[UPDATED]

In the summer of 1991, James J. "Whitey" Bulger won the Massachusetts lottery. Well, at least he claimed he did. The $14 million winning ticket was actually held by a South Boston man named Michael Linskey, who had purchased it at the Bulger-owned South Boston Liquor Mart. Linskey then told state lottery officials that he'd actually been partners with Bulger and two others and that they were entitled to half of the jackpot.

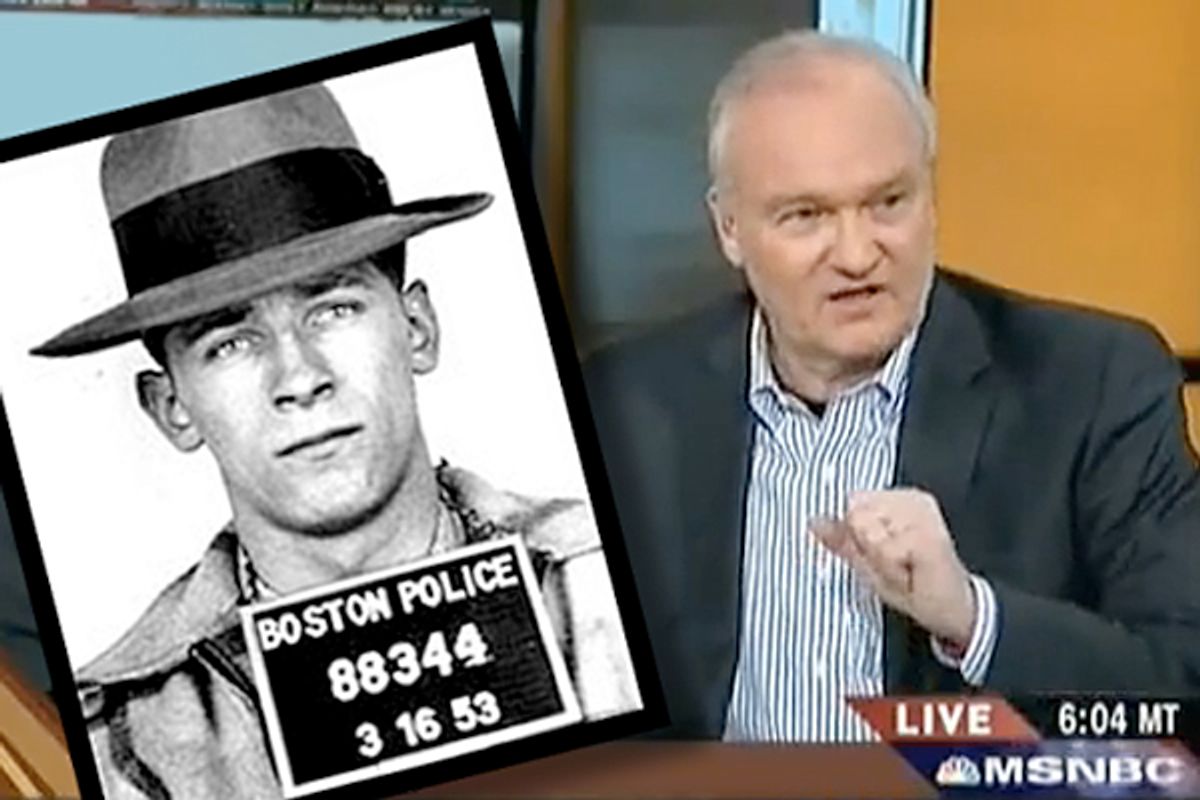

This was all enormously suspicious. It had long been known that Whitey Bulger, whose brother Billy was then the most powerful politician in Massachusetts, lived on the other side of the law, and by '91 it was becoming clear -- and, the closer you looked, glaringly obvious -- that his crimes included racketeering, drug-running and murder. He wasn't just the neighborhood bookie in South Boston. In fact, the only reason he owned the South Boston Liquor Mart was because he'd paid a visit a few years earlier to its previous owner, Stephen "Stippo" Rakes, intimating that Rakes' child might be harmed if he didn't agree to sell the store to Whitey. Similar coercion, just about everyone figured, accounted for Whitey's lottery score.

But not the most influential columnist at the biggest and most influential newspaper in New England. Mike Barnicle took to his Boston Globe column to issue a ringing defense of Whitey -- a man he always called "Jimmy," the name that only the Bulger family used -- and to lash out at anyone who would suggest malfeasance. "Give Whitey a Break" began with this:

In a blatant display of prejudice against local Irish gangsters, some narrow-minded bigots are hinting the Lottery was rigged simply because a friend of Jimmy Bulger's won $ 14 million and split the lucky ticket four ways. Next, in a gross display of piling on, the state treasurer, Joe Malone, said he was disturbed that the guy who sold the winning numbers, my pal, Kevin Weeks, showed up at Lottery headquarters "with a reputed mobster," and I think he meant Bulger.

Barnicle continued:

Hey, good things happen to good people, right? Of course, there is an army of malcontents who refuse to believe that the result of a mere game of chance is on the level when the cash cow moos at the doorstep of a man - Bulger - who, according to illegal eavesdropping by FBI agents and their cheap equipment (And I will show you how lousy their stuff is), runs a vastly overrated criminal enterprise in the area.

And finished with this:

So, lay off Jimmy Bulger. For the first time in his life, he got lucky, legitimately, and won the lottery. Knowing him, he probably already has handed out money to St. Augustine's, figuring that when he goes - and the odds on that are better than winning Mass Millions - there will be some people left behind who will say, "Not a bad guy."

This was the same Jimmy Bulger, of course, who was overseeing a massive criminal operation, one that poisoned the streets with cocaine and other illegal drugs and claimed dozens of lives. Whitey himself had taken part in numerous killings, and his victims weren't all fellow mobsters. When in 1982 Bulger and an associate ambushed and killed Brian Halloran, a fellow gang member, they also took out Michael Donahue, a truck driver who had innocently volunteered to give Halloran a ride home. There was also Deborah Hussey, who had been sexually abused by Bulger's associate, Steven Flemmi, as a teenager. Hussey ended up living with Flemmi, but soon he and Bulger got tired of having her around. And so, according to court documents:

They murdered her in much the same way they murdered their other victims, by luring her into a house and strangling her. Here again, Bulger grabbed Deborah Hussey from behind and scissored her neck between his forearms to crush her windpipe. Hussey fought desperately for her life and knocked Bulger over. When the two fell to the floor, Bulger jack-knifed his body to work his legs around Hussey’s body to crush her torso. The Court infers Hussey lost consciousness from asphyxiation and died within a few minutes.

Granted, these grisly details weren't yet public when Barnicle offered his '91 defense of Whitey. But if they had been, they wouldn't have been shocking to anyone who'd been following the Bulger saga.

Five years earlier, in 1986, the President's Commission on Organized Crime had issued a report that referred to Bulger as "a reputed killer, bank robber, and drug trafficker." And for nearly a decade before that, the Massachusetts State Police and the federal Drug Enforcement Agency had sought to build a case against the man who had seized on the void created by the demise of the New England Mafia and emerged as the region's most powerful, violent and destructive criminal leader. But their efforts had been thwarted over and over again, and only years later -- after Whitey had skipped town for the 16-year flight from justice that ended Wednesday night -- did it become clear why: He'd been protected by rogue FBI agents, who'd essentially functioned as his accomplices.

In other words, to anyone who looked into the matter, it was obvious well before 1991 just what kind of criminal -- and person -- Whitey Bulger really was. And yet, Barnicle continued to treat his readers to an utterly fictitious portrait of Whitey as a generous, kind-hearted, almost lovable protector of his South Boston neighborhood. The summer '91 column was par for the course for him in the late 1980s and early '90s. Drug-running, massive weapons stockpiles, and murders? It was all part of a "myth." Jimmy Bulger, Barnicle would tell his readers, was the real victim, forced to watch his good name dragged through the mud by the unscrupulous media.

Why was he so helpful to Whitey? It probably had to do with his relationship with Billy Bulger, who as the president of the Massachusetts state Senate from 1979 to 1996 wielded enormous power on Beacon Hill. Still furious with the press for its critical coverage of South Boston during the fight over busing in the 1970s (Billy had been an adamant opponent), Bulger tended to treat reporters with contempt, or simply to shun them. But Barnicle cozied up, filing one fawning tribute after another to the misunderstood "Bill Bulger." This was true more than ever in the late '80s and early '90s, when allegations that his law partner had extorted a developer turned Billy into the most unpopular political figure in Massachusetts. But voters in South Boston closed rank around Bulger, and so did Barnicle -- hence the dubious columns about Whitey.

Whitey Bulger went on the lam in January 1995, when his chief FBI protector, a then-retired agent named John Connolly, tipped him off about a pending indictment. Over the next several years, the realities of Bulger's crimes -- and the horrific lengths to which Connolly and others went to shield him -- came to light. But Barnicle kept making excuses. When Whitey was implicated in court for Halloran's murder, for instance, Barnicle swore he was innocent -- but that the judge would never acknowledge this "because he's an arrogant, smarty-pants who is in way over his head here and doesn't know what to do about it." Whitey's drug-running? "That's an interesting question with all sorts of semantic loopholes," Barnicle wrote. In a 1998 column, he asked: "Who had more honor? Bulger or the FBI? The answer is in the wind."

Shortly after that column appeared, Barnicle was forced to leave the Globe after charges of plagiarism and fabrication involving several (non-Bulger-related) columns came to light. But he was quickly back in the game, penning a story for George magazine in February 1999 about the Bulger brothers. It relied on an interview with Kevin Weeks, who had been Whitey's right-hand man and who would later become a cooperating witness. Weeks immediately challenged the piece's accuracy. From a Boston Herald story from Ralph Ranalli:

In the George article, Weeks not only appears to implicate himself in several acts of violence, but he also taunts members of Boston's Italian Mafia - an act numerous underworld observers called fraught with peril despite the Mob's current disarray.

"I haven't survived out here on the street this long by being stupid," Weeks said during a telephone interview. "I'm not going to get up on a soapbox and take on the Mafia. I'm not suicidal."

Beyond the disputed quotes, Weeks charged that the article is riddled with other inaccuracies.

Portraying Whitey Bulger as a dispenser of vigilante justice, Maas and Barnicle recount a story where a "cop's daughter was raped" and her father turned to Bulger "looking for the justice a court couldn't provide." The rapist, the story says, "was never seen or heard from again."

Weeks, however, insisted that the "cop's daughter" was actually a boy, and the son of a Boston Housing Authority janitor.

In another incident recounted by Maas and Barnicle, Bulger stood by as Weeks used plywood sheets to board up a crack house on Silver Street. When the drug dealers complained, Weeks and Bulger "beat them nearly senseless." Weeks acknowledged boarding up the drug house, but said Bulger was not present.

Just before the George story appeared, Barnicle had said that he was hoping to develop a screenplay about the Billy/Whitey story. Herald columnist Peter Gelzinis put two and two together:

In the current issue of George magazine, Mike Barnicle and Peter Maas have formally embarked on their salvage project to restore Whitey to the ranks of gangster-in-good-standing. Or, as Barnicle might say, to give Jimmy back his "integrity."

The article is embarrassingly awful more dreadful, in fact, than Billy's autobiography, "While the Music Lasts." But this is all beside the point. For the article exists only to attract nibbles from Hollywood money men. "The Battle of the Bulgers" is nothing more than the "treatment" of the Billy and Whitey movie Mike Barnicle hopes will take the sting out of his forced retirement from the Globe.

The movie Barnicle envisioned never got made, and when Billy was forced out from his lucrative post as the president of the University of Massachusetts in 2003, the Bulger era of Massachusetts politics came to an end. Billy's demise came after his disastrous appearance before a House committee in 2003 that was looking into the Boston FBI's relationship with organized crime. During his testimony, Bulger seemed defensive and evasive. But while his bitterness toward the press endured into his retirement years, Billy's affection for Barnicle remained. Consider this passage from a 2008 Boston magazine profile:

Suddenly, Bulger lights up. "Oh, Jesus, there's Michael Barnicle!" he exclaims, looking over my shoulder, and it is. Over walks Barnicle, the former Globe columnist, radio host, and occasional sub for Hardball's Chris Matthews on MSNBC, looking a little grubby in an oversize, worn-out T-shirt. Before he was forced to resign from his job at the Globe amid allegations of plagiarism and fabricating sources, Barnicle was derided as an apologist for the Bulger brothers, perhaps the last person in town who still bought the myth of Whitey as a latter-day Robin Hood delivering turkeys to the poor and helping old ladies cross the street. Late last year, he turned up as a member of an investment group weighing an irony-laden purchase of his former paper.

Bulger makes a big show for the room. "Will you put him out of here?" he calls to the laughing waitresses. "Would you please get him out? Do we have anybody here who can get him out? This place is going to hell. This used to be a nice restaurant! I guess I'm going to have to go back to the Four Seasons!" Big laughs. He turns to Barnicle and asks how he is.

"I'm doin' well," Barnicle says. "Same old, same old. Just get up every day and get back in the batter's box."

"You're doing very well," Bulger tells him. "I like your spirit. It's real."

"Well, I like yours, too."

"Bet your life."

Barnicle points out another Globe reporter sitting over in the corner. Bulger nods, then says, "Can you do me a favor? Tell him to get out."

"Wait'll we buy it," Barnicle roars, as he walks away. "We're gonna buy it!"

He may not own the Globe today, but don't worry about Mike Barnicle: He remains a fixture on MSNBC, where his history of plagiarism, fabrications and Bulger hagiography doesn't seem to matter.

UPDATE: Dan Kennedy, a man who knows what he's talking about when it comes to Boston media, has a blog post explaining that the July '91 Barnicle column I cited at the top of this piece is satire. Kennedy notes that the full column (which isn't available on the web) does seem to include an acknowledgement of Bulger's role in "murder and mayhem," albeit one that is couched in "really bad satire, as only Barnicle could write it." Kennedy is right, and I am guilty of not reading the column nearly closely enough.

This doesn't mean that Barnicle didn't consistently use his voice in the 1990s to paint a very misleading image of Whitey Bulger's world. Kennedy notes that "there is no question that Barnicle was and is close to Bill Bulger...and has been an unconscionable apologist for former FBI agent John Connolly, now serving a prison term for his corrupt dealings with Bulger." He also quotes from a 1998 piece he wrote about Barnicle, in which Kennedy argued that "[W]hen it comes to the other Bulger, Whitey, Barnicle crosses the line from irresponsibility into journalistic corruption."

But Kennedy is right: My portrayal of Barnicle's July 1991 column is inaccurate, and I'm sorry -- and embarrassed -- that I screwed it up.

Shares