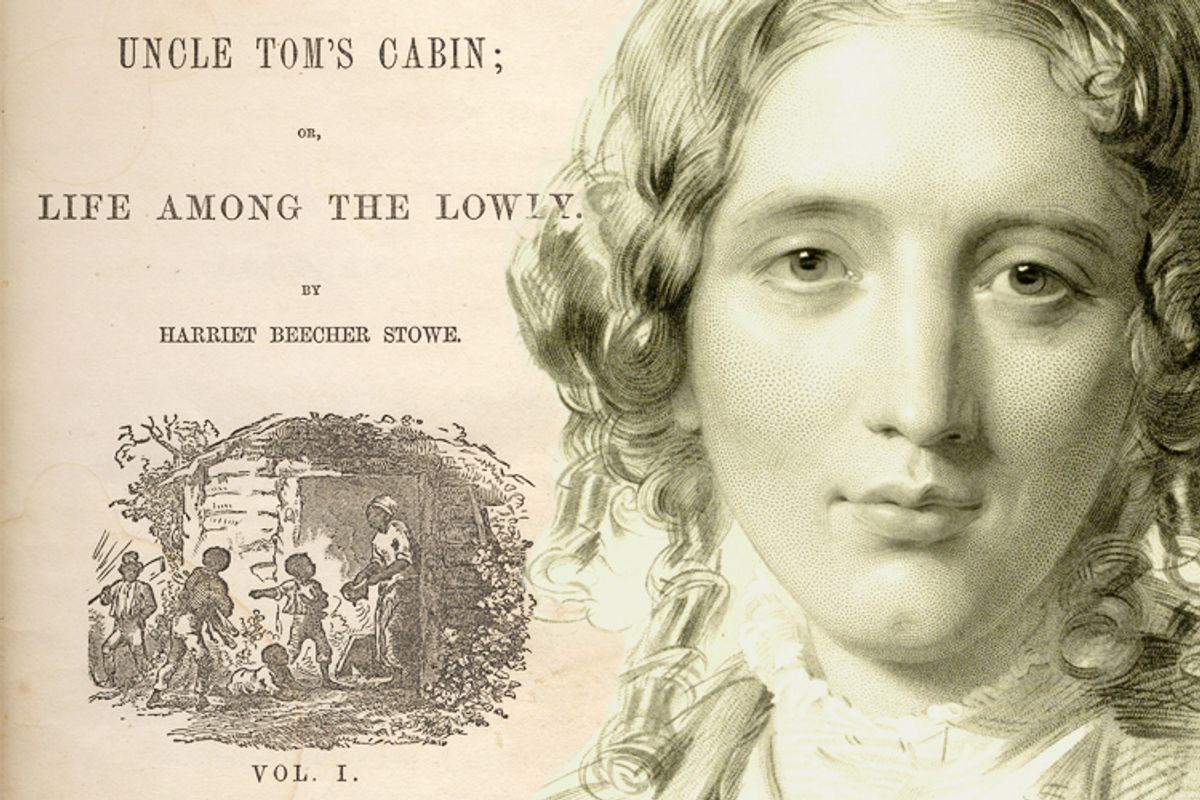

When Harriet Beecher Stowe published "Uncle Tom's Cabin" in 1852, the American slave trade was a thriving institution. The courts condoned it and, as Southerners were quick to claim, so did the Constitution and the Bible. Twelve American presidents had been slave owners, and the abolitionist movement was fragmented and marginal.

But Stowe, a seminal figure in American liberalism, had a knack for making radical concepts palatable to the general public, and her novel became one of the first genuine pop culture phenomena in American history. Within 10 years of its publication, the United States devolved into civil war. And as historian David S. Reynolds argues in "Mightier Than the Sword," a new book that explores Stowe's life and the global impact of her work, it was "Uncle Tom's Cabin" that catalyzed the conflict.

We spoke with Reynolds recently and discussed the enduring significance of "Uncle Tom's Cabin," modern criticism of its use of racial stereotypes, and Stowe's own place in history.

Why was "Uncle Tom's Cabin" so popular?

I'm fascinated by the impact it had. It far outsold any previous American novels, and it was an international sensation. And it was dealing with a very unpopular theme, which was anti-slavery ... [Abolitionist] William Lloyd Garrison was once dragged through the streets of Boston by an angry mob -- this was a very unpopular movement. People wanted to let slavery alone.

But what Harriet Beecher Stowe did was bring [abolitionism] together [with] all these different strands of popular culture -- from religious and temperance writings, to women's writing and domestic literature, to adventure fiction and sensational fiction. She'd never written a novel [before], she'd only written short stories for magazines. But she brought all these elements together and did it in such a passionate, human way.

She said that God wrote the book. She felt that it came through her in a series of visions; she was a very religious person. I think it's just a very moving book, even to this day. Actually, when I taught it -- I don't usually cry over books myself, but when I taught it last fall, I realized just how much sincere personal anguish over slavery went into it, and it actually made me cry.

How did writing your own book change your perceptions of "Uncle Tom's Cabin"? It doesn't sound like you cried the first time you read it.

No, no ... I read Stowe's letters, before she wrote the book. She lost her beloved son Charley to cholera, and [wrote that], "When I lost my son at such an early age, I instantly thought of all the slave mothers in the South, who are losing children daily because they're being sold." She had known many African-Americans personally, in her household and also while living in Ohio, where she participated in the Underground Railroad. So she had this very deep sympathy for slaves, and I could no longer really read her book in a distanced way -- I really felt the emotions, because I knew exactly what had gone into it. She suffered from a variety of illnesses, and they [the Beecher Stowe household] struggled just to stay above the poverty line. I just saw all these challenges that she had, and [how] they mingled with the suffering that she saw in the slaves, and it moved me.

I was struck by what a pivotal figure Stowe really was. In your book, she comes off as a mother of American liberalism.

Yes, in a way she is. She tries to domesticate radical thought -- and this was one reason she was so popular. She tries to appeal to common, everyday feelings of human devotion. These elements can seem sentimental, but they're also universal ... And it was so popular throughout the world that ["Uncle Tom's Cabin"] was actually used for different kinds of causes. It was one of the forces behind the emancipation of the serfs in Russia in 1861, and it was Lenin's favorite childhood book -- he said that it gave him "a charge to last an entire lifetime."

It was the first American book published in China, translated into Chinese. And then it became immensely popular as well through the many plays and adaptations of the novel. It was one of the earliest forms of mass entertainment, in North America and throughout the world -- sometimes, frankly, distorting the [book's message]. It was in the plays, sometimes, that there was a distortion and a stereotypical use of the Uncle Tom figure.

Modern critics fault "Uncle Tom's Cabin" for its simplistic writing style and use of racial stereotypes.

For a long time it was a popular novel among critics -- it was christened the Great American Novel in 1868. Tolstoy loved the novel. Henry James loved the novel. But during the Jim Crow period, particularly during the 1930s when literary criticism in the academy became very conservative, they looked for different things in literature. They didn't want to see social statement or political statement, they wanted to see ambiguity and complexity. Also, they didn't particularly pay attention to literature by popular women writers, so ["Uncle Tom's Cabin"] was kind of dismissed as being sentimental, simplistic. But then in the 1970s and '80s, with the rise of cultural studies and feminist criticism, a lot of critics realized its immense cultural power, [and] realized that a lot of the characters are more complicated than some of the stereotypes would suggest.

I mean, traditionally, most modern readers see it as kind of an old-fashioned and sentimental book, and we think of the Uncle Tom character as being sort of a sellout and a weak, spineless creature. In the book, though, Tom actually reads very strong -- he's in his 40s, he's muscular, he has three children. He's a very compassionate man and Christian man, and he believes in nonresistance. I think the whole record of what happens to the novel [and its reputation] over time really impressed me, because a lot of the people who were once called Uncle Toms -- Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks -- were the victors in the end. In a way, Uncle Tom won. [They were] true to this very firm, nonviolent [form of] protest.

That's a pretty provocative claim. Isn't there some validity to the more modern, critical reading of Uncle Tom's character?

The trouble is that you can't apply today's views on [the time in which] the book appeared. In the South, Harriet Beecher Stowe was [considered] a demonic, satanic lover of African-Americans -- they threw her book in the fire, they imprisoned people who owned it. It was far, far too radical and progressive throughout much of the South. So we can't just call her a limousine liberal or something like that.

Now, there were some militant blacks like James Baldwin, Richard Wright and others who, with the rise of the "New Negro Movement" and the Harlem Renaissance, wanted a more militant voice. And so they used the Uncle Tom stereotype in a negative way. But at the same time we should recognize people like Langston Hughes, who was a great defender of the novel, and he saw how progressive it really was. Alex Haley saw the progressiveness of it. So there is a progressive element [to the book] that certain African-Americans, even in the 20th century, have admired.

Do you think that there's anything that progressives today can learn from Stowe's approach to enacting social change?

"Uncle Tom's Cabin" is a prime example of how [cultural events] can work in an ultimately good way. It galvanized anti-slavery passions in the North, and it also made the South come to its own defense of slavery. So it galvanized those passions, and brought about the war that was very necessary to end slavery.

We live in a much more complicated age. I think that probably ["Uncle Tom's Cabin"] will never be approached in its power. But I still do believe that if somehow political writers could learn how to integrate some of their political views into characters, into characters that we care about in a deep way the way she did, they still could have an effect. I really believe that.

Shares