ryan, as best I can tell, falls into this category.

But there are plenty of House Republicans who do not come from safe districts and who surely understood the perils of supporting a Medicare voucher scheme. Why did just about all of them vote "yes" too? Because they had no choice; the threat of a primary challenge is just too real for Republicans these days. A "no" vote on Ryan's budget, it was clear, had the potential to be to 2012 what as "yes" vote on TARP was to 2010. The Ryan plan gives them something big and real to show conservative activists in their districts, proof that they were willing to take serious heat from the Democrats and the media for standing up for conservative principles.

The key point here is that Boehner and Republican leaders were actually banking on loud, universal and sustained rejection from Democrats (and skepticism from the media) to give them credibility with their own base. They weren't looking to start a serious dialogue on a serious issue; they were looking for a fight. This isn't to say they wanted to hurt their standing with swing voters for 2012. But they were trying to balance two political imperatives -- tending to the base and marketing themselves to general election voters -- that are fundamentally at odds with each other right now. The solution they came up with, it seems, was to push the Medicare issue early in the congressional term, get all of the politically damaging abuse from Democrats and the media out of the way and get the base off their backs, then hope that the whole episode wouldn't mean much to swing voters by November 2012.

In other words, when Democrats attack the Ryan plan, they aren't missing some great opportunity to save Medicare. They're doing exactly what the GOP leadership expected them to do.

Shares